Takeaways

Seattle has concentrated several decades of population growth within narrow corridors of the city, disproportionately affecting poor and BIPOC communities while failing to ask nearby detached-house areas to evolve and grow as well.

Cities and towns with rising housing costs can address home shortages and inequities by opening up their zoning to new design options, as proposed by a middle housing bill that Washington state leaders are currently considering.

One such design: the Seattle Six, an attractive, economical, adaptable design that enhances neighborhood vibrancy and prioritizes quality of life, environmental responsibility, and anti-displacement. Cities and towns elsewhere can imitate or design their own such solutions.

If you want a healthy garden, you don’t blast just a couple plants with the hose; you water everything slowly so the roots can soak it up. Same with a city or town: sprinkle some housing everywhere, and you’ll get healthier neighborhoods.

Under Seattle’s Urban Village Growth Strategy, the city has funneled 25 years of growth into tightly designated areas without asking adjacent detached-house areas to evolve as well. Along with America’s decades of racist redlining, car-centric design, and the primacy of detached-house building, this kind of strategy has limited what our cities can be. It has sent home prices skyrocketing, deepened racial inequities, and failed to address climate change in how we build our communities. Certain “gentle density” solutions like backyard cottages and townhomes have expanded housing options in tight markets, but for metro areas, the need is greater than these alone can address.

Fortunately, Washington legislators are currently considering a powerful “missing middle” housing bill that would open up a host of modest-sized housing options for people across the state while delivering numerous other benefits for communities. They are reworking zoning rules to empower us to build the future we want. And they are making it possible for architects like me to creatively contribute to the suite of design solutions that can help address the multiple challenges our cities and towns face.

Introducing the “Seattle Six”

As an architect, I see how zoning regulations, good and bad, directly shape the design of buildings. Right now, there is a once in a generation opportunity to conceptualize the next basic building blocks of our towns and cities, starting from a set of key guiding values:

- Healthier neighborhoods focused on quality of life

- Adaptable site design and flexible home configurations

- Deep green construction and inhabitation over a building’s life cycle

- Centering anti-displacement

- New possibilities for ownership, subsidized rentals, and more affordable housing

And while this design was developed specifically for Seattle’s typical lots and market, the values driving it are ones many Washington communities share. This is an invitation—and opportunity—for Washingtonians everywhere to imagine what could be possible in their own neighborhoods.

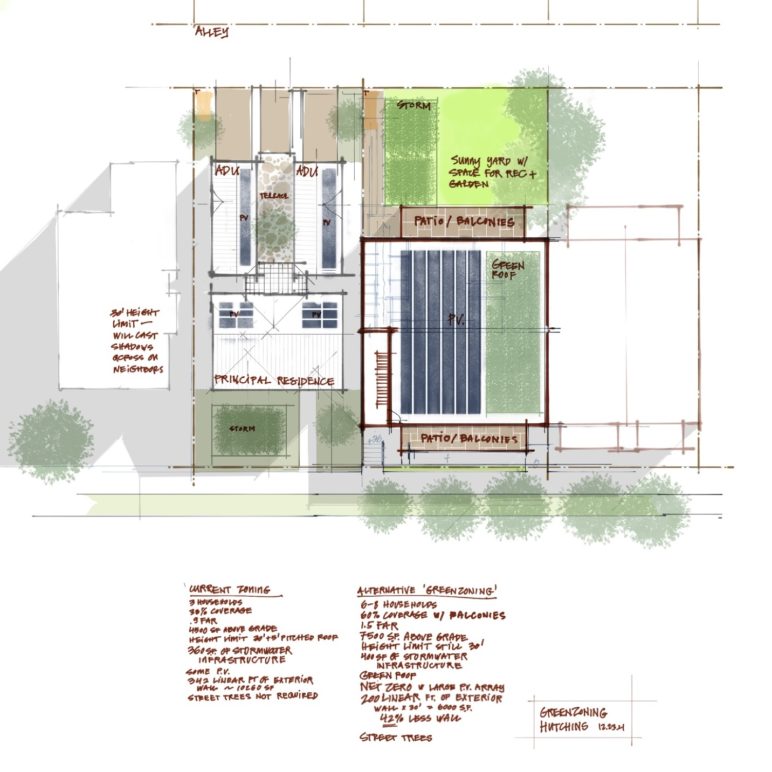

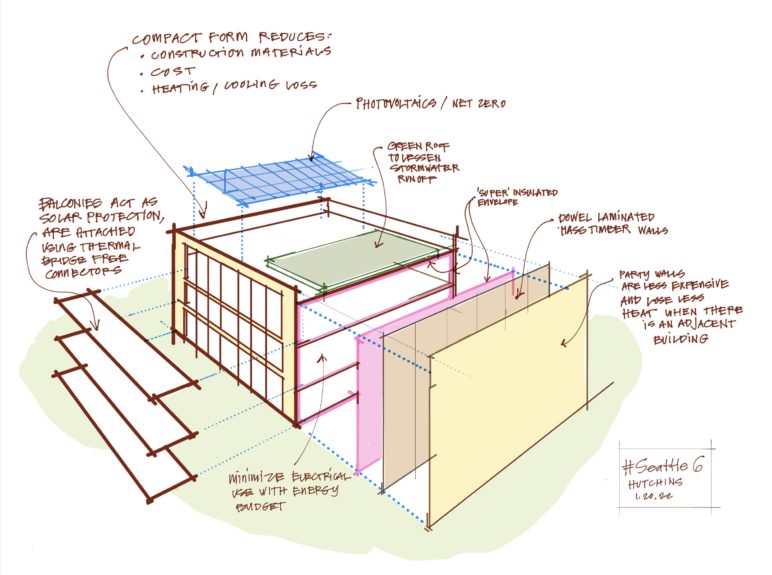

The “Seattle Six” is a three-story apartment building with six to ten households that fits on a range of typical residential lots. It has a compact form that is optimal for deep green building and observes the same height limits as Seattle’s Neighborhood Residential, Residential Small Lot, and Low-Rise 1 zones. In transit-rich areas, it can accommodate additional stories and units. With a floor area ratio (FAR) between 1.5 and 2.0, the Six is still small enough to bypass thresholds that trigger Seattle’s onerous Design Review. And finally, it proposes a clear direction for the urban design of streets and blocks that works in the short, medium, and long terms, aesthetically and economically.

Healthier neighborhoods focused on quality of life

The Seattle Six delivers a range of benefits for neighborhood vibrancy, connection, and attractiveness for residents both in and near Sixes. First, it energizes the sidewalk without overwhelming the street. By reducing the front setback to 12 feet but allowing stoops, covered porches, and balconies in an 8-foot-deep buffer, more residents have access to open space and a connection to life on the street. It replaces the idea of forced façade modulation with the option to embellish and individualize the building, while providing an amenity without complicating the basic structure. Overall, it is similar in height to currently allowed designs and recalls the classic small apartment buildings constructed in the decades before zoning strictures banned them from much of the city.

At the block level, over time, the Six establishes a land use pattern with well-defined urban edges and an interior courtyard in the backyards protected from noise, pollution, and street intrusions. It better preserves existing trees and makes room for new ones, a big advantage over typical oneplexes and townhomes, for instance, which slice up open space into narrow throughways or make backyards the only available land for new housing.

Speaking of backyards, the Six prioritizes access to larger rear yard open space, ample daylight, and options for big terraces for each flat. Units face both the street and the backyard, where kids can play or gardens can flourish, an improvement over another building across a narrow side yard. Residents cycling in will appreciate the design’s easy bike access, accommodating lockable individual bike storage at the ground floor and again in each unit.

What’s more, on an everyday quality-of-life basis for people living in or near a Seattle Six, the benefits multiply. Because denser housing types bring in new families, one block with ten Seattle Sixes would have enough families with kids under five to justify a small daycare. Five more similar blocks would have enough customers for a successful café. Ten more, and you have a walkable/rollable neighborhood with local jobs, rapid transit, retail, services, and restaurants. At corners, the ground floor units could be live/work, corner stores, daycares, or cafes. Because it fits well with detached house neighborhoods, the Seattle Six can locate away from busy arterial streets and near to places like parks, schools, and libraries, bringing more vitality to every block.

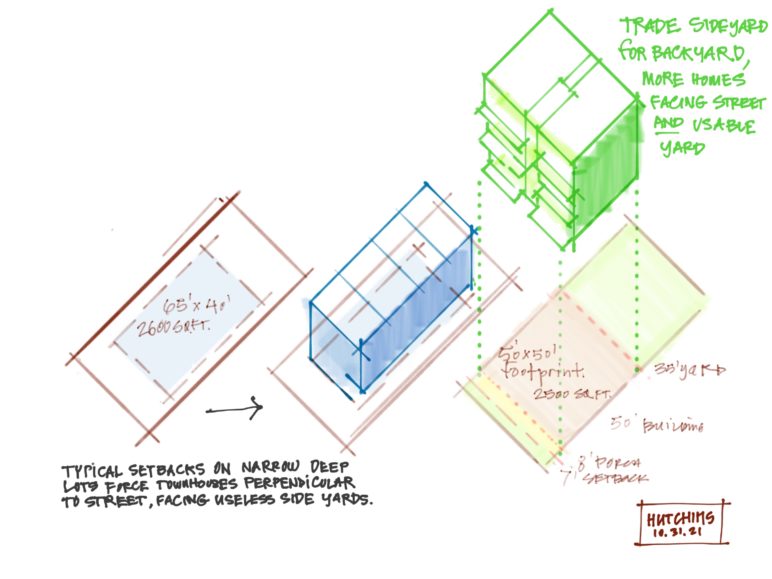

How a block can grow (click on images to enlarge): Top left: typical block of detached houses. Top right: typical townhouse development that would result in tree loss and inefficient use of open space. Bottom left: Ten Seattle Sixes sprinkled through the block. Bottom right: a full block of Seattle Sixes, showing how exchanging narrow side setbacks for larger back yards creates far more useable open space and more room for big trees. Illustrations by Matt Hutchins, used with permission.

In most cases, building a Seattle Six would require demolition of an older structure, just as a big new oneplex does today. This is exactly why Seattle should also allow alternative infill options like backyard ADUs and small-plexes that can coexist with older structures that remain in fine shape.

Adaptable site design and home configurations

The Seattle Six supports a range of household sizes, multi-generational living, and moving within the building as life situations change. One can downsize and “age in place” or upsize as their family grows without having to give up the community of neighbors they’ve gotten to know.

Ground floor and typical upper floor plan showing flexible range of unit types (click on images to enlarge). Illustrations by Matt Hutchins, used with permission.

Even on lots smaller than the 50’x100’ Seattle standard, the design is flexible enough to offer a variety of unit sizes. Floors can be a mix of family-sized one- and two-bedrooms; they can combine into one large multigenerational floor and later split into a principal flat and mother-in-law; or they can comprise a sprinkling of studios. A single central stair optimizes each floor for living space rather than the dark double-loaded corridors typical of larger apartment buildings. The version shown below is built on a concrete slab at grade level, but a partly below-grade floor of garden units would be practical depending on the topography.

The ground floor features accessible units via ramp, as well as a flexible studio. Residents can use it for a variety of purposes: for residents with temporary disabilities, housing a caretaker, or a short-term guest suite. Alternatively, it could be a common room, hosting things like teen game nights or get-togethers in a co-housing community.

Deep green construction and inhabitation over a building’s life cycle

Buildings are a major source of climate emissions, but they don’t have to be. They can incorporate deep green construction that reduces a building’s embodied and operational carbon.

To this end, the Seattle Six is conceived using Passive House principles in its design. The Six’s simple, compact form, continuous insulation to keep interiors comfortable at a consistent temperature, and shared party walls reduce energy loss, paying back residents with a lifetime of low heating and cooling demand. Paired with rooftop photovoltaic panels, the Seattle Six can be net zero energy.

As for materials, the Six’s structure is designed with a dowel-laminated timber structure, which sequesters carbon and minimizes the need for concrete or steel, resulting in a low embodied carbon construction. The mass timber party walls and stair core satisfy the fire resistance rating. And bonus: it can be remanufactured for use in a future project as part of a more circular economy.

The Six also accounts for its region’s natural environment. Its green roof and on-site storm water management limits runoff from the site. And as wildfire smoke becomes more commonplace, the Six’s heating recovery ventilation system not only saves energy but filters pollutants to supply fresh air throughout the building.

Countering displacement

The goal of Seattle’s Urban Village growth strategy was to concentrate new housing around commercial centers and serve them with an expanded transit network. But the strategy’s zoning changes disproportionately landed on poor or BIPOC neighborhoods, such as the Rainier Valley. The consequence has often been a cycle of speculation, displacement, and gentrification at the expense of people who’ve built their lives there.

Having a small apartment building that can plug in anywhere, starting in areas the city characterizes as having “low displacement risk” (i.e., most residents have the means to stay in their homes or find other housing nearby), would reduce the pressure on housing in other, less expensive areas. In a city like Seattle that’s adding lots of jobs, building lots of homes is essential—and the Six is a template for every neighborhood to do its part.

Allowing six or more households to divvy up the cost of Seattle’s pricey land lowers housing costs, too. Efficient, modern buildings like the Six would offer a mid-sized and mid-priced option between detached houses or townhouses on the one hand and large apartment buildings on the other. Indeed, Sightline recently analyzed possible development scenarios under Portland’s new zoning code. It found that new triplexes and fourplexes weren’t quite financially viable there in most cases, but that sixplexes in Seattle’s more expensive market might be.

In other words, the Seattle Six fights displacement in exactly the same way it fights segregation: it creates a new, cheaper way for people to live near jobs, parks, schools, and good public transit while reducing development pressure on other vulnerable neighborhoods.

New possibilities for ownership, subsidized rentals, and more affordable housing

We’ve underproduced housing for nearly a generation, putting even the most modest starter home beyond the reach of most Washingtonians. In just a decade, the state’s median home price has increased by 237%. Rents are on a similar trajectory, rising 183% for a two-bedroom apartment over the same period.

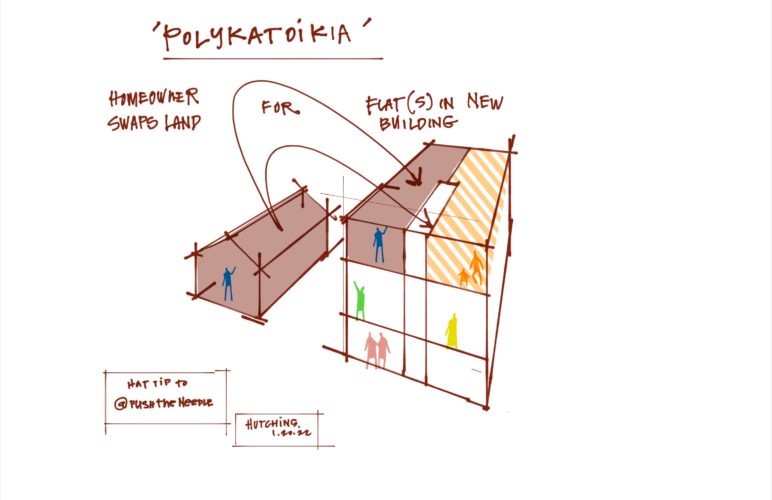

Whatever form new development takes, we’ll also need creative forms of ownership: co-ops, urban co-housing, and condos, for example. One interesting idea well suited for Seattle is the Polykatoikia, where landowners who are cash-poor but land-rich negotiate with a developer to swap a new apartment building on their land in exchange for a flat or flats in that new building. It is an excellent way for local landowners to maintain and grow generational wealth, stay in their neighborhoods, and create new homes in the process.

To the south, Portland’s Residential Infill Project allows developers to build extra units in exchange for affordable housing. The Seattle Six framework could easily support more households, too: either with an extra floor or a smaller height limit bonus to add a level of garden suites. Seattle’s Mandatory Housing Affordability performance option won’t help private developers create on-site affordable units given the small scale, but perhaps some of the MHA payments taken in by the Office of Housing could be deployed to finance small apartments, similar to how the Equitable Development Initiative has been supporting anti-displacement efforts.

Building the tomorrow we want, today

It is a watershed moment for Washington: an opportunity in our housing policy to address climate change and racial inequities while building the homes we need and communities we want. The Seattle Six is just one model of how that might look. It’s also an invitation, as state leaders consider critical middle housing legislation, for communities across the state to boldly envision the future they want and build it into reality.

Comments are closed.