It’s charter season! As we speak, Portland’s Charter Commission is examining the city’s governing document for potential improvements and looking for feedback from Portlanders interested in bettering city government. The city charter is the document that outlines city powers and responsibilities like the following: City Council structure and elections, public records and transparency, police oversight, local bonds and taxes, budgeting, transportation and infrastructure, public utilities, economic development, affordable housing, and basically everything else that City Hall is concerned with. While all of these are important topics, the commission has decided to first focus on possible changes to Portland’s commission form of government and at-large method of elections. City Council impacts all of these topics and policies, so making sure that Portland has governing and electoral systems that are effective and responsive is one of the best ways to make sure that solutions are implemented efficiently and equitably. For Portland to be “The City That Works” for everyone, it’s important that the charter-defined structure of government isn’t holding back popular policies and the charter-defined method of elections isn’t preventing a diversity of voices from being heard at City Hall.

Portland’s City Charter is like its constitution

In some US states, state lawmakers write the rules for cities and counties to abide by. But Oregon is a home rule state, meaning that cities and counties have the power to govern themselves through their own charters—kind of like a local constitution—so long as they do not conflict with state or federal law. During the Progressive Era, a time of progressive changes for democracy around 100 years ago, Oregon voters passed a raft of democracy reforms, including a 1906 ballot initiative allowing cities and counties to create and amend their charters without state approval. Oregon is one of the strongest home rule states in the nation: All 241 incorporated cities in Oregon have adopted their own charters, as well as nine of the state’s 36 counties. Another ballot initiative, passed in 1912, gave all Oregon women the right to vote, so Portland women may have had the opportunity to vote on charter reforms in 1913.

The 1913 charter re-write

Once Oregon voters opened the floodgate for voters to be able to change their city’s charter, Portlanders responded by enacting a set of major rewrites to the charter in 1913. Three of those changes drastically overhauled the City Council by enacting the following reforms:

- Reducing it from 15 councilors to just four;

- Changing from a mix of districts and at-large seats to all at-large positions; and

- Changing from a Mayor-Council form to a Commissioner form of government.

This suite of changes squeaked by with a winning margin of just 292 votes (50.4 percent in favor). But the commission form of government has proved hard to shake.

Who could vote in Portland in 1913?

Progressive Era reforms aimed to put more power in the hands of the people, but who exactly was that? The original Oregon state constitution written in 1857, in preparation for statehood granted in 1859, only allowed white men to vote. Article II, Section 6 stated: “No Negro, Chinaman, or Mulatto shall have the right of suffrage.” But in 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment to the American Constitution gave all men, regardless of race, color, or previous servitude the right to vote and the Oregon Supreme Court ruled that this superseded the Oregon Constitution’s ban. Oregon finally repealed this section of the state constitution, officially acknowledging that Oregonians of color have a right to vote, with a ballot initiative in 1927.

American women did not gain the right to vote until 1920, but the western states of Colorado, Idaho, Utah, and Wyoming granted women the right to vote before 1900. Oregon voters made five attempts to follow suit but did not win enough men’s votes at the ballot until the sixth try in 1912, when a Progressive Era ballot initiative gave all Oregon women the right to vote. All Portland citizens, regardless of race, ethnicity, or gender had the legal right to participate in the 1913 vote on major charter amendments. However, of almost 150,000 adult residents at the time (about 900 of whom were Black), only 34,000 cast ballots — less than a quarter of Portlanders at the time. That level of turnout is equivalent to turnout in modern May primaries, but drastically lower than turnout in November general elections.

Only voters have the power to change the city charter

Only a vote of the people can change the charter. A charter amendment can make its way on to the ballot in one of four ways:

- Advocates gather signatures from at least nine percent of the city’s registered voters (right now, that means 41,751 signatures) to put the amendment on the ballot;

- A majority (three out of five) of City Commissioners vote to put the amendment on the ballot;

- A super-majority (15 out of 20) of Charter Commissioners vote to put the amendment on the ballot; or

- A majority (11-14 out of 20) of Charter Commissioners vote to put the amendment on the ballot, then a majority of City Commissioners approve it.

History of Portland Charter Commissions

Portland voters have amended their charter 30 times in the last 80 years, mostly via individual changes proposed by ballot initiative or City Council. These changes have come frequently in the past—in every decade from the 1910s to the 1980s, voters made changes to the charter in at least three separate elections (and sometimes as many as seven). And that’s not even counting the amendments that failed at the ballot! But at the beginning of this century, the City Council thought the charter could benefit from some more systematic updates. The council created a working group to examine the charter as a whole and suggest amendments for the people to vote on.

The first Charter Commission, in 2005, passed three amendments

In 2005, the City Council created a Charter Commission to conduct the first comprehensive review of the charter since 1922. The 2005 commission referred four charter amendments to the voters in May 2007. Three of these passed: one clarifying and standardizing civil service provisions, one requiring a periodic review of the charter through a charter review commission (which received more than 75 percent support), and one increasing city oversight of the Portland Development Commission (now Prosper Portland).

A fourth measure that would have changed the form of government by creating greater separation between executive power (in the mayor and Chief Administrative Officer) and legislative power (in City Council) failed, receiving less than 25 percent of the vote. It was supported by then-mayor Tom Potter and opposed (for a variety of reasons) by the League of Women Voters of Portland; current and former city officials like Bud Clark, Amanda Fritz, Charlie Hales, and Gretchen Kafoury; and several of the Charter Commission members as individuals.

2007 Rule to Create a Charter Commission every decade

Of the several charter commission-proposed amendments that were considered by Portland voters, the most popular by far was the codifying of the Charter Commission itself as a regular process for evaluating the city charter. This amendment created a new section of the charter which explicitly laid out the powers and responsibilities of a regular Charter Commission. City Council would convene such a commission every ten years (starting in 2010), nominating 20 Portlanders that “shall be reflective of the City in terms of its racial and ethnic diversity, age, and geography” for a two-year review process. Council can recommend topics for the Charter Commission to consider, but the commission itself will ultimately determine what it works on. At the end of its deliberation, the commission can refer potential charter amendments to voters, either directly or through City Council’s approval. This amendment was supported by then-mayor Tom Potter, former mayor Vera Katz, and former governor Barbara Roberts.

The second Charter Commission, in 2010, passed nine housekeeping changes

The second charter review started in 2010, as required by a provision in the 2007 amendment establishing the commission. There was an unspoken agreement that because this commission came just five years on the heels of the 2005 commission, it would stick to minor, maintenance-type changes and save the big reforms for the next cycle. The commission referred nine housekeeping amendments to the May 2012 Primary Election ballot. These included removing sections that were unenforceable or outdated, unifying spending requirements across different city funds, and clarifying ambiguous grammar. All nine measures were adopted with more than 75% of voters in favor.

The third Charter Commission is meeting now

City Council assembled a Charter Commission in December 2020, ten years after the last commission. The current charter commission, which will serve for at least two years, is made up of a diverse set of 20 Portlanders, including nonprofit directors, small business owners, union representatives, disability and racial justice advocates, legal experts, and others from across the city who bring their knowledge and experience to the table.

Together, they have identified two major priorities for the first phase of their review—the form of government and elections for City Council. In the second phase of the review, the commission will research topics such as “service alignment and bureau coordination, accountability and transparency, and democracy growth.”

First area of focus: form of government

Portland is the last major US city and the only Oregon city to use the commission form of government (and the only Oregon city with a commission), where commissioners perform both legislative and executive duties by serving as councilmembers and as heads of particular city departments (e.g., Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty oversees the Portland Bureau of Transportation at the time of writing this article). It is also the only Oregon city with a full-time, paid city council—most other cities don’t pay their elected councilmembers at all, and those that do only provide a stipend or a part-time salary.

The commission form started in Galveston, Texas, when a hurricane flattened the area in 1900 – the deadliest natural disaster in American history. A group of wealthy businessmen felt the city could rebuild most quickly and efficiently if there were subject-matter experts in charge of specific city functions. For example, in most commission system cities, candidates would run to head a specific bureau, so someone with a background in policing might run to be the head of the public safety bureau. Progressive Era reformers saw the commissioner form as an opportunity to fight corruption. At the time, politicians would hand out high-level city jobs such as heads of bureaus to their financial backers as a reward for their support. City bureaus weren’t being run by the most competent people, but by wealthy individuals who then used their position to further their own financial interests. The commission form offered the opportunity to make bureau heads accountable to voters in open elections, not to politicians in smoke-filled rooms.

But most cities soon found that any benefits of bureau heads being accountable in elections were dwarfed by the drawbacks of putting lawmakers in charge of agencies. The conflict of interest between their jobs writing laws and passing budgets vs their jobs enforcing laws and spending budgets led to conflicts as commissioners fought for funding for their own bureaus, rather than doing what was best for the city at large. The political conflicts between commissioners turn into coordination problems for the bureaus they head, leading to silos that harm the city because it is unable to take a harmonized approach to complex problems, such as the housing crisis. That’s why almost all cities had moved away from the commission form by the 1960s.

Portland’s commission form doesn’t even offer the accountability that other cities enjoyed. Because candidates don’t run to head a particular bureau, and they might even be re-assigned to different bureaus during their term, voters can’t hold them accountable for how well or poorly the bureaus are run. So Portland’s city government has the disadvantages that turned other cities off, and doesn’t even offer one of the main advantages of the system.

The Portland City Club and League of Women Voters of Portland, two local nonpartisan civic organizations, have authored reports that contain more in-depth discussions of the pros and cons of our commission system.

Past efforts to move away from the commissioner form of government have so far failed

Starting in 1917, almost immediately after the commission form was first adopted, Portlanders have tried eight times to move away from the commissioner form of government, and all eight attempts have failed. The three amendments since 1950 got on the ballot through signature drives (data is unavailable before this), and the most recent, in 2007, was referred to the ballot by Council after the first Charter Commission.

| Year | Changes proposed | Result (percent in favor) |

|---|---|---|

| 1917 | Abolish Commission form | Lost by 17,890 votes (31%) |

| 1917 | Repeal Commission form | Lost by 20,149 votes (28%) |

| 1926 | Simplify Commission form | Lost by 1,699 votes (49%) |

| 1927 | Simplify Commission form | Lost by 30,995 votes (16%) |

| 1958 | Enact Council-Manager form | Lost by 6,538 votes (47%) |

| 1966 | Enact Strong Mayor form | Lost by 26,310 votes (38%) |

| 2002 | Enact Mayor-Council, with seven district reps and two at-large | Lost by 64,449 votes (24%) |

| 2007 | Centralize executive power in Mayor and Chief Administrative Officer | Lost by 41,728 votes (24%) |

Second area of focus: elections

The Charter Commission will also be focusing on topics related to city council elections, including the number of councilors, whether they are elected city-wide or by district (or a hybrid), timing of their elections, and the voting method used to elect them. Portland currently elects six city officials at-large: the mayor (who also serves as a commissioner), four numbered commissioner seats, and the city auditor (a position designed to monitor the efficiency and ethics of city government). Every Portlander can vote on candidates for each position, three seats are elected every even year to create staggered four-year terms, and the candidates do not run under party labels. This system was implemented alongside the commissioner system in 1913, taking over from the previous system where councilors were elected from wards that represented different geographic districts of the city.

The commission form and at-large elections work hand-in-hand, as district-based elections for commissioners would incentivize uneven district-specific approaches to city services. For example, a commissioner elected from a Southwest Portland district who oversees Parks and Recreation might prioritize maintenance and new parks in that part of the city to gain voter support for reelection, while underfunding parks in other districts. Supporters of at-large elections for each council member say that it ensures that councilors are accountable to the entire city instead of just the district or faction that elected them, while detractors contend that it allows a well-organized 51 percent of voters to control every Council seat without representing minority opinions in the legislative arm of government.

Sightline has written two guides to alternative methods for electing legislative bodies (like City Council) and executive officers (like mayor), as well as a 2017 article that discusses some of the issues (and possible solutions) around government and elections that the Charter Commission is considering now.

What happens next?

Charter review is a two-year long process. It got underway this year, and the Charter Commission has gone over the current charter, chosen its areas of focus, established subcommittees, and started holding regular meetings to hear from Portlanders. After learning about residents’ priorities and desires for changes to the charter, the commission will develop proposed amendments that could be sent to the ballot for the city to vote on.

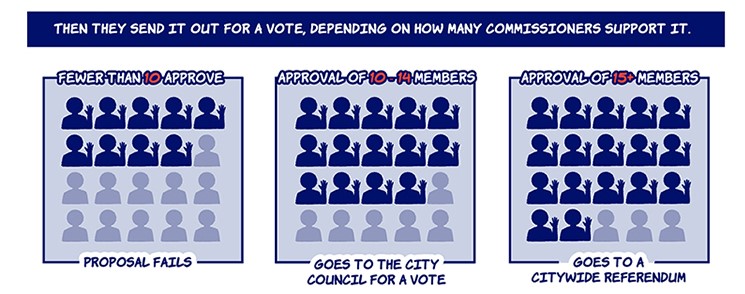

If 15 of the 20 members (75%) support a proposed amendment, it goes directly to voters at an upcoming election. If between 10 and 14 members vote yes, the proposed amendment will go to the City Council, who can edit it and decide whether or not to place it on the ballot. Any proposal that wins fewer than 10 votes on the Charter Commission will fail and not go on.

The Charter Commission hopes to refer their recommendations from phase one (form of government and city council elections) to the voters by June of 2022, which would put it on the ballot in the November 2022 General Election. Recommendations from phase two are planned for December 2022 and would appear on the ballot at a later election. While previous attempts to reform the city’s form of government and elections have failed when presented to voters, public opinion and discussion among civic organizations indicate that now may be the time for change. A 2018 poll found that 70 percent of Portlanders supported electing councilmembers by district rather than at large, up from 54 percent in 2016.

Portland voters will have multiple opportunities to weigh in on the charter review process. The Charter Commission is currently soliciting public comment as they discuss possible charter revisions.

Donna Cohen

Well sourced; I love that!!

Wow, going from 15 to 4 on City Council. Wonder what their thinking was?!

Thanks for the overview!