In June 2021, Cascadia weathered a scorching string of hundred-plus-degree days. Nearly 800 people died heat-related deaths across British Columbia, Oregon, and Washington combined. The town of Lytton, BC, burned to the ground after the temperature climbed to a record-shattering 121 degrees; streetcar cables in Portland melted; and roads in Washington cracked under the intense heat. Climate scientists found that a heat wave of such intensity would have been “virtually impossible without human-caused climate change.”

While extreme heat events like 2021’s “heat dome” are unlikely to occur annually, Cascadia’s mild climate is rapidly becoming a relic. Researchers estimate the Pacific Northwest will experience a 2021-level heat wave every five to ten years at two degrees Celsius warming, which could come as early as the 2040s, posing health and safety hazards to residents in a region with below-average levels of air conditioning. In the immediate term, making public cooling centers widely available is one way to mitigate, though not eliminate, the human cost of the next heat wave. But as more residents seek out in-home cooling solutions, electric heat pumps offer an effective solution with an added benefit: helping accelerate the region’s transition away from fossil fuels by replacing gas furnaces.

Climate change means Cascadians need cooling

Because of Cascadia’s historically mild climate, the region claims some of the lowest levels of air conditioning in North America. Among the 15 largest metro areas in the United States, Seattle ranks last in percentage of households with air conditioning; just under half of households have AC. In the Portland metro area, which has historically hotter summers than Seattle, about three-quarters of households have it. And in British Columbia, about 40 percent of households do. These rates are all lower than national averages: 91 percent of households across the United States and 61 percent of households in Canada are equipped with cooling.

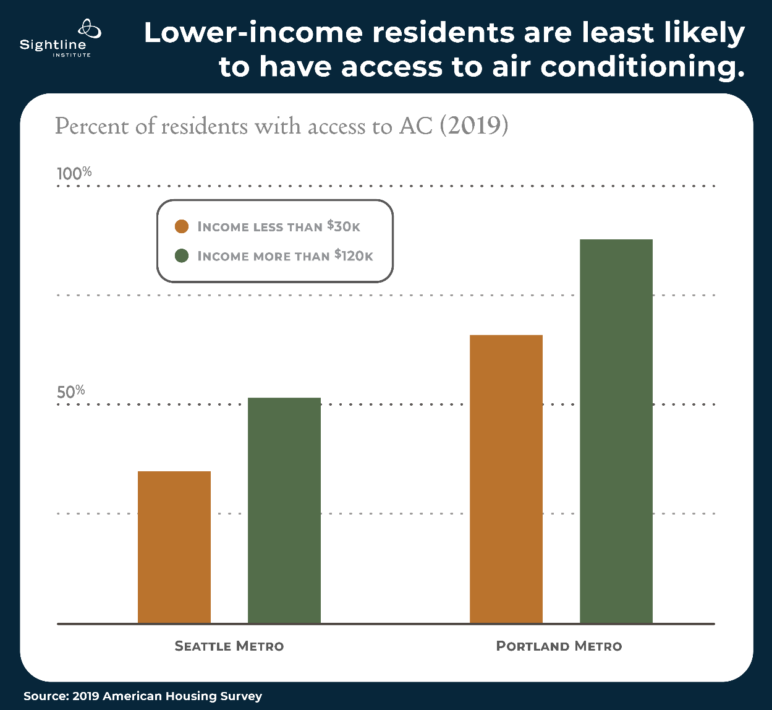

Access to cooling is unequally distributed, too, with low-income households the least likely to have it. In Seattle, the highest-income households are 17 percentage points more likely to have AC than the lowest-income households, as shown by the graph at left. The difference is 22 percentage points in the Portland metro area, as shown by the graph at right. These disparities played out across Cascadia in the 2021 heat dome, including in Multnomah County, Oregon (home to the city of Portland), where 61 percent of confirmed deaths occurred in zip codes with above-average poverty rates. In response, the Portland Housing Bureau is now requiring air conditioning in future affordable housing developments.

Heat pumps both heat and cool, while speeding decarbonization

Heat pumps warm buildings by transferring outdoor air to indoor spaces via liquid refrigerant; they cool buildings by reversing the flow of the refrigerant. When used for cooling, heat pumps are just as effective as other air conditioning units with similar efficiency ratings. Heat pumps are also twice as efficient as electric resistance heaters. Because they can both heat and cool buildings, they can replace gas-powered furnaces. They therefore offer decarbonization benefits that other air conditioning solutions do not.

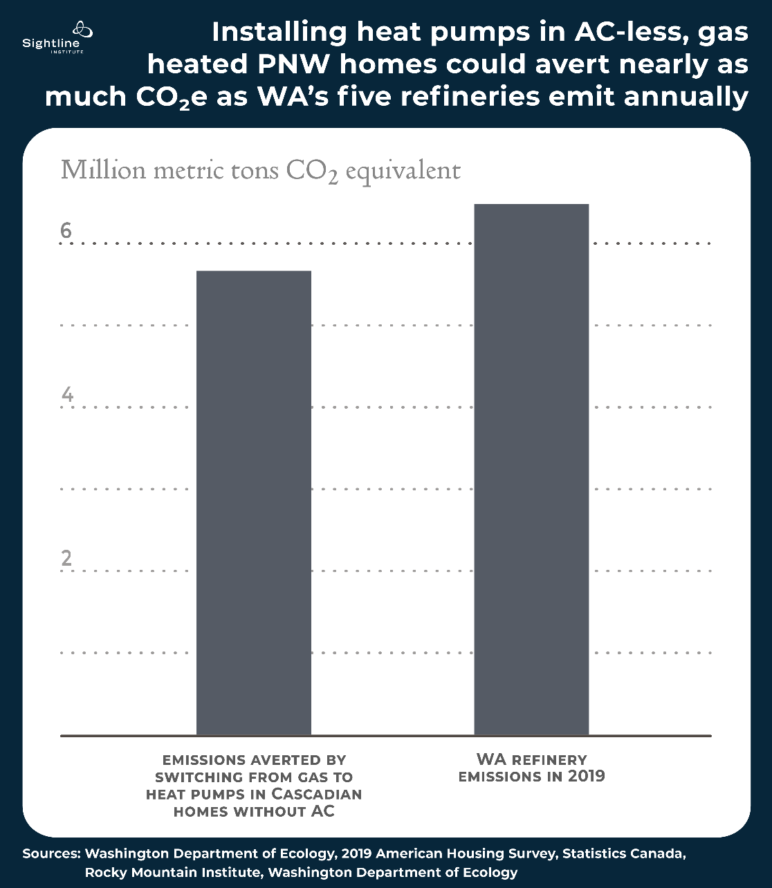

In 2019, some 38 percent of homes in the Seattle metro area used gas for heating, as did 46 percent of homes in the Portland metro area. Half of homes in British Columbia are heated with natural gas. If all gas-heated homes in Cascadia that do not currently have air conditioning could replace their furnaces with heat pumps, rather than simply installing AC units and keeping their heating source as-is, the region could avert more than 5 million metric tons of CO2 emissions annually, as shown at left below.1 This is nearly as much as the combined annual emissions of Washington’s five oil refineries, shown at right below.

Heat pump adoption is accelerating, but cost and policy remain barriers

Policy is shifting to make heat pumps more widespread. The Washington State Building Code Council recently passed the strongest energy code in the United States, requiring high-efficiency electric heat pumps in most new commercial and large multi-family buildings. The same requirement may soon go into effect for most new residential homes in the state. At the US federal level, President Biden issued an executive order in June that creates a guaranteed market for heat pump manufacturers in an effort to boost supply.

While a step in the right direction, these policies are not sufficient to ensure equal access to cooling when the next heat wave comes. Heat pumps remain prohibitively expensive for many. The average cost of heat pump installation is around $6,000 in the United States and roughly the same in Canada, though it can reach up to $35,000, depending on the type of heat pump, size of the house, and amount of labor required. Window AC units cool a smaller area but are far cheaper, costing about $500. Without policy interventions such as rebates to equalize access to heat pumps, there is a risk that only higher-income residents will be able to afford them. This would contribute to the so-called “utility death spiral,” in which fewer and fewer customers—mostly low-income residents and renters—remain hooked up to the gas infrastructure and must shoulder an increasing share of its costs, worsening inequities.

BC residents can apply for a rebate of up to Can$11,000 of the cost of converting their gas-powered heating systems to electric, and the Oregon legislature recently passed a $27 million Heat Pump Incentive Program, which includes grants and rebates for heat pump installation. Still, Oregon and Washington both lack sufficient incentives for consumers to switch from gas to electric. The Energy Trust of Oregon’s Fuel Switching Policy prohibits incentivizing customers to switch from gas to electric heating, and a bill in Washington that would have allowed public utilities to incentivize fuel switching died in the 2022 legislative session. Climate activists in Washington and Oregon have their sights set on the 2023 legislative session to again try to equalize access to clean cooling solutions.

Bracing—and building—for a new Cascadian climate

The unprecedented 2021 heat wave showed that cooling solutions are becoming a necessity, not a luxury, to live in a warming Cascadia. Heat pumps are an effective, energy-efficient cooling solution, but they remain out of reach for many, especially lower-income residents in Oregon and Washington. If policymakers are serious about both preventing future heat domes and adapting to the consequences of a warming climate, they would be smart to dramatically scale up heat pump access across the region.

Alec Billroth-MacLurg

As ASPO and Julian Darley suggested, natural gas has little geological future, and production rates will eventually, inevitably, perpetually decline. In the shorter term, as Josh Fox suggests, the externalities and the cost to freshwater and diplomatic relations, and income taxes will become more considerable to maintain or increase production rates. LNG facilities are dangerous, esp in a seismic area.

But I do not understand how this measure could help as WA’s current electricity portfolio looks depressing and underfunded. Maybe we should focus on making our current electricity needs sustainable before trying to put more loads on the grid? It seems like our eyes are on the top rung of a ladder while not paying attn to the decrepit ones at our feet. The majority comes from natural gas and hydroelectric power, facing litigation and conflicts with freshwater supplies. The Dept of Ecology projected less available freshwater in Eastern WA at the worst time as SW USA is purging their agricultural sector due to freshwater shortages and relying on practically finite aquifers. Nuclear, wind and solar PV sources are currently minute shares. solar farms are not getting the warmest welcome from places like Yakima and the embodied energy of PV equipment is questionable with Ecoinvent data.

Will we work on all rungs of the ladder at the same time? The cost of renewables will only increase as the ability to buy them will decrease by the increase of natural gas, coal, and petrol prices due to geological limitations.

I have yet to understand how taking natural gas, sending it through a pipe to the end user, and burning it there is practically less efficient than using the same gas to spin a turbine that sends electricity to a grid that travels over 100 miles to the end user. References plz? Many die from CO but many also die from electrocution.

A high initial cost at face value implies a considerable embodied energy of the equipment and installation. If the EROEI is less than 1, that’s a serious problem that one doesn’t need to compare to fossil fuels. Is there any Ecoinvent data that doesn’t suggest a conflict of interest with who is reviewing the data?

I don’t understand why yall would be comparing carbon emissions from space heating to those of petroleum refineries. Do they run directly on a petrol fuel product? How many these days?

Fred Tepfer

I really enjoy our ductless heat pump, and I understand the thinking behind this article, but I would have appreciated including a more nuanced view of the downside of heat pumps. Yes, they are extremely efficient compared to electrical resistance heating (baseboard heaters, electric furnaces, etc.). I agree with Alec Billroth-MacLurg’s excellent comment about the need to decarbonize the grid. But where ductless heat pump technology can replace electric resistance heating, especially when served by a utility with decarbonized electricity, they make sense right now.

However, there are other aspects of heat pumps should be also discussed whenever they are being proposed:

1. The refrigerant in current heat pump and refrigeration technology is an extremely potent greenhouse gas. One refrigerant leak can reverse all of the decarbonization benefits that they provide. Testing and maintenance is essential until heat pumps become available that don’t use green house gasses for their refrigerant. This problem can and will be fixed, but it hasn’t been yet.

2. Most heat pumps require more routine maintenance than many people realize. For example, the filters that protect the heat-exchanger coils need to be cleaned fairly frequently.

I thank Sightline for the article, and also wish there had been a few more paragraphs to point out that heat pumps aren’t the perfect panacea. I love them, I use them, and I also realize that they belong in second place behind simpler technologies such as passive cooling.

David K. Fisher

For “Do It Yourselfers” you can buy plug and play mini split heat pumps on line for $3,000 – $4,000. They come pre charged with refrigerant where once you have the indoor air handler mounted and outdoor heatpump compressor fan unit in place you simply push or snap in in the refrigerant lines between the two. A 30-40 amp 240 volt electrical connection is also required.

One point that has to be considered is that mini splits or any other heat pump, air conditioners will last about 15 years before they will need to be replaced. High efficiency gas furnaces last about the same and electric resistance last 30+ years.