This spring, Washington lawmakers passed a bipartisan bill to restore voting rights to citizens when they are released from prison. Representative Tarra Simmons (D-Bremerton), who is believed to be the first formerly-incarcerated member of the Washington legislature, authored the bill (HB 1078) , and Representative Jesse Young (R-Gig Harbor) cosponsored. It passed with votes from 83 Democrats and 1 Republican, and Governor Jay Inslee signed it into law in April. It takes effect January 1, 2022.

How it works now

Washingtonians serving time in county jail are allowed to vote. However, those convicted of felonies (including homicide, automobile theft, and DUI) and sentenced to time in state prison are currently disenfranchised until they complete their probation and pay all court-ordered fees and restitutions. Even after completing probation, Washingtonians with felony convictions only have their voting rights provisionally restored. A court, prosecutor, county clerk, or recipient of any restitution being paid has the discretion to revoke the previously convicted person’s voting rights due to any “willful” failure to pay court fees or restitution. Deciding whether a failure to pay is “willful” is up to a judge in each individual case, and the Supreme Court’s failure to sufficiently define the word has led to large discrepancies in punishment for debts across the nation—particularly in cases where debtors are financially unable to pay their fees.

Two court cases, Madison v. Washington in 2006 and Farrakhan v. Gregoire in 2010, challenged the state’s policies of restricting the right to vote based on post-imprisonment fees and of disenfranchising all citizens convicted of felonies, respectively. In both cases, the courts held that the 14th Amendment to the Constitution allows states to take away citizens’ rights to vote. Washington state lawmakers proposed bills in the 2019 and 2020 legislative sessions to change this policy, but they did not make it to a floor vote.

HB 1078 will restore rights, starting in January

In 2021, Washington lawmakers succeeded! This year’s bill was wildly popular with voters—a survey of likely voters showed 87 percent support for reinstating the voting rights of people with felonies upon sentence completion. Public testimony in favor of the bill included representatives of criminal justice and racial equity groups, labor unions, the state associations of county auditors and prosecutors, the Department of Corrections, and organizations supporting voting rights like the Brennan Center for Justice and the ACLU of Washington. The bill’s champions successfully fought off efforts to weaken the bill by opposing a push to exclude those convicted of certain categories of violent crime from re-enfranchisement. Despite strong bipartisan support from voters and bipartisan sponsors, the bill passed along almost-party lines by Democrats in both chambers.

Starting in January, the state will automatically restore voting rights immediately upon release from prison. These rights are not provisional and cannot be removed again, even if a person is re-imprisoned due to probation violations (a misdemeanor). The act also increases the frequency with which the Secretary of State must update the voter rolls to remove people made ineligible due to felony conviction.

Respecting rights of citizens who have rejoined their communities

In 2014, then U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder said:

“Whenever we tell citizens who have paid their debts and rejoined their communities that they are not entitled to take part in the democratic process, we fall short of the bedrock promise – of equal opportunity and equal justice – that has always served as the foundation of our legal system. So it’s time to renew our commitment – here and now – to the notion that the free exercise of our fundamental rights should never be subject to politics, or geography, or the lingering effects of flawed and unjust policies.”

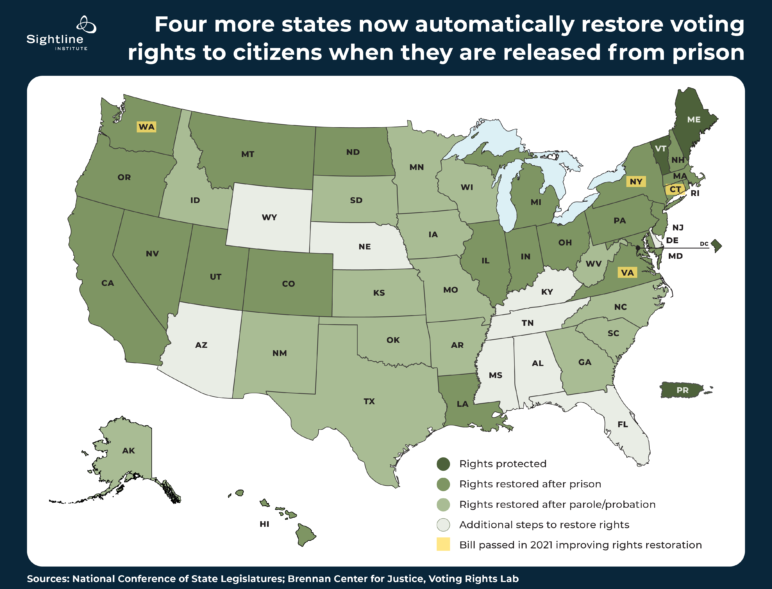

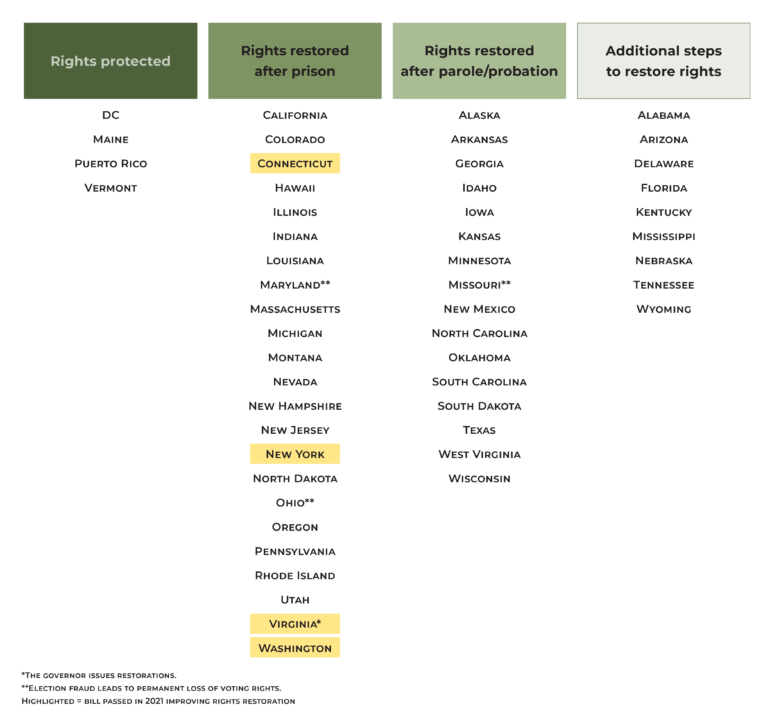

Increasingly, Americans of all stripes and lawmakers, particularly Democrats, agree with former Attorney General Holder. In recent years, states have been moving to restore rights. In 2020, California restored voting rights to people on parole, Iowa restored rights to almost all of those with former felony convictions, and the District of Columbia allowed even currently-incarcerated people to vote.

New York and Connecticut joined Washington this year in passing bills to restore voting rights automatically upon release from prison. Virginia lawmakers passed a bill to amend their state’s constitution to do the same. Disenfranchisement was built into the state’s post-civil war constitution, and amending it will require another vote of the legislature and a vote of the people before it takes effect. In the meantime, Virginia Governor Ralph Northam took executive action to restore the right to vote to all Virginians on probation or parole, mirroring the constitutional amendment, and he has stated his intention of continuing this practice going forward for all Virginians upon their release from prison.

Maine, Vermont, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico allow even currently-incarcerated citizens to vote – and Oregon lawmakers are considering joining them. In 2022, a total of 21 states will restore voting rights to formerly-convicted citizens immediately upon their release from prison. In 17 other states, the formerly convicted are required to complete some or all after-prison terms of their sentence before regaining the right to vote; and another 10 states have a lifetime disenfranchisement policy for some portion of those convicted of a felony. With recent changes in Kentucky and Iowa, no state disenfranchises all people convicted of a felony for their lifetime by default—though some of these policies rest on executive orders, which (as Iowa has shown) are much easier to undo. Sean Morales-Doyle of the Brennan Center noted in testimony that certain states like Alabama and Florida default to lifetime disenfranchisement for some crimes.

Clear standards are better for citizens and for election workers

Clear standards are better for citizens and for election workers

States moving towards automatic re-enfranchisement upon release are finding it’s just easier. Disenfranchising some citizens takes a lot of work. Just ask Texas. There, the policy is to disenfranchise citizens even after they have rejoined the community, but not tell either the citizen or the poll workers about it. Then they wait to see if any people who have already served their time in prison go to vote once released and use public resources to prosecute them and sentence them to more time in prison.

For example, Crystal Mason, a Black Texan, showed up at her polling place and asked the poll workers if she could vote. They gave her a provisional ballot to fill out. Other election workers later looked her up and found she was not eligible to vote due to a conviction, and so her ballot was not counted. Texas prosecutors are now trying to put her in jail. Prosecutors are also pursuing Hervis Rogers, another Black Texan, who is facing up to 20 years in prison for voting while on parole. In addition to the message to Black voters that voting may not be worth the risk, and the use of public prosecutor’s resources, Texas’ system puts strain on elections workers who now need to understand the intricacies of probation rules in order to help would-be voters at the polls. Washington’s current rule, that some formerly convicted community members can vote while others can’t, is similarly confusing to both voters and poll workers. As Mason County Auditor Paddy McGuire explained in testimony (1:15:40): “The current laws on eligibility of former felons to vote are not clear.”

Washington is about to get clear. Thurston County Auditor Mary Hall explained the benefits of HB 1078 for election administrators in testimony (1:10:45) in favor of the bill: “It’s simple, and this is a very clear line—if you’re not currently in prison, you can register to vote and vote. We don’t need any papers, we don’t have to do any research.”

Benefits accrue not just to those who currently are ineligible to vote, but also to those who currently are eligible to vote but might be blocked by the confusing patchwork of rules and election officials’ lack of understanding. When election officials must keep a list of otherwise eligible voters who are ineligible to vote due to a past conviction, sometimes the wrong names end up on the list, and those people are blocked from voting, as happened to dozens of people in Iowa. In Oregon, the rules are clear, and 100 percent of Oregon officials understand them: if an individual has been released from prison, they are eligible to vote. In Washington, the rules aren’t clear, and nearly two-thirds of election officials get them wrong, incorrectly thinking that people with a past felony conviction may need to provide additional documentation when registering to vote. As Sean Morales-Doyle, Deputy Director for Voting Rights and Elections at the Brennan Center for Justice said in testimony (1:22:20): “Elections officials are not criminal experts and shouldn’t be tasked with drawing lines between types of offenses.” Yet, Washington rules have required them to be criminal experts, lest they disenfranchise eligible voters and create the risk of costly litigation against the state.

Whose rights will be restored in Washington?

Compared to the rest of the United States, Washington is already on the less punitive side of felony disenfranchisement. Only 0.87 percent of Washington’s voting-age population, around 45,000 people, are currently disenfranchised due to encounters with the criminal justice system. Nationally, that number is 2.27 percent, representing more than 5 million Americans who have lost their right to vote due to a conviction. These 45,000 Washingtonians, a population almost as large as Olympia, cannot have their voices heard on the everyday issues that affect them: tax policy, school funding, voting accessibility, criminal justice reform, and many others.

And in Washington, as in the rest of the United States, disenfranchisement due to felony conviction disproportionately hurts Black Americans. Black Washingtonians are more than four times more likely to be disenfranchised from encounters with the legal system than the public as a whole. As Sahar Fathi, Policy Director for the Washington State Attorney General’s Office, pointed out in testimony (1:16:55): “Disenfranchising individuals with felony records… has historically served to curb the voice and vote of many from the African-American community.”

In January, around 20,000 Washington citizens currently on probation—close to half of the total number of Washingtonians disenfranchised due to convictions—will have their voting rights automatically restored. That’s a big a population as the city of Ellensburg or Port Angeles. Of those, 17 percent are Black or Native American, populations that comprise just six percent of Washingtonians. Nearly one-quarter of all inmates in Washington are Black or Native American. Not all of them have lost their right to vote. But each year, several thousand people who had lost their right to vote will be released from Washington prisons and will immediately be allowed to vote.

Will they vote?

Formerly incarcerated citizens are less likely to vote than are other Americans. There are many reasons, including:

- Those in prison are more likely to lack a high school diploma, be younger than 35, or have mental or physical disabilities, or have incomes below the poverty line—all factors associated with lower likelihood of voting. The Brennan Center estimates that people being released from prison earn less than half as much annually as their peers with no criminal record.

- Those emerging from prison are 10 times more likely to be homeless than the general public (not to mention those who are housed but move frequently), and election laws make it much harder to register and vote without a stable home address (particularly for mail voting, which Washington has used for all elections since 2011).

- Voting is habit-forming: past turnout is an excellent predictor of current turnout. Those forced to drop the habit of voting while in prison may not re-form the habit once their rights are restored.

- Time in prison is associated with fewer connections to one’s community upon release, and less civic engagement is related to lower voter turnout.

- High rates of incarceration in an area are also associated with decreased turnout in the entire community, not just among those legally disenfranchised (currently or formerly).

- Formerly-incarcerated people may have less trust in government and be inclined to avoid agents of the state (including election officials) due to fears of further criminal punishment.

- Finally, a general environment of disinformation means that many recently-eligible people believe that they are unable to vote, whether by their own misunderstanding or explicit guidance (or the lack thereof) from an election official (“de facto disenfranchisement”).

What’s next?

The Washington Department of Corrections (DOC) is now legally required to inform people exiting prison of voter registration procedures and provide them a paper registration form. The Secretary of State (SOS) is already in contact with the DOC (once a month, with this bill’s passage) to ensure that those currently in prison for a felony conviction are removed from the voter rolls and do not receive a mail ballot at their last address. The DOC and SOS could use this monthly communication to add citizens being released from prison back onto the voter rolls, with the current address they listed upon exit. This would ensure that they would get a ballot in the mail for the next election. The decision to fold any other state agencies into the automatic voter registration system is at the governor’s discretion, in consultation with the Secretary of State and relevant agency heads.

Short of that, the now-eligible voters will get registered by the state’s automatic voter registration system if they interact with the DMV or health insurance exchange.

To help returning citizens re-engage with civic life, non-partisan advocacy organizations should consider hosting voter registration and engagement events in public places in neighborhoods with high rates of incarcerated or recently returned community members. Research shows that such efforts can increase voter turnout in historically disenfranchised communities.

To ensure that these Washingtonians don’t face misinformation when they try to vote, state auditors should consider outreach and education to election officials so they understand that anyone who has returned to the community is now eligible to vote and doesn’t need to show any additional proof.

Clear standards are better for citizens and for election workers

Clear standards are better for citizens and for election workers