The latest North American city rethinking its low-density zoning for better affordability and sustainability is one of the epicenters of modern zoning reform: Vancouver BC. Can their six-homes-per-lot plan work for affordability?

For decades, Vancouver has led the continent in re-legalizing small accessory homes: basement units known locally as “secondary suites” and alley-facing backyard homes, called “laneway houses.” Now, as those ideas have radiated out to Washington, Oregon, Idaho, California, Alberta, Alaska and elsewhere, Vancouver is brainstorming new ways to legalize housing.

On Monday, Mayor Kennedy Stewart laid what looks like some of the groundwork for a 2022 re-election campaign by endorsing what could be Vancouver’s next step: up to six homes on any owner-occupied lot if at least two are made permanently affordable to middle-income households.

Stewart’s office calls it a “four plus two” plan. As another option, the proposal would legalize four full-size homes if one is made permanently affordable to middle-income households.

“Imagine a Vancouver with homes the middle class can afford,” declares the splashy website unveiled Monday by the coalition supporting Stewart’s proposal. It’s branded “Making HOME.”

Stewart was elected in 2018 on a pro-housing platform. It’s a perennial issue in this deeply housing-scarce city at the heart of a region that almost completely banned suburban sprawl in 1974. Since then, the region has tried various ways to instead build upward and inward, from condo towers near suburban rail stations to basement cottages citywide.

Vancouver’s unique lack of sprawl has created a city and region with impeccably green lifestyles—the lowest carbon emissions per person in North America—but crushing home prices. In a city where the median household earns $80,000, or about $62,000 in US dollars, the median home sells for $1.1 million. It’s one of the worst income-price ratios in the world.

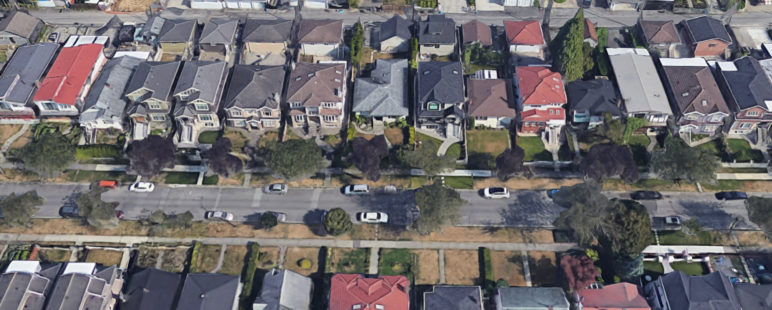

Stewart’s proposal looks for a solution to Vancouver’s land shortage in the 57 percent of the city that zoning laws currently set aside for low-density, high-income housing.

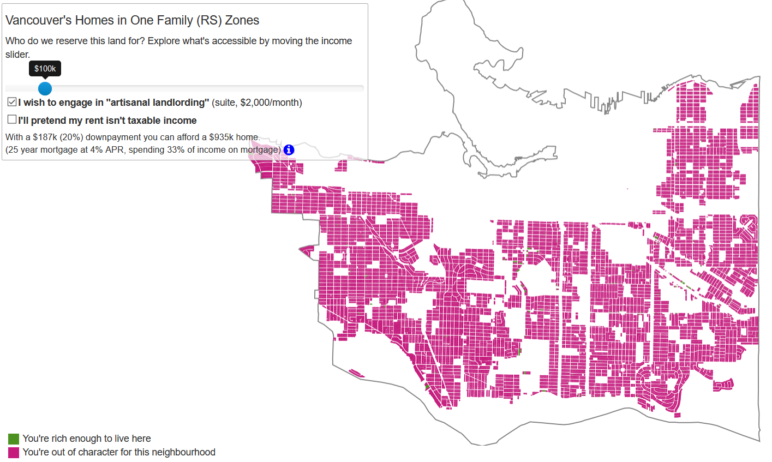

As Vancouver data analyst Jens von Bergmann pointed out in 2017, almost no one with an income below $100,000 can afford to buy a home almost anywhere in the so-called “RS” detached house zone, even with help from housemates in the basement.

Image from interactive map by Jens von Bergmann.

“Honestly, I don’t know who we zone RS land for.” Von Bergmann wrote then. “The 23,310 households with income over $200,000?”

Stewart’s “Making HOME” proposal is to fix this, allowing six homes per lot and thereby creating new homes in the RS zones that households earning $80,000 could afford to buy.

Slide from media briefing by the office of Vancouver Mayor Kennedy Stewart, for his Making HOME campaign.

Middle-class affordability in one of the world’s least affordable cities? With no public subsidy? It sounds almost too good to be true.

Is it?

I decided to try to find out.

In most cities, this proposal would not work

The idea of legalizing infill housing if and only if some of it is cheap isn’t new. Many cities, including Vancouver, do this for new apartment buildings.

In many cases, proposals like this are basically hoaxes. Letting someone build fourplexes, but only if they’re cheap, can be like telling someone they can sell as many ice cream cones as they want, as long as the price is 15 cents. It can be a way to look good while ensuring that nobody actually gets cheap ice cream.

At first, this looked like one of those cases. After all, Stewart’s pitch doesn’t seem to include any public subsidy.

But I also noticed Stewart’s proposal is vague on other crucial details: building size, height, and how many parking spaces the city would require.

Stewart’s goal is to let city staff hammer out those details based on data. But to get an advance look at what those data might show, I called up two Vancouver experts: Bryn Davidson, a small-scale developer, and Darrell Mussatto, a former suburban mayor turned zoning-reform advocate.

Here’s what they told me.

In Vancouver, this could work. But buildings would have to get bigger

In Vancouver, both the six-homes-per-lot concept and a smaller-scale fourplex option (with a single below-market home) could work financially. The reason for this is buried inside the reason new market-rate homes in Vancouver are mind-bogglingly expensive at about $1,000 per square foot. (That’s $1 million for a modest 1,000 square foot two-bedroom.)

Unlike in San Francisco, for example, Vancouver’s astronomical home prices aren’t significantly driven by construction costs. Vancouver’s labor and material costs are very similar to those in similar metro areas. (In Vancouver, Davidson told me the construction process costs something in the range of $350 per square foot, which is around $270 in US dollars.)

Instead, Vancouver’s housing price crisis is driven by its crazybananas land costs, which are in turn driven by Vancouver’s decades of housing scarcity. (Vancouver’s housing scarcity is itself due in part to people investing in Vancouver without building more of it. But external investors are not the bulk of Vancouver’s problem … and anyway, empty homes in Vancouver would stop being a good speculative investment if the region were building enough homes.)

This land-value math is different in cities like Portland or Seattle, where land prices are less extreme and newly built market-rate homes generally sell for $500 or less per square foot. This means that most of the cost of a new home comes from the actual cost of building it. Portland’s new mixed-income sixplex option, for example, isn’t expected to be widely used except by nonprofits that can bring in additional subsidies. (Writing in The Tyee, Vancouver architecture professor Patrick Condon doesn’t seem to be aware of this crucial fact about the Portland plan.)

But in Vancouver, Stewart’s proposal could work. Because when the fundamental problem is land costs, there’s a simple path to lower costs: allow the land value to be divvied up among more households.

As Condon notes in a second Tyee article, this share-the-land effect isn’t enough to make newly built market-rate homes cheap, because in a scarce market, land prices depend to some extent on the number of homes you can build there. What Condon’s analysis ignores is that putting tighter price requirements on hypothetical smallplexes ignores the real enemy of affordability: stasis. Unless Vancouver starts to price-regulate oneplexes as well as smallplexes, Vancouver wouldn’t see much change under Condon’s proposal—just a bunch of older oneplexes remaining right where they are, their market-rate prices rising like the temperature of water that slowly boils a frog.

So, to recap: The Making HOME proposal wouldn’t be enough to make market-rate homes cheap. But it could create some below-market homes without public subsidy.

There’s just one catch. Lots that would be home to six households, two of them middle-income, would probably need to have bigger buildings than lots with one home on them. Without that, the numbers would all fall apart.

The numbers

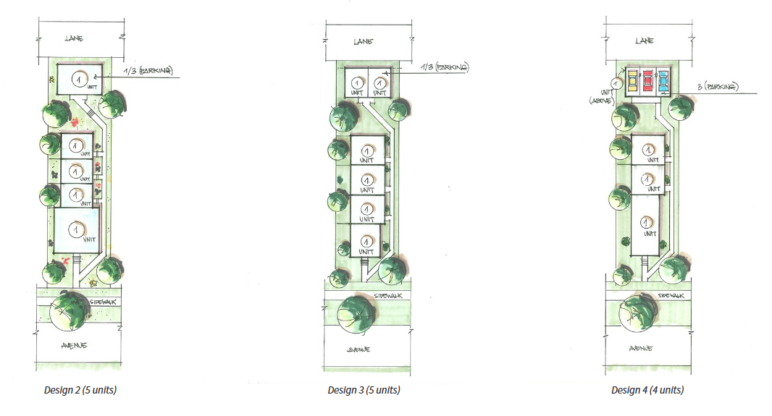

Imagining Vancouver’s six-homes-per-lot proposal. Various ways to arrange four or five homes on a standard 33′ x 122′ Vancouver lot. The rightmost design finds room for three off-street parking spaces by putting one of the four homes above a shared, alley-facing parking pad. Image from a 2019 report by Small Housing BC.

Fortunately, people like Davidson and Mussatto have been working to figure out exactly how smallplexes might work, if only Vancouver let them exist.

Last year Mussatto’s organization released a 70-page report, complete with detailed cost estimates, that seems to have become part of the basis for Stewart’s proposal. Its examples go up to five homes rather than six, and most provide one permanently below-market home on each lot rather than two.

But the basic concept is the same: attached, stacked or closely nestled homes ranging in size from 900 to 1,080 square feet each. The market-rate homes would sell for around $1 million each. The below-market homes, for around half of that.

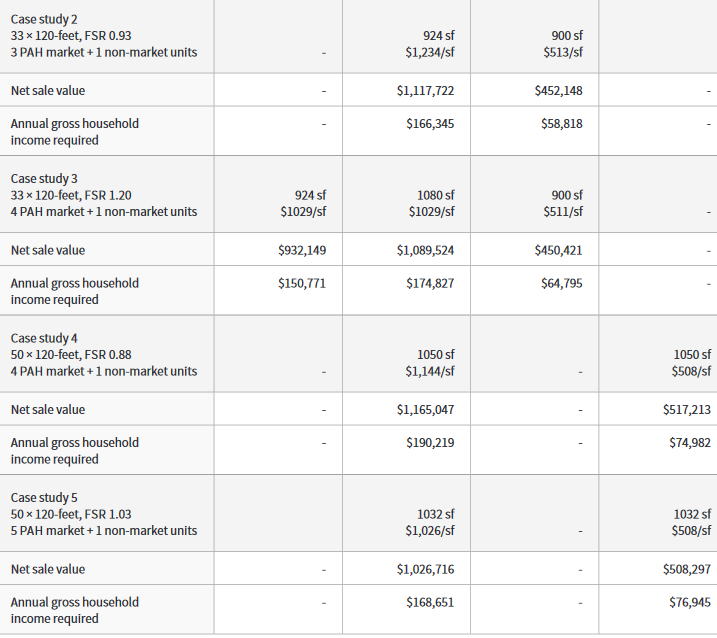

Specifications for four hypothetical smallplexes in Vancouver, with the price of one unit in each project reserved for homeownership by a middle-income household. From a 2019 report by Small Housing BC.

What about total building size? The figure to look at is “Floor Space Ratio,” which means the internal square footage of a building (adding up all its full-height floor space) divided by the size of its lot. You can see FSRs in the left column of the table above. In these examples, they range from 0.88 to 1.2.

Today, Vancouver allows duplexes on most lots, but only up to an FSR of 0.7. So if it really wants to build middle-class affordability into new buildings, Vancouver would need to raise that FSR limit and allow more housing.

For a six-unit scenario, both Mussatto and Davidson said the simplest way to arrange the units might be a market-rate fourplex at one end of a lot and a duplex, with somewhat smaller homes, at the other end.

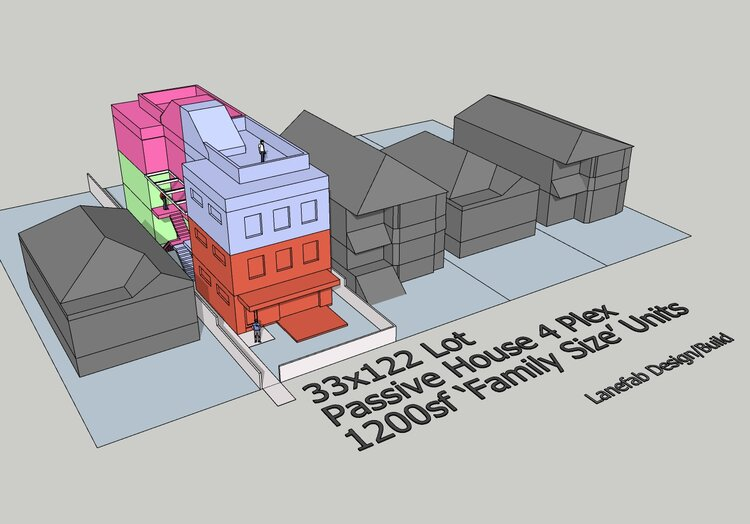

Davidson said that for Stewart’s concept to work, he’d suggest what he called a “townhouse” building size: 1.2 FSR. On one of Vancouver’s standard 33′ x 122′ lots, that’d allow 4,831 square feet of interior space. For a hypothetical fourplex, that’d allow homes averaging 1,200 square feet—three market-rate and one below-market.

“I’m always trying to target that sweet spot of unit size, somewhere between say 1,200 to 1,500 square feet,” Davidson said. For newly built homes under Vancouver’s current laws, “you can get a house that’s like 3,000 square feet or you can get a 600-square-foot condo. But getting that 1,200 to 1,500 square foot house is hard.”

Vancouver has many older houses of that size, of course. But they’re mostly detached—and far beyond most people’s price range, due to the price of empty land in modern Vancouver. So in a sense, allowing attached homes would be a way to help more Vancouverites live in more or less the same way they grew up.

Vancouver can choose: cheaper housing, or convenient parking?

Visualizing six-homes-per-lot. A rendering by Bryn Davidson’s firm, Lanefab Design/Build, of a “townhouse” style development, with a 1.2 floor size ratio and four three-bedroom homes on one standard Vancouver lot. Used with permission.

There’s one more catch: parking. No one I talked to could suggest a good way to fit more than four auto parking spaces onto a 33-foot lot with four or more homes. The only good way, they agreed, would be dedicating the alley side of a lot to parking, tucked underneath the rearmost home.

“You could get as many as four at-grade parking spaces at the rear,” Davidson said. “It’s not going to look as cutesy as a laneway house. But I think the city has over-relied on cutsiness.”

Marc Lee, a housing economist for Vancouver’s left-leaning Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, said low parking ratios would actually be consistent with modern lifestyles in Vancouver, where car owners tend to park in the street.

“No one uses their garages for cars in Vancouver,” Lee said. “That’s just storage.”

A political gambit and a longer conversation

Talking six homes per lot: Future Vancouver mayor Kennedy Stewart speaks at a 2014 event. Photo by Mark Klotz, used with permission.

Stewart’s proposal seems somewhat rhetorical. It may not find the votes on Vancouver’s city council. Stewart isn’t affiliated with any of the municipal parties, so he leads Vancouver mostly with whatever power is in his pulpit.

But this also looks like a next step in Vancouver’s unending public conversation about how to find space for its next generation of much-needed homes. If Stewart can make six homes per lot a winning issue in the 2022 election, finding the votes might not remain hard.

“It’s exciting to see the City of Vancouver bring this forward, because it does provide for more affordable ownership for many people who would never be able to do it,” Mussatto said. “The test will be, can we get the political support.”

Anger about expensive housing, segregation, and climate chaos seem to be shifting the politics of housing in North America. And the idea of re-legalizing smallplexes seems to be blowing in the wind. To Stewart’s credit, he’s listening to that.

But if this change happens, it isn’t actually going to be because of him. It’s going to be because of the people of Vancouver.

Ron Richings

I think that the central problem with this proposal is that it is rational, based on costs involved. But real estate in Vancouver is somewhat irrational, not based so much on costs as on a strange psychology. And we see that when lot density limits are increased. Land values go up, based on the profit that may result, assuming that there are buyers. This also, incidentally, results in the destruction of many perfectly fine houses, but ones that don’t maximise potential profits. So allow four or six plexes and the land values will significantly increase to the point that the assumed affordability vanishes.

Likewise the requirement for one or more ‘affordable’ units is precarious over time.

It would be trivial for a future, probably right wing, City Council to remove the affordability requirement. Voila! More profits for speculators and developers.

Given the current psychology housing and land costs will rise to absorb all of the money that buyers can put toward that purchase. Current ridiculously low mortgage rates have just fed into that. As has, over time, the commonality of multiple wage earner families. How do banks etc. frame the question? ‘How much mortgage can you afford?

‘What is the answer? Not at all sure, but many many more housing Co-ops, in the 1970 & 80s model, are likely to be part of the solution. Provides housing and security but mostly without further inflating prices.

Julie Hunter

Yes Ron: Co-ops are the answer, as are incentives to improve/upgrade currently existing houses so that their suites can be bought/run as a strata. East Van is under siege by mega developers. Your argument of upward spiralling land cost which finally will negate the initial rationalization of the concept is spot on. I don’t know why your understanding isn’t obvious to others, including the people at the top.

Julie Hunter

This saturation building is a wet dream for developers, but it’s a nightmare to current community residents/renters (It causes displacement, construction chaos, and high environmental damage, and immeasurable mental health stress) Case in point this has happened on my block: 9 people (long-terms friends, neighbours, active community members) displaced from 3 affordable rental units in an old heritage type home, garden space now gone, trees, gone, new fences that inhibit movement of city wildlife and neighbourly communication. Water permeable ground: gone. What is there? 3800 sq ft at total of $3.5 million asking, where very likely 4 high-income professionals, who are not part of our community, nor committed to it, with no family, will live.(Because no one else can afford it) Thnks but NO thanks. We need to offer home owners incentives to create suites in existing housing, and to do garage-to-studio conversions (not laneway housing, which is overbuilt for the measly square footage)

Willow West

“High income professionals, who are not part of our community, nor committed to it, with no family…” Wow, that’s quite a few assumptions you’re making, Julie Hunter, about someone just because of their income level and family demographic. I find it quite offensive, in fact. I am one of those high income professionals with no kids. Why does that automatically mean I’m not committed to my community? I happen to care very much about my community, regardless of where I live, whether it’s in a condo, where I lived previously, or in a detached home, where I live now. In fact I moved to a detached home because I wanted to have more outdoor space to work on my garden, which is how I end up talking to many of my neighbours, while at the same time beautifying my neighbourhood (the one I apparently don’t care about). Do you know which of my neighbours I have observed to care the least about our community? The rental house across the street, filled with a constant rotation of obnoxious 20-something roommates that never interact with neighbours positively, nor mow their lawn, or maintain the house, and have parties until 3am. This is the low income rental housing that people seem to cherish so much, but I would happily see that house mowed down, in exchange for a six plex, or even a mega house, basically anything owner occupied and well maintained instead of allowed to go derelict.