The Northwest seems finally poised to reap the fruits of years of hard work on climate change. Renewable energy is cheaper than fossil fuels, states and clean energy developers will soon enjoy a huge influx of federal climate dollars, and climate leaders sit at the helm of many state and local governments. But much like the proverbial kingdom that was lost for want of a nail, the Northwest states’ climate ambitions may suffer defeat over something utterly mundane: not enough high-voltage power lines.

That’s right. We may fail the climate test because we’re missing some wires.

A core strategy for decarbonizing the Northwest, as elsewhere, is to stop burning fossil fuels for electricity. Oregon and Washington both recently passed laws that require electric utilities to shift quickly away from coal and gas and toward solar and wind to generate power.1 Meeting these targets is a mammoth, and critical, undertaking. Today, the two biggest electric utilities in these states derive about half of their electricity from natural gas or coal and just ten percent from wind and solar.2

But a major problem looms. Cascadia, like the United States as a whole, suffers from a woefully underbuilt and aging electric grid. The grid is so inadequate that hundreds of proposed wind and solar projects are ending up at the back of waitlists where they may sit for years—waitlists to connect to transmission. New transmission lines (the high-voltage lines that often stretch over mountain ranges and along rivers on tall, scaffolded towers) take a decade or more to construct, giving the problem increasing urgency with each passing year.

Unless Northwest policymakers develop a plan for building out the grid we need, and unless they start erecting it immediately—through the Bonneville Power Administration, state action, utility investment, or some combination of these means—the region’s ambitious decarbonization commitments will amount to so much hot air.

Eastside solar and wind need transmission to reach westside homes and businesses

In Cascadia, the best sunlight and wind for making power are east of the Cascade mountains. Renewable projects in the region are exploding, with more than 100 wind and solar projects underway in Idaho, Montana, Oregon, and Washington. Backers have proposed dozens more, including more than 40 solar farms in Washington alone, which today houses just two.

Biglow Canyon Wind Farm by Portland General Electric used under CC BY-ND 2.0

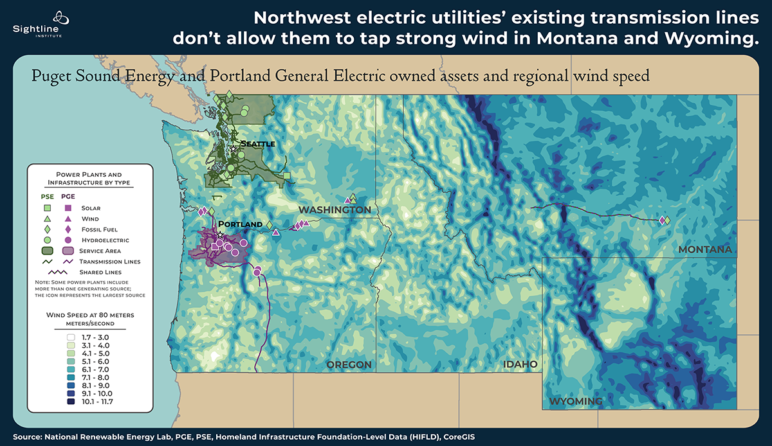

Washington and Oregon, and the electric utilities within them, are counting on tapping this eastside wind and solar to power the homes and businesses on the westside that consume most of the states’ energy. Washington’s state energy strategy, in the scenario that costs the least and electrifies the most, relies on wind from Wyoming and Montana to provide 36 percent of Washington’s clean electricity by 2050. Today, Washington derives just over 5 percent of its total electricity generation from wind power from any state. Similarly, almost all of the utility-scale wind and solar resources that Puget Sound Energy (PSE), Washington’s largest electric utility, modeled in its official, required 2021 integrated resource plan (IRP), are east of the Cascades.3

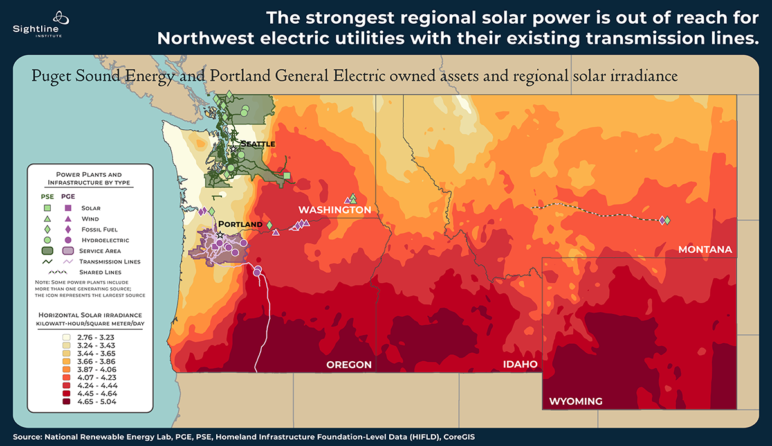

But to access this high-quality wind and sun, westside utilities like PSE in Washington and Portland General Electric (PGE) in Oregon will need to reach far outside their service territories, something they don’t need to do today because their current generating facilities, which are mostly powered by natural gas or hydroelectricity, are nearby. The maps below show PSE and PGE’s service territories, their current owned generating facilities, and their owned transmission lines. The maps also show the wind and solar potential of the Northwest. The power lines that PSE and PGE own run from generating facilities, many of which utilities will need to retire if they are powered by fossil fuels, to the cities and towns they serve on the westside. The utilities’ transmission lines barely touch the inland Northwest, with its vast wind and solar offerings.

The Northwest grid is already jammed

To bring far-away wind and solar power to their customers, PSE, PGE, and other utilities depend on the wires owned and operated by the energy and transmission behemoth in the region: the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA). BPA is a federal agency housed within the US Department of Energy that owns roughly 75 percent of high-voltage transmission lines in the Pacific Northwest, shown in purple below. Its service territory covers all of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and parts of Montana, Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, and California, as shown by the grey outline below.

The only problem? BPA’s transmission lines are basically full.

Bonneville Power Administration’s transmission lines and service territory

Transmission assets, Bonneville Power Administration, GIS map.

Every year, BPA studies the requests submitted by developers and utilities to use its transmission lines. It determines if it can accommodate the new power without overloading its grid. BPA’s 2022 study analyzed more requests for transmission than any study before it—144—up from 116 requests in 2021 and 62 requests in 2020. The 144 requests in the 2022 study alone add up to more than 11 Gigawatts (GW) of power, most of it solar and wind, that developers or utilities want to zap through BPA’s wires to the coast and other energy markets. That’s more power than the titanic, largest-in-the-United States Grand Coulee Dam generates, even at maximum capacity (almost 7 GW).

Most of the Northwest states’ glut of new wind and solar projects is idling in BPA’s transmission queue.

But without making billions of dollars of upgrades to its grid, BPA could only grant what is called “long-term firm transmission rights” to 11 of the 144 requests in this year’s study (totaling about 1 GW of power). Long-term firm transmission is the gold standard, guaranteeing a connected resource access to the grid. To ease some backlog, BPA began offering a new product, “conditional firm service,” in 2020, which still grants a resource transmission rights, but with a higher risk of curtailment.4 BPA offered conditional firm service to 96 requests (totaling about 5 GW) in its 2022 study. However, some utilities do not allow solar and wind farms with conditional firm service to bid in their requests for proposal (RFPs); advocates have been encouraging public utility commissions to require utilities to do so given the lack of long-term firm service available on BPA’s grid.

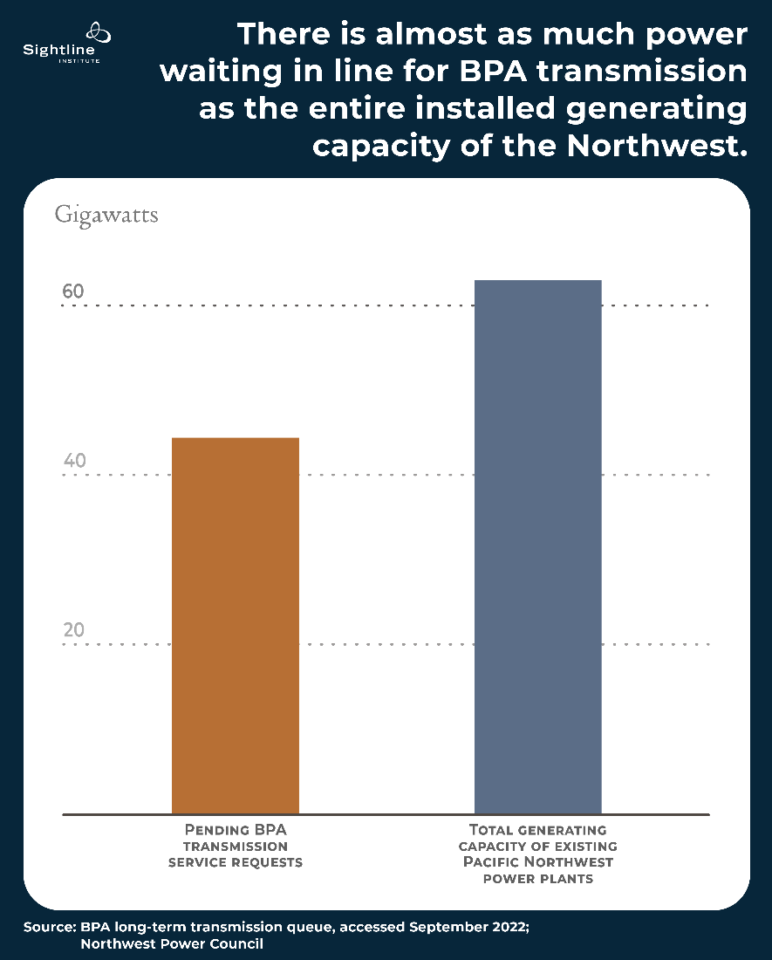

Most of the Northwest states’ glut of new wind and solar projects, in sum, is idling in BPA’s transmission queue. As of September 2022, the waitlist stretches more than 600 unique requests long, dating from as early as 2010 and totaling a staggering 44 GW of power generating capacity, as shown in the chart below at left. For context, 44 GW is almost as much as the total generating capacity of all the power plants, from hydropower dams to gas turbines, in Idaho, Montana, Oregon, and Washington combined today, shown at right below.

To be fair, not all the projects in the queue will be built; many are competing in the same utility’s RFP. Others may not be worth building. The proliferation of utility-scale renewable projects east of the Cascades has some landowners, conservationists, and Tribal Nations raising concerns. For example, some members of the Yakama Nation protest that large-scale solar development on land leased out by the Washington State Department of Natural Resources will hinder the Tribe’s treaty rights to engage in traditional gathering practices. And some Tribes that have long stewarded land that developers are now eyeing say that tribal consultation for project siting is often too-little, too-late and could repeat historical patterns of harm toward tribal communities in new energy development.

Still, there’s no question that BPA’s grid is far from prepared to handle all the wind and solar projects that Oregon and Washington need to meet their clean electricity mandates. As PSE stated in its 2021 IRP, “There is uncertainty about PSE’s ability to procure transmission for the optimal renewable resource mix.”

Groups that are often at odds with utilities are also concerned. “We often disagree with utilities on procurement, but we are pretty much eye-to-eye with them on transmission,” Spencer Gray, executive director of the Northwest & Intermountain Power Producers Coalition (NIPPC), told Sightline in an interview.

Randall Hardy, former BPA administrator, put it more bluntly, warning, “Given the transmission constraints, it’s unlikely PGE or PSE will meet their clean energy goals.”

There’s no plan and little being built

Shockingly, given how important transmission is to meeting climate goals and how backed up the grid is, neither Cascadia overall nor the individual states within it have a plan today to fix it. Fred Heutte of the NW Energy Coalition told Sightline, “If we don’t get a pretty clear view of [what we want in place by 2030] in next couple of years, we will be short on transmission.”

The closest thing to a regional transmission plan today has been developed by NorthernGrid, a membership organization of BPA and 11 utilities from Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Washington, and Wyoming.5 Regulators and agency representatives from the relevant states participate in NorthernGrid meetings as “enrolled parties,” but they have no decision-making power over the group or its plans. Since its creation in 2020, NorthernGrid has developed one ten-year regional transmission plan, in compliance with federal regulatory requirements.6 But the plan takes as its starting point individual utilities’ and BPA’s own plans, rather than working backwards from state and regional decarbonization targets and electrification scenarios. Perhaps as a result, the most recent plan included no interregional transmission projects, something numerous studies show will be critical to meeting decarbonization goals.

The five states whose utilities are represented by NorthernGrid sent a letter to the group in January 2022 saying that the most recent plan “did not sufficiently address broader states’ policies [and] priorities.” But many experts say that NorthernGrid runs a closed shop. “Oregon and Washington have been pushing to have more influence on the NorthernGrid process,” said Robin Arnold, Markets and Transmission Director of the advocacy organization Renewable Northwest.

Some improvements may be on the horizon. A subset of NorthernGrid members recently kicked off an optional 20-year planning process, and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) is considering new rules to improve regional transmission planning, including to extend the required planning horizon to 20 years, up from today’s 10. But the outcome of these efforts remains to be seen.

At the same time, transmission wire owners, particularly BPA, are hesitant to build new lines before they have guarantees that utilities or renewable developers will use them. Former BPA Administrator Randall Hardy explained that BPA is unwilling to build new lines unless they’re “already 100 percent subscribed.”

Several experts that Sightline spoke with argue that BPA should build more transmission proactively, given BPA’s dominance in the region, its recently increased $17 billion in federal borrowing authority (a move that some environmentalists and Tribes decried), and its construction experience. Spencer Gray of NIPCC told Sightline, “BPA [was] . . . the most competent transmission builder in the US for decades.” Now, Gray said, BPA has retreated to maintaining what it already has. As of this writing, BPA has no plans to build new transmission lines. Instead, it is focused on upgrades to its existing system, which are necessary, but not sufficient to meet all the anticipated new demand for transmission.

Successfully building new transmission will require early engagement with Tribes and conservationists

Part of the reluctance of BPA and utilities to build new lines may be that building transmission is controversial. Some past proposed lines sparked intense opposition, sometimes for good reason. Their sponsors struggled for years to win state and local permits and to negotiate agreements with landowners. In some instances, Tribes raised concerns over siting on or near tribal land, and conservationists objected to impacts on sensitive habitats and endangered species like the sage grouse.

In 2010, for example, PGE proposed a new 215-mile transmission line from Boardman, in eastern Oregon, to Salem, in the west of the state. Called the Cascade Crossing, it would have transferred wind and other power from eastern to western Oregon, a project the utility claimed necessary to meet its clean energy goals. However, environmental groups worried the line would be used to transport coal-generated electricity from the now-retired Boardman plant. They also argued it would disrupt national forests, and the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs objected to the original project route slated to cross their reservation. In response, PGE struck a deal with BPA to shorten and reroute the project, then canceled it in 2013.

Similarly, BPA canceled its controversial 79-mile I-5 Corridor Reinforcement project nearly nine years after it proposed the line, as costs and local opposition mounted. In a 2017 letter explaining the cancellation, then-BPA Administrator Elliot Mainzer wrote, “BPA will seek first to use efficiencies and build at the smallest scale possible to meet our customers’ needs” before acknowledging that “the region inevitably will need to build new lines.”

All this is to say that transmission line sponsors need to take seriously the burden of new infrastructure on communities, especially Tribal Nations that have been harmed by prior purportedly clean energy projects like hydroelectric dams. Many advocates rightly emphasize building the fewest new lines possible by investing in energy efficiency, maximizing the capacity of the existing grid, dramatically expanding distributed resources like rooftop solar and battery storage, and ramping up “demand response” programs to encourage consumers to shift electricity usage during times of peak demand. Oregon and Washington could generate 34 percent and 27 percent of their electricity respectively from rooftop solar, according to a 2016 study by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. But even if all these efforts are successful, the need for new lines cannot be completely eliminated.

Today, the biggest new transmission project in the region is PacifiCorp and Idaho Power’s 300-mile Boardman-to-Hemingway line, which intends to bring renewable power from the Intermountain West to the Pacific Northwest and is not without controversy. Its expected completion date is currently 2026, a full 20 years after backers originally proposed it.

The site of the proposed Boardman to Hemingway Transmission Line Project in Baker County, Oregon. Image by Northwest Public Broadcasting

Northwest policymakers need to get in the driver’s seat

In the Pacific Northwest, policymakers increasingly recognize the looming problem of transmission shortages. Washington’s 2021 Clean Energy Transformation Act created a taskforce to identify transmission constraints and needs in the state, and the Oregon Legislature funded a 2021 study assessing whether Oregon should join a regional transmission organization, a plan some advocates argue would improve transmission planning and operations in the region.

While these developments are positive, policymakers and regulators in the Northwest still largely sit on the sidelines of transmission planning. It’s not surprising: Northwest states have no authority over BPA; transmission is exhaustingly arcane and technical; and the Northwest’s electric utilities, unlike those in other regions, continue to be vertically integrated monopolies. They often remain powers unto themselves. (There’s an old joke in Idaho politics that the state is named for the power company Idaho Power, not the other way around.)

Leaders in the Northwest can no longer afford to yield the field on transmission.

But leaders in the Northwest can no longer afford to yield the field on transmission. A start would be creating a 20-year transmission plan for the region designed around decarbonization goals, anticipated increases in electricity demand, the location of renewable resources, Tribal treaty rights, and environmental protection for sensitive habitats. The plan could build from the one underway by some NorthernGrid members, or states could develop it away from the influence of utilities, much as the Northwest Power Council does for regional resource planning through its Northwest Power Plan. To support a planning process, Northwest leaders may be able to leverage some of the $100 million allocated by the new US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) to convene stakeholders on interregional and offshore transmission capacity.

Once a plan exists, Northwest policymakers need to do everything in their power to start building. One option is for the Northwest Congressional Delegation, which several experts say functions as BPA’s unofficial board of directors, to pressure BPA to take more risk and break ground on new lines before they are fully subscribed by utilities or renewable developers.

Another option is for Northwest states to build and finance new wires themselves, learning from the experience of others. For example, in 2005, the Texas legislature directed the Public Utility Commission of Texas to develop a transmission plan to carry wind resources in the western part of the state to customers in the eastern part of the state. Transmission service providers built 3,600 miles of transmission lines, enabling 18.5 GW of additional wind power to connect to the grid. The expansion was expensive—it cost Texas ratepayers almost $7 billion—but it tripled the amount of wind capacity in the state. As of 2020, Texas generated more wind power than the next three highest states combined.

Other examples Northwest policymakers might explore include Colorado’s recently created Electric Transmission Authority or New Mexico’s Renewable Energy Transmission Authority, which has built new wires paid for not by ratepayers but by wind farm developers. To finance new projects, Northwest states could leverage the $2.5 billion revolving fund for transmission in the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act or the $2 billion in loans designated for transmission projects in the IRA.

Clean electricity hangs in the balance

Cascadia’s climate aspirations depend on whether the region can buck the trend of recent history and rapidly upgrade and expand its electric grid. Hundreds of renewable energy projects are ready and waiting, but without a bigger grid, they will never get built. The region’s clean energy goals hang in the balance. Leaders in the Northwest can no longer relegate the all-important task of transmission planning solely to BPA or electric utilities. It’s time for policymakers and regulators to wade into arcane transmission planning processes. They can up the pressure on the usual suspects to start building more. Or Northwest leaders can take matters into their own hands.

Either way, though, decarbonization requires a lot more wires.

Kristi Lynett

Great piece! Thanks for the clearly described research and recommendations.

Scott Walker

Excellent expose’. Decarbonizing IS essential. But as a long time student of Sightline education, I have to call BS on the foundational premise that we must get more transmission. Though it is hardly discussed, we can decarbonize and make dramatic, I mean HUGE, reductions in future energy needs. It’s a matter of eliminating the 1/2 of all car trips that are less than a few miles by investing in walking, biking, and transit while simultaneously eliminating the subsidy for driving provided by free and excessive parking.

If Portland or Vancouver, BC can do it, the rest of Cascadia can too. Otherwise, we are looking at a future of more cars and more solar and wind farms instead of a sustainable future.

Scott Walker

An adendum: I missed making the connection for the supposed and perceived need for more transmission capacity is to supply power for the supposed essential transition to EV’s. Though a marginally good thing for essential services, the whole push to transition to EV’s is driving the false premise.

Lukas Gessner

Thank you for making this point! Though much work remains to be done to decarbonize the PNW’s grid, the truth is that this region already has one of the greenest energy supply systems in the country. Let’s not squander that advantage by feeding what green power we already have into our wasteful transportation systems and urban forms! Transportation is already the plurality emitter of CO2 in the region, and given the slow adoption of EVs, in any case, we’re putting the cart before the horse hoping that speeding that particular process up will make a big difference.

Get people out of their cars–and build neighborhoods that don’t more-or-less require that they own one–and you get two birds with one stone: more green power goes to housing, industry, etc., and cut our transportation CO2 emissions…all while saving PNWers money on transportation expenditures!

David Johns

Saving energy and decarbonizing always seems to involve using more energy and more carbon. Mining metal for pylons and wires is an example. We need to address the drivers of energy use–more people and more economic activity. Let’s reduce our population drastically and dump our toys.

Karen Bray

Great article regarding out Transmission Lines. Question? We have solar panels on our home which supply all the energy we need to drive our EV and heat and cool our home(electric heat pump). We send more energy back to the grid than we use in a year. We are considering installing storage batteries,but know their construction is very energy intensive. Any suggestions?

Mathieu Federspiel

Transmission problems and costs over the long distances Moore writes about may encourage more local power generation, like rooftop solar and smaller wind turbines in residential/business districts. Energy farms (solar and wind) have all sorts of problems, such as converting land from nature, bird and bat kills, disrupting animal migration patterns, etc. Smaller, local installations that generate power closer to where it is used, on land that is already disrupted, would help a lot, and would reduce/eliminate the need for long-distance energy distribution, which is also more susceptible to sabotage.

John M. Endres

In 2017, the proposed PacWest/HiTest silicon smelter in Newport, Washington, was touted as a “green” facility since about 5% of its “metallurgical grade silicon” product would be further refined for use in silicon solar panels.

Silicon smelters have tremendous electricity demands and are highly polluting heavy industrial facilities that burn Coal, Charcoal, and Wood Chips. The estimated annual emissions would include over 766,000 tons of greenhouse gases per year, plus tens to hundreds of tons of other coal toxins per year.

My investigation into scientific papers describing solar panel carbon footprint calculation methods revealed some surprising and concerning issues:

(1.) Reported carbon footprint values of silicon solar panels found in reviewed literature do NOT include the silicon smelting process, which is perplexing since silicon is the critical component of silicon solar panels.

(2.) Carbon footprint calculations use a process known as Life Cycle Assessment and Life Cycle Inventory. These methods are highly subjective, yield inconsistent and non-comparable results, are not governed by a standard unifying method, and are typically performed by industry instead of independent bodies.

(3.) According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), greenhouse gas emissions from biomass sources (wood chips, charcoal, etc.) are not accounted for at the point of combustion in energy and industrial sectors, including smelting. But we all know that burning wood and charcoal emits smoke (carbon dioxide and other gases). A number of reviewed papers challenge the IPCC’s biomass accounting method.

(4.) The carbon dioxide sink loss due to the harvest of trees for wood chips and charcoal used in the smelting process is not included in silicon solar panel carbon footprints. It can take decades to more than 100 years to replace the carbon dioxide sink loss due to tree harvest.

Using the provided raw material and emissions quantities for the proposed smelter, “The Impact of Silicon Smelting on Crystal Silicon Solar Panel Carbon Footprints” was estimated and suggests that silicon solar panels account for more atmospheric carbon dioxide than they save.

Excluding the silicon smelting process from solar panel carbon footprint calculations undermines the integrity of the silicon solar panel industry, and challenges the “green” claim of the proposed silicon smelter, and the “green” claim of silicon solar panels as well.

We are facing a climate change crisis. If we do not approach the environmental impacts of our activities with the utmost integrity and transparency, we will face ever increasing challenges to our quality of life.