British Columbia is a far wealthier place than it was a decade ago. It has also become a prohibitively expensive place to live for more and more working families, young people, and renters of all ages, thanks to ballooning housing prices. And those high prices are inflated by a tax system that encourages speculative investment in residential property with three key policies: low property taxes, the principal residence capital gains tax exemption, and the provincial homeowner grant.

Who has profited from these speculation-friendly tax policies? The people who own most of the land in Vancouver: our neighbors and friends. It may also be significant that most of our elected leaders own property: 93 percent of the members of British Columbia’s legislative assembly are homeowners, with half of those owning more than one property. In the rush to tax the bogeymen of foreigners and owners of vacant condos, a basic fact has been largely overlooked: the speculation is coming from inside the house, as homeowners who were fortunate enough to buy at the right time have quietly benefited handsomely from an unjust tax system.

These three policies enrich homeowners while driving up housing costs for everyone else. They allow private landowners to capture increased property value created by the community as a whole through its labor, public services, and contributions to the city. And while these policies have not received nearly as much media or government attention as taxes on vacant homes or foreign buyers, they are a greater contributor to Vancouver’s spiraling housing costs.

“…there’s no wiggling out of the reality that housing cannot be both affordable and a lucrative investment; prices cannot go up and down at the same time.”

Threatening the value of what is most residents’ biggest personal investment is a political challenge, to say the least. As British Columbia Premier John Horgan acknowledged, “people have equity in their homes, we need to be mindful of that.” At the same time, elected leaders in charge during a drastic loss of affordability will face political challenges from those left behind. But there’s no wiggling out of the reality that housing cannot be both affordable and a lucrative investment; prices cannot go up and down at the same time.

Policymakers hoping to fix British Columbia’s affordability crisis can no longer ignore the need to raise property taxes, limit the capital gains tax exemption, and end the homeowner grant.

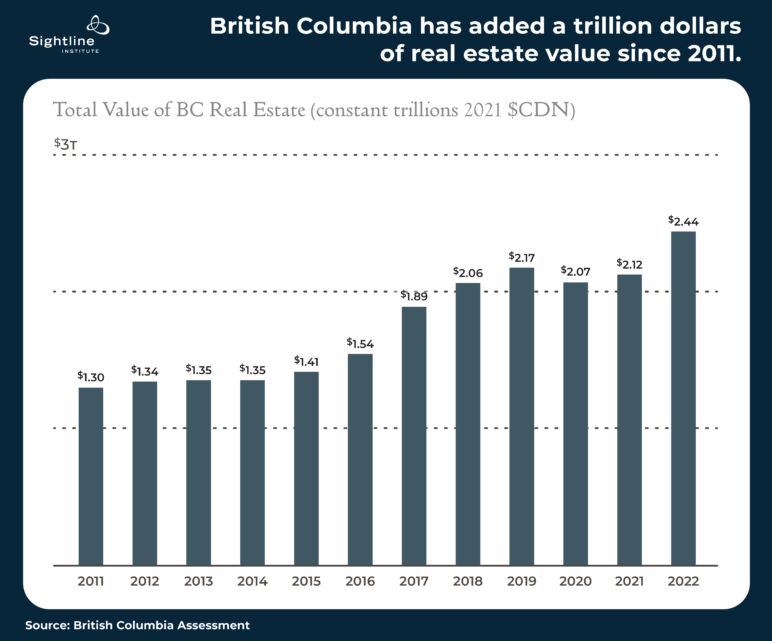

A Trillion Dollars in New Property Wealth

The paradox of Vancouver’s housing crisis is immense gains in land wealth accompanied by poverty and desperation caused by rents and home prices surging out of control. Property values in British Columbia have almost doubled in the past decade (even when adjusted for inflation), increasing from $1.3 trillion to $2.4 trillion. Some of this increase is from new construction, but about two-thirds of it is property owners getting richer in their sleep.

The new wealth works out to $220,000 for each of BC’s 5 million residents, or $22,000 per person per year. But not every British Columbian got $220,000 richer. Many owners of detached homes in Vancouver’s central neighborhoods made millions while most renters got nothing besides steep rent increases.

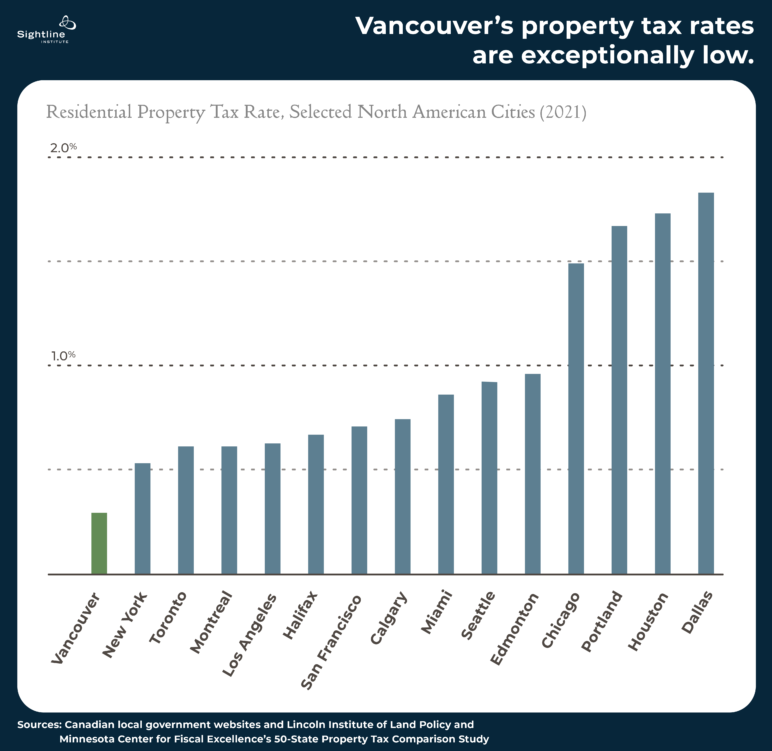

Vancouver’s Exceptionally Low Property Tax Rate

The property tax rate in British Columbia’s largest city, Vancouver, has declined by more than 50 percent since 2000 and is now among the lowest in North America (see chart below). It’s only because property values have risen so much over the past two decades that the city has been able to maintain sufficient property tax revenue at ever lower tax rates.

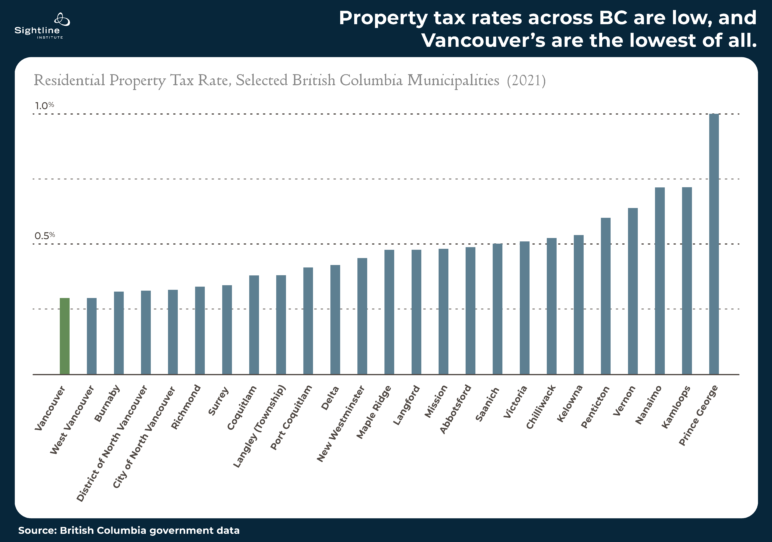

Property taxes in other BC cities are also low (see chart below). For example, although British Columbia’s capital, Victoria, has property taxes that rank relatively high among BC municipalities, it still has the second lowest rates on the chart above, which includes cities across North America.

Low Property Taxes Boost Prices and Speculation

All else equal, when property taxes go down, home prices go up. In Portland, Oregon, for example, the owner of a typical million-dollar home would pay $16,000 a year in taxes, compared with just $2,900 for a home of the same value in Vancouver. That’s a difference of more than $14,000 per year, or $1,000 a month. Another way of looking at this is that, depending on the interest rate, that’s about the same as the difference in mortgage cost between a $1,000,000 home and an $800,000 home.

Smaller property tax bills mean that buyers can afford higher purchase prices, driving up home values. New home buyers pay the same amount either way, but an important difference is that with higher property taxes, more of the payment goes back to the public through taxes, rather than to banks through mortgage payments.

Low property taxes also boost prices by encouraging speculation, because a lower tax burden reduces the cost of holding a property while owners wait for its value to rise (known as land banking). As Vancouver City Councilor Christine Boyle explained, Vancouver is “an appealing place for people looking to invest in housing, because the carrying cost of that investment is low, and the increases in value are high.”

Like most property taxes, Vancouver’s taxes apply to the property’s land value and to the value of the buildings or other “improvements” on that land. The land tax portion is beneficial (tax skeptic Milton Friedman called it the “least bad tax”) because it encourages maximum economic use of land. Or as Jerusalem Demsas wrote for Vox, “taxing land reduces the profit that comes from just owning a piece of property. Instead, you are incentivized to put that land to work.”

In valuable urban locations, putting the land to work means less land banking and more homes, shops, services, and jobs. In contrast, the portion of the property tax on buildings discourages their construction. The relative size of the two property tax components determines whether the net effect is good or bad.

Raising the rate of just the land portion of the property tax would deliver greater affordability benefits than would raising the rate for land and improvements equally. In fact, Vancouver imposed higher rates on land than on buildings until the 1970s, when the provincial government rescinded that taxing authority. BC Assessment still records separate assessments for land and buildings, so that transitioning back toward a land value tax would be administratively simple, if not politically so.

Fortunately, even if provincial law continues to bar taxing land and buildings at different rates, in Vancouver, raising the entire property tax would still be a disincentive to speculation and land hoarding and a net positive for affordability. That’s because low-density detached houses and duplexes are built on about 80 percent of Vancouver’s residential land. These structures are usually worth a fraction of the lots they occupy (a ratio of one to fifteen is typical).

Ideally, an increase in property tax would be coupled with legalization of more homes per lot in the city’s detached house zones. That would not only offset any deterrent to building new housing caused by higher taxes but also channel the land tax incentive into the construction of modest multi-dwelling homes instead of big and pricey houses for just one family.

The Capital Gains Tax Exemption on Homes Is a Giveaway to the Rich

Low property taxes aren’t the only problem. Canada’s federal government also exempts capital gains on principal residences from taxation, giving preferential tax treatment to those who use their home as an investment vehicle. A renter who invests in the stock market will pay capital gains taxes on those earnings, but their neighbor who put their savings into purchasing a home will pay no capital gains tax on increases in that home’s value. There is no limit to the exemption, so the owner of a detached home in Vancouver that has appreciated by $3 million (or even $30 million) will still pay $0 in capital gains taxes.

For Canada, in 2021 the estimated cost of this exemption, in terms of forgone tax revenue, is $7.1 billion. It’s an annual subsidy to homeowners equivalent to the entire annual cost of Canada’s National Housing Strategy. And, as noted in a recent editorial in the Globe and Mail, this “housing tax break is one whose biggest benefits flow to those with the deepest pockets.”

The United States federal government doles out similar market-inflating incentives, including a capital gains tax exemption, but it only exempts up to $250,000 per person (or $500,000 per couple). And like Canada, the United States does not tax imputed rent. As Sightline’s Alan Durning wrote,

Tax breaks and hidden loan subsidies encourage speculation in home values. They cause buyers to put more money into their homes and less into other, productivity-enhancing investments. They bid up home prices in zoning-constrained high-price markets and escalate house and lot sizes at the top end of the market in more sprawling, less-expensive markets. …It also exacerbates inequality. Because the tax breaks are much more valuable to households in high tax brackets, they skew the housing market away from first-time and entry-level buyers, who are mostly in lower tax brackets.

Canada’s capital gains tax exemption on homes has funneled billions of dollars into real estate, inflating prices at the expense of affordability for anyone not fortunate enough to own their home. Both owners and renters pay income tax to fund public services. Business investors pay taxes on their profits or gains in the market. But homeowners can make hundreds of thousands (even millions) of dollars tax-free, without any corresponding contribution. This is a tax advantage that makes investing in one’s home extra attractive relative to other options.

BC Residents Get a Check from the Government Just for Owning a Home

If you live in BC and own a home, the provincial government will send you a check for at least $570 every year. For seniors residing outside major metropolitan areas, the grant can increase up to $1,045.

The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives estimates that this payment to homeowners costs the BC government $840 million every year. Owners of homes worth more than $1,975,000 are not eligible, but that’s only 8 percent of BC properties. Because the homeowner grant so blatantly benefits owners but not renters, the BC Expert Panel on the Future of Housing Supply and Affordability has called for phasing it out, asking officials to “consider the unintended consequences of policies that concentrate benefits on one group at the expense of the remainder of the population.”

In both their 2017 and 2020 election campaigns, the New Democratic Party responded to this inequity by promising a renter’s rebate of $400. But the New Democrats have now been in power for more than four years and the renter’s rebate has not yet materialized.

Five New Taxes and Record Home Prices

In response to rapidly increasing home prices over the last decade, the city and province enacted five new taxes with the ostensible goal of improving affordability:

- a foreign buyer’s tax of 15 percent on the purchase price (introduced by the Province of BC in 2016);

- a 5 percent land transfer tax on the value of transferred properties exceeding $3 million (Province of BC, 2018);

- an annual vacancy tax of up to 1.5 percent (Province of BC, 2018);

- an empty homes tax of 3 percent (City of Vancouver, 2017); and

- a luxury homes surtax of 0.2–0.4 percent per year (Province of BC, 2018).

The vast majority of BC homeowners are exempt from these taxes. (The vacancy tax, for example, hits just 1 percent of British Columbians.) The new taxes are so limited in reach that it was always hard to believe that they would significantly reduce prices. In contrast, low property taxes and the capital gains exemption apply to almost every home, and push prices higher.

The five new taxes have, at best, nibbled away at the margins. At worst, they have scapegoated people of Chinese descent while shifting attention away from tax policies that really do drive speculative price inflation. In 2017 Sightline wrote that the foreign buyer’s tax would only “help some in the short term at best,” and recommended that “the best solution for ending speculation is to build enough new homes.” Seeming to confirm that prediction, Vancouver’s home prices reached new peaks in 2021 and 2022, despite these five new measures.

To Cool Speculation, Tax Land

Adding more than $1 trillion to the collective wealth of British Columbians over a decade presents a historic opportunity. British Columbia’s rising wealth offers the promise of lifting everyone up and spawning a new era of shared progress. But low property taxes, the capital gains exemption, and the homeowner grant have helped channel too much of those wealth gains into the pockets of homeowners and widened the divide between rich and poor.

“…when a new transit line opens, a nice new restaurant enters the scene, or a large business that offers high salaries comes to town, the value of all the nearby property increases without the owners lifting a finger.”

As Vancouver’s record-high home prices attest, the five new targeted taxes aimed at cooling speculation implemented since 2016 have been no match for the much more powerful speculation-boosting tax policies. Policymakers’ narrow focus on bad actors and outsiders was based on a faulty assumption that the existing tax structure was fair and efficient.

Low property taxes and home capital gains tax exemptions not only line the pockets of homeowners while squeezing renters; they also allow private owners to unfairly capture value created by community members’ public and private investments. After all, when a new transit line opens, a nice new restaurant enters the scene, or a large business that offers high salaries comes to town, the value of all the nearby property increases without the owners lifting a finger.

The political obstacle is obvious: most homeowners have made out exceedingly well under the existing system, and they have a vested interest in keeping things the way that they are. But the political imperative for reform is just as obvious: as more and more people are priced out, the constituency demanding more equal access to the land and its profits will only grow louder.

For leaders looking to lower housing prices, the remedy is clear: tax capital gains on homes and raise property taxes—and, ideally, raise the tax rate on land, not buildings. These actions would cool speculation and reduce pressure on prices. And more of the unearned property value gains the community as a whole creates would be returned to the public as tax revenue—revenue that cities could use for affordable housing, transit, and improving the lives of all residents.

Morgan

Hooray for Henry George! Taxes on homes, however, are highly regressive and is anti-aging in place.

Here in Washington, I’d like us to continue working toward a state income tax, since radical income inequality is, as best I can tell, our primary and dominant cause of housing inequality.

Tim DuBois

The argument is a tax on land not the homes. Please explain why that is regressive? And we should in no way think the idea of aging in place is good. Why would we want empty nesters to capture the limited affordable family size homes in perpetuity when their housing needs have dramatically changed? It makes no sense. I don’t encourage pushing elderly into group homes, I think that is borderline a moral sin, instead aging elderly should move in with their adult children, like most of the world does. And if you have no adult kids then a group home is then fine because that is a decision one made early in life that had many positive benefits early on.

Daniel Oleksiuk

The problem of wealth inequality must also be dealt with, and in Vancouver wealth inequality is most evident in land wealth. One benefit of land taxes is that only land owners with significant increases in land equity will see increases in taxes, so that the increased equity will more than offset the taxes. No one should have to move, since only richer people will have increased taxes. Some may choose to move, but no one would have to.

Aging in place, with a surprising windfall of land equity, is the default state of most of Vancouver’s older homeowners. A higher land tax would merely share some of that windfall.

British Columbia also has generous property tax deferrals for people 55 and older, so that the taxes don’t need to be paid until sale.

Taxpayer

How about increasing supply to meet demand?

More tax won’t solve bidding wars to rent basement suites.

Tim DuBois

Did you read the article? The main underlying point is that the current tax and subsidy regime creates a disincentive to add supply. Furthermore by changing the structure government would not in fact be increasing the cost burden of new homeowners but rather shift it away from banks and real estate agents (my addition to the argument) and towards the public good. So for those who currently own a home if these changes were to occur they might complain about higher taxes. But they would have a simple solution to reducing it. Build more homes on your property. It could potentially even reduce your tax burden. And to repeat if you are new to buying a home you can still only afford so much new home and that amount would shift away from the bank and move towards your community. It really is win-win unless you are someone who cares less about solving our housing epidemic and instead really just hate density. Which then why live in a city?

R H

So …..tax people out of their homes to provide more housing? Homeowners have not caused the cost increase, demand has increased the cost. Increase housing to control housing cost.

Santos

Try looking at American taxes for home\land value……way higher…but they can write of interest of mortgages….so they can save that

David

Correct. And one of the spouses can write off the cost of a boat considered a second home.

Ken March

Wow your assessment of taxes in Vancouver vs Portland is totally wrong. I just googled property tax in Portland Oregon and found the rate to be 0.09% and the tax to be approximately $2600. With Vancouver’s rate of 0.3% the average tax is double or over $5000.

It is easy to manipulate the numbers when you only tell half the truth.

Daniel for an educated person you are lying to the people. Or should I say you are manipulating the numbers to suit your truth.

Do I agree house prices in BC are High no I don’t but there is no better place to live and that is why our prices are going up. As I spoke to a recent new Canadian who is trying to buy a house here he stated ” we moved to Vancouver from Halifax because it is a better place to live.” And lets face it Vancouver is constantly rated as one of the best places to live in the World.

As a senior in Vancouver with a small fixed pension taxes are very high on top of my mortgage. I too spend more than 40% of my income on only mortgage and property tax. When I purchased more than 10 years ago this property was over $1.2 million and now is just $2 million. Not a very good return for the investment. If I put that money in my investment account it would be close to $5 million now. (in 2011 when I bought my investment account was just over $200,000 now it is almost a million) Yes it is hard to own a place and as a young buyer I thought I would never own a house but I worked at it and after purchasing I had to beg and borrow cash to put gas in my car to go to work. For 5 years I had to scrape by just to make payments on my 18% mortgage. My mortgage payments in 1981 would fund a $650,000 mortgage today.

So if I made a little money on my home I paid dearly for it in stress and compromise in lifestyle. No holidays and pay out of my vacation time to just make my payments.

Put the property tax into perspective I pay over $7000 per year in property tax that the same house in Portland would pay far less property tax probably less than $3000.

Daniel Oleksiuk

We readers can’t know what you googled, but your numbers for Portland property taxes are way off.

You can look up the tax paid for any address in Portland on the Multnomah County website here: https://taxgraph.multco.us/

The rates do vary and it is a bit confusing, but no rates are 0.09% as you claim. I found them to be in line with the figures from the Lincoln Institute report that I rely on in the article.

R H

So …..tax people out of their homes to provide more housing? Homeowners have not caused the cost increase, demand has increased the cost. Increase housing to control housing cost.

Tom

I 80% agree with this. The 20% that’s missing is that we need to cut out property speculation until we get this supply crisis under control. Just like when we overfish the Fraser, we need to hit pause for a few years and let the stocks recover. Building more housing while speculators remain on a feeding frenzy just leads to fatter speculators, who then just speculate more. Stocks will not (and can not) recover until this happens.

Marina Verenitch

I live in Los Angeles which is much more expensive than Portland. We do not pay that taxes for the house and no one around me paying that much , unless you look on 15 million property . It’s not true.

Wei

The principal residence capital gains tax exemption does encourage speculation and home owners to trade more often. It is the reward for homeowners who take the risk of losing money (trust me, housing market does not have only one direction).

However, termination of this tax exempt will not improve affordability simply because less frequent changing-hand doesn’t mean lower price. The high desirability of Vancouver alway attracts newcomers and new home owners. On the other hand, the loss in land transfer tax is a big hit for NDP budget.

You misunderstand the causative relationship between the housing price and urban development.

Please note that the property tax is a critical source for the urban development in Vancouver.

An increased property tax will definitely discourage home ownership and cause price drop. Unfortunately, it will not increase housing affordability because the increased tax simply eliminate benefit of the price drop.

Affordability comes from the balance of supply and demand by the market force. Tax is a government tool to interfere with the market. It may lead to unexpected consequences.

Daniel Oleksiuk

The great thing about a land tax is that people don’t stop producing land when you increase it. They don’t shut down their land factories. There are no land factories- the land already exists, and a tax does not change the supply of land.

All that happens is that people who were profiting off of land that they did not make, can no longer profit while sleeping, and the social value of land goes back to the public.

Tom

I feel you’re on the right track, but you seem uninterested in the impact on typical homeowners. Yep, my neighbour bought her house 60 years ago for $40,000. I don’t hold her new wealth against her. Increasing her taxes would be changing the game unfairly, which is exactly what us Millennials are so mad about. The game changed. The gameplay we were told would work doesn’t work any more. We’re suddenly playing a game of Monopoly where the properties on the board quadrupled in price (along with rents), but we still collect just $200 when we pass “Go”.

Typical homeowners aren’t the issue. The problem is the speculators. People who own multiple homes, and rent them out at sky-high rents. That’s who taxes should be aimed at.

A better solution would be to jack up property taxes by something like 1000%, but also INCREASE the homeowner grant to cover 90% of that increase, so the typical homeowner who owns their homes taxes might jump from $4000 to $40000, but the grant brings it back down to the original $4000 they’ve always paid. People who own a second home – a vacation home or something like that – also get a rebate, but it only covers 70%. Third homes get 50% back. Fourth homes or more pay the full tax.

Under this system, much of what you’ve written about still works, but Granny doesn’t get dinged with an outrageous, punitive tax bill just because she got lucky. People who behave in typical ways shouldn’t be treated unfairly. But it does plug some of the holes in our system that allow for runaway speculation.

PeterL

Property taxes in Vancouver are low, as a percentage, because they’re calculated by dividing the city budget by the total property values. So, when house prices go up, property tax percentages go down. That doesn’t mean the taxes go down — they typically go up each year by the amount of the city’s increased spending.

If you look at the density of Vancouver and the density of San Francisco, you’ll see that the tax per square foot is roughly the same in both cities, but Vancouver is 2x denser than San Francisco. City services such as roads and sewers are roughly proportionate to the area that’s being serviced, so a given amount of taxes serves twice as many people in Vancouver compared to San Francisco. Vancouver also seems to be better managed — the streets are in better state of repair than San Francisco, and the quality of other services (education, parks, health) is also better (this is my subjective feeling after visiting both cities).

As for the principal residence capital gains tax exemption — mortgages aren’t tax deductible in Canada. That’s not a great reason; but in the US, the first $500K of capital gains isn’t taxable (in effect giving no capital gains for most housing away from the two coasts) and the mortgage is tax deductible.