A specter is haunting housing: the specter of mobility.

Mobile dwelling—seasonal, nomadic, occupational, or migratory—has been fairly typical for many people for much of human history. This includes the people of Cascadia: indigenous peoples, Oregon Trail colonizers, and waves of migratory workers since.

The United States and Canada have long been among the most mobile and immigrant of nations, culturally rooted in patterns of colonial and continental settlement. Yet even here the movable dweller and dwelling have widely been feared, shunned, marginalized, and zoned out.

At the center of our housing mythology, we’ve enshrined the goal of stability. Offering people stability is usually good, and our housing systems too often fail to deliver it. But we also fail to offer each other another option: mobility.

In most of the US, local law prohibits living in a vehicle, except in certified recreational vehicles in designated RV parks. Exclusionary zoning laws prohibit even semi-mobile “manufactured housing,” so-called “mobile homes,” in most US cities.

As leaders in Oregon, Washington, British Columbia, and Montana all weigh state and provincial housing reforms, a few factors should bring mobile dwelling back to the forefront of housing policy:

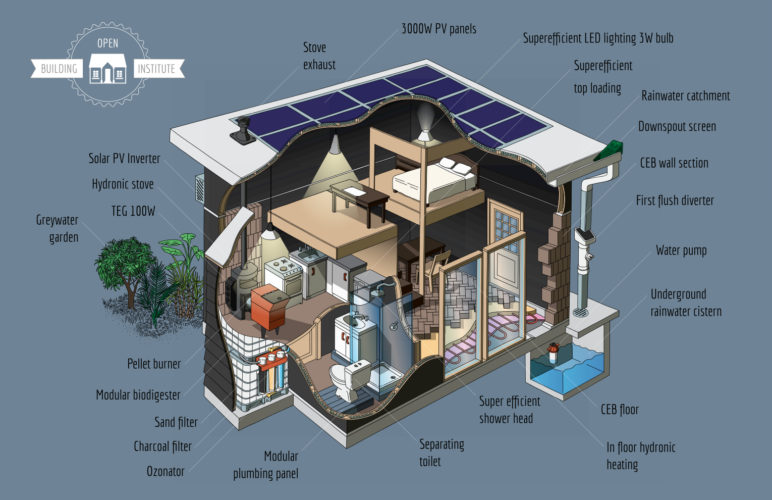

- First, in a time of accelerating home prices worldwide, small movable housing offers high adaptability and low cost: on the scale of $10,000 for construction, thanks to reduced materials, efficient off-site construction, and the possibility of building it oneself; low energy and maintenance cost, with potential for off-grid operation; and potentially low land cost due to versatility of where it can be sited.

- Secondly, big demographic shifts towards smaller and solo households.

- Thirdly, technology advances and adoption allowing many more people to work from where they choose, and RVs and tiny houses on wheels allowing for more habitable and self-sufficient options, including solar self-powering, satellite Internet, and water-efficient recycling systems: “autonomous housing.”

- Fourthly, perhaps most fundamentally, the fast-rising global unsettlement of populations due to urbanization, conflict, and climate change. Contrary to many people’s intuitions, separated or separable homes can achieve quite dense and efficient urban land use. Small movable homes can be built with adaptable, multipurpose interior spaces, and they can be two-story, joined, or stacked. They can also move to almost anywhere, like a too-large parking lot or an obsolete bit of road. And they can potentially move on, change, or expand, adapting to changing land use or their residents’ changing needs.

Open Building Institute’s ”Open Source, Modular Eco-Home” was estimated to cost $25,000 as of 2016. Image by Open Building Institute used under CC BY-SA 4.0

Just as other exclusionary zoning practices like minimum lot sizes force many people to pay for more land than they want or need, exclusion of smaller and movable homes forces many people to pay for more space and permanence than they want or need. And bans on movable homes specifically deny people having a longer-term or permanent home when their needs, wishes, and opportunities lead them to relocate.

For me these advantages loom large because I don’t have a home of my own, nor can I afford or do I particularly prefer most conventional housing. Based on my needs, preferences, and financial and work situation, I wish to build and live in a small house on a trailer, to house myself adaptably. I call it project Mendocello. But in most of the US today, I couldn’t legally live in it.

Compared to conventional, immovable housing or to RVs, such “tiny houses on wheels” (THOWs) can be not only acceptable but preferable—not for everyone, but for a portion of people, like me.

To adapt a concept from bell hooks, I see this as a form of “positive marginality”: a way that living on a margin allows a broader society and a broader self.

I want something I can afford to own, have freedom to design and build myself, and can relocate seasonally and for travel, work, and life opportunity. I take a “capabilities approach” to housing: what I want is for it to help me make the world my extended space, not to enclose more space privately for me.

Llamalopis trailer park, Las Vegas, better known locally as the Airstream park. Photo by Tiny House Expedition, used with permission.

Portland and Oregon take some steps forward, but still exclude possibilities

In the last few years, some US cities made a surprising break with the mobile-exclusionary tradition by legalizing residence in RVs or tiny houses on wheels on residential lots. First Fresno, then Los Angeles and San Jose, and various cities & states now allow mobile Accessory Dwelling Units. Portland allowed one movable home per residential lot in the 2021 Shelter to Housing Continuum zoning reforms, and Oakland created a new residential type, “Vehicular Residential Facilities,” which allows multiple vehicle dwellings on sites with sufficient area.

As Portland accessory dwelling unit (ADU) expert Kol Peterson wrote in support of the Portland reform, “RVs/THOWs…vastly exceed other housing types in terms of providing rapid, flexible, low-cost housing.”

Portland’s reform evolved from a 2017 decision by Chloe Eudaly—a maverick tenant activist turned city councilor who had been handed oversight of the city’s permitting department—to decriminalize (i.e., suspend enforcement against) vehicle dwellers on residential property. Surprisingly, even as vehicles parked on public streets drew some criticism, there was near-zero outcry over or reported issues from privately parked vehicles. Other local advocates and I were able to build upon this success and get permanent legalization. It was an unusual, exemplary case of land use reform through experimentation.

Regarding manufactured and modular/prefabricated housing, Oregon’s 2022 House Bill 4046 largely removed local governments’ ability to exclude these forms from private property. This positive step was motivated particularly by the need to replace housing destroyed by 2021 wildfires in southern Oregon. However, the legislation deliberately excluded RVs, vehicle dwellings, and most THOWs from this mandate by specifying that the permitted housing must be wider than these home types’ typical maximum width of 8.5 feet.

Also, low-cost movable/vehicle housing was advocated for and could have been enabled for “cottage cluster” housing legalized statewide by Oregon’s 2019 House Bill 2001, or in the local implementation by Portland and other cities. I observed and testified that this could allow very low-cost housing on a wide scale. It could also be an excellent housing pathway for unhoused residents because Portland’s Shelter to Housing Continuum creates an easy permitting process for outdoor shelters. These shelters could host movable THOWs, and the residents could relocate from these to low-cost cottage clusters in time, keeping and perhaps upgrading or expanding their movable homes. However, in both HB2001 rulemaking and Portland’s implementation, officials and agency staff did not seem to consider or support such approaches.

The big window of opportunity for housing reform in Oregon now, including to support less conventional forms like mobile housing, is the Oregon Housing Needs Analysis (OHNA) process. This is a major program to set state-level housing production goals, somewhat like California’s decades-old Regional Housing Needs Allocation program. In a follow-up article, I’ll offer an analysis of the just-released draft OHNA recommendations and how they might be amended to better enable new options such as low-cost mobile dwellings.

Housing options in Cascadia today increasingly leave many of us feeling priced out, hemmed in, or stuck. But they don’t have to. Some might consider mobile dwellings a chance to “light out for the Territory,” as Mark Twain wrote: vessels in which to flee from complication. But adaptive, movable housing can also help us reconsider and cultivate familiar, complicated territories inside our cities. We can open a new frontier of more affordable, adaptable urban life.

Tim McCormick (tmccormick.org, @tmccormick) is director of Housing Alternatives Network and currently loosely based in Portland, Oregon. He invites interested readers to:

- Join the public Mobile Dwelling group at groups.google.com/g/mobiledwelling;

- Follow on Twitter @mobiledwelling and @vehicleresident;

- Read, discuss, or suggest at HousingWiki’s open articles on Mobile Dwelling and OHNA;

- Attend the first national Vehicle Residency Summit, an online event November 18–19, 2022. See more information at vehicleresidency.net.

Dylan Staver

This is great if it werent for rezoning amd building more densely populated areas. Where I currently live was bought buy developers and am now forced to leave mobile home of 10 years. Sure I have taken a buy out, which I wont see untill the end of 2024. But who knows what the market will hold in store. Forgein home owner ship will be lifted. As well my monthly expenses will be double if not more that what im currently paying right now. Seems like tare down afordable housing to build unafordabel dwellings. Im happy fornthe next endeavor but am still saddened as I took pride in my mobile home, with extensive renos lots of yard work and countless displays during christmas. Its gona be sad tonjust walk away and havenbuldozers ripmot down to nothing. It was a sense of community small-town living in the middle of a city.