Cascadian states, especially Oregon and Washington, are US leaders in promoting voter turnout. They pioneered automatic voter registration and voting by mail, for example, and their voter turnout numbers are admirable. But Washington lags Oregon in one major way: many of its local elections have dismal turnout.

Take King County, Washington, which encompasses the heart of the greater Seattle area and is the most populous county in all of Cascadia, with 2.2 million residents. King County is, first of all, big. It’s got more residents than Idaho. It’s more than two Montanas or three Alaskas. Its county government, overseen by the elected County Executive, is also big, with a budget in the same range as these states. Its Elections Director oversees the largest election operations and ballot-counting center in the Northwest by a large margin. And King County Council members represent districts with far more residents than state legislators anywhere in Cascadia.

A trivial-sounding proposal to amend King County’s charter is the hidden blockbuster of next month’s county general election.

But King County’s voter turnout in elections for these posts is much lower than is turnout for state positions in any Cascadian states. Measured as a percentage of registered voters, it is often stuck in the 40s, while state positions across the region get turnout in the 60s or 70s. In fact, King County’s turnout is routinely 25 to 30 percentage points lower than turnout in Oregon for county elections. Oregonians are not more virtuous; their state just holds county elections at the same time as state and federal ones, in even years, when people have many more reasons to vote.

All of which explains why a trivial-sounding proposal to amend King County’s charter is actually the hidden blockbuster of next month’s county general election. By approving the measure, voters can move county elections from odd years to even years and, through this simple step, boost voter participation in county races by perhaps half or more. In short, they can move the election to when the voters are. By doing so, they can also engage an electorate that better represents the county—one that no longer overrepresents older voters, white voters, and homeowners. And they can inject fresh energy into a movement to win the same salutary rescheduling for city elections statewide, with similarly outsized benefits for representation.

Odd year out: We vote when the stakes are high

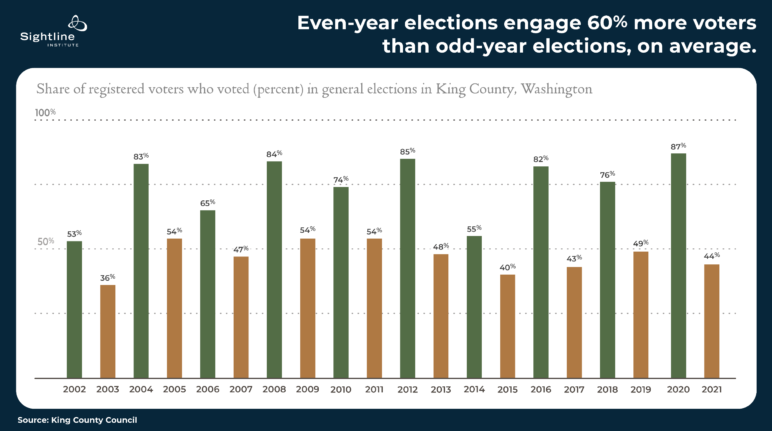

Over the last two decades, an average of 74 percent of registered King County voters cast ballots in even-year elections, voting in the mid-80s in presidential years and less in midterms, according to King County Elections data assembled by County Council staff. In odd years, only 47 percent typically voted. The high-stakes races in even years boosted turnout on average by more than 27 percentage points, an almost 60 percent increase. Lower-stakes odd-year elections draw less turnout. Off-season primary and special elections, when the stakes are lower still, sometimes only attract ballots from 20 percent of voters. (In Washington, state law allows as many as four elections a year, and five in presidential years, including slots for ballot questions such as school levies in February.)

Over the last two decades, an average of 74 percent of registered King County voters cast ballots in even-year elections, voting in the mid-80s in presidential years and less in midterms, according to King County Elections data assembled by County Council staff. In odd years, only 47 percent typically voted. The high-stakes races in even years boosted turnout on average by more than 27 percentage points, an almost 60 percent increase. Lower-stakes odd-year elections draw less turnout. Off-season primary and special elections, when the stakes are lower still, sometimes only attract ballots from 20 percent of voters. (In Washington, state law allows as many as four elections a year, and five in presidential years, including slots for ballot questions such as school levies in February.)

“Nationwide, local voter turnout generally doubles when elections move from off-cycle to on-cycle contests.” –Zoltan L. Hajnal, PhD, elections scholar, UCSD

King County’s voting ratios are consistent with academic research on the subject. Writes Zoltan L. Hajnal of the University of California, San Diego, “Every one of the eight published studies on local election timing finds that moving to even year elections (often called on-cycle elections) is by far the biggest thing that localities can do to increase turnout. Nationwide, local voter turnout generally doubles when elections move from off-cycle to on-cycle contests.” That’s a remarkable finding, considering that get-out-the-vote and registration drives are lucky to boost participation by a percentage point or two.

Even-year elections engage more-representative electorates

In Seattle, which has one-third of King County’s population, odd-year voter turnout dips, especially for voters of color and young voters. That is, Seattle’s odd-year electorate is much older and whiter than the population. Consequently, it overrepresents homeowners and high-income households.

Seattle’s odd-year electorate is much older and whiter than the population. Consequently, it overrepresents homeowners and high-income households.

The same pattern is evident across Washington: since 2000, only 18 percent of voters under the age of 25 participated in odd-year local elections. They made up just 3 percent of the electorate—one-quarter their share of the voting-age population. In even-year elections, their turnout rate almost tripled to 50 percent.

The pattern holds across the United States, according to Hajnal: “[O]lder voters (those aged 65 or older) tend to dominate odd year contests. In odd year elections around the country, working class Americans, racial and ethnic minorities, and other disadvantaged groups are . . . underrepresented.”

Writing elsewhere with Vladimir Kogan of Ohio State University and Agustin Markarian of University of California, San Diego, Hajnal notes, “Whites . . . are almost twice as likely as Latinos and Asian Americans to participate in local contests. The imbalance by education, income, and age is just as stark.”

Skewing the electorate has consequences for democracy. A national study found that localities with high-turnout elections elected far more city councilors of color than did localities with low-turnout elections. Researchers Michael Harney and Sam Hayes compared school board members’ views with their constituents’ and found that school boards elected in even years matched public sentiments better than did boards elected in odd years.

Sure, more people will vote, but will they vote for local offices?

One objection to even-year elections is the claim that long ballots are overwhelming. Voters may mark their choices for president and governor but leave blank the local races at the bottom of the ballot.

It’s a reasonable concern, but it’s mistaken. The differences in voting that long ballots cause to races at the bottom of ballot, called “down-ballot drop-off,” are small compared with the massive increases in voting brought by even-year elections, as two examples illustrate.

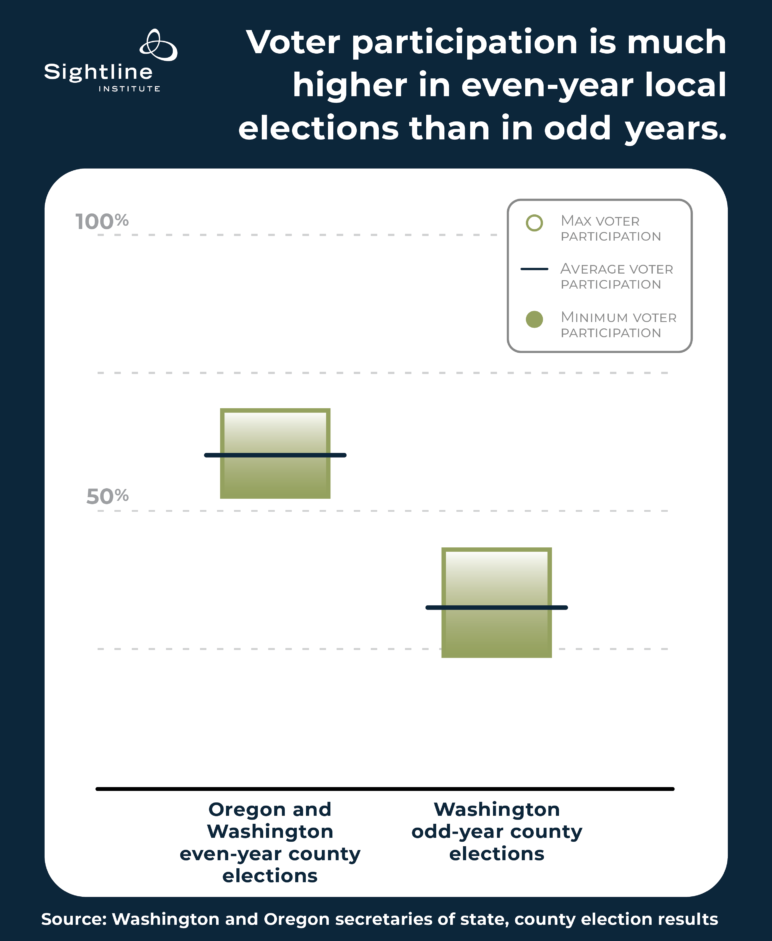

- In 2019, my then-colleague Kristin Eberhard compared contested, odd-year county races in Washington with contested, even-year county races in Oregon and Washington. She found that participation averaged 60 percent in the local even-year contests (buried at the bottom of long ballots) and 33 percent in the odd-year ones (prominent at the top of short ballots). (See figure below; data here.)

- King County does run elections for judges and prosecutor in even years, and these races routinely draw more voters than do elections for county executive and county councilors in odd years, even though the latter positions are more influential than the former. Indeed, in November 2020, 85 percent of county voters filled in their ballots on seven county charter amendments, answering Yes or No to uninspiring, far-down-the-ballots questions such as whether the county executive should have responsibility for bargaining over working conditions with employees of the county’s public safety department. The following year, only 43 percent of voters cast ballots for county executive, the top job in the county and the person who oversees a budget of almost $8 billion a year.

Down-ballot drop-off is not an issue, but odd-year elections are.

Consolidate elections in even years

Oregon, Idaho, Montana, and 36 of 39 Washington counties hold county elections in even years. All of them benefit from much higher turnout.

Shifting elections to even years would be just as good for other localities as for King County. Already, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, and 36 of 39 Washington counties hold county elections in even years. All of them benefit from much higher turnout.

The weak spots in Cascadian turnout are at the county and city levels of government. At the county level, three Washington counties—King, Snohomish, and Whatcom—vote in odd years, and Alaska’s alternative to counties, which are called “boroughs,” vote at unusual, off-cycle times, such as October of even years. At the city level, not only Washington but also Idaho and Montana run elections in odd years, and Alaska runs them in unusual, off-cycle times too.

A century ago, the Progressive movement, intent on breaking American cities’ “political machines,” succeeded in disconnecting local elections from state and national ones by shunting them to odd years. Along the way, they also unintentionally boosted the local power of older, whiter, richer, homeowning, native-born citizens. The system stuck, and to this day almost 80 percent of US municipalities hold their elections in odd years or otherwise off-cycle.

But change is afoot.

Oregon has long since consolidated its county and city elections in even years, in sync with state and federal elections in November, lifting turnout.

In 2015, California adopted a law to move elections to November of even years in every locality where turnout in off-cycle elections lagged 25 percentage points or more behind on-cycle elections. In the months that followed, some 54 cities across the state revised their codes and phased in the new schedule. That’s 11 percent of the state’s cities. In these cities, turnout has tripled, on average, as a result. In 2020, unfortunately, a California state court exempted from the law all the cities—generally the large ones—that have their own home-rule charters. Such charter cities make up a quarter, or 121, of the state’s 482 cities.

Separately, though, some California charter cities are switching anyway. Los Angeles shifted to even-year elections in 2015. Angelenos adopted the calendar change at the ballot with a 72 percent “yes” vote, and other California home-rule charter cities have done the same by similarly lopsided margins: 83 percent in Glendale in 2018, for example, and 81 percent in Burbank and San Mateo. San Francisco voters will decide next month whether to join the trend and move to the evens.

In 2018, Arizona approved a similar law, and in 2019, Nevada followed suit. Both explicitly included cities with home-rule charters. Meanwhile over the years, a steady stream of US localities flipped to even on their own, including Austin and El Paso, Texas; Sarasota and many other Florida cities; Trenton and other New Jersey cities; Baltimore, Maryland; Raleigh, North Carolina; and Santa Fe, New Mexico.

In the 2022 Washington legislative session, Rep. Mia Gregerson (D–SeaTac) and nine colleagues co-sponsored a bill to move city elections off of the odd years. Outdoing the ambition of other states’ laws, the measure does not fiddle with thresholds of low turnouts to trigger a change. It simply eliminates odd-year elections entirely. It strikes them from the menu of options available in the state to all levels of government. Not only would off-cycle city and county elections disappear, so would ballot initiatives in low-turnout years.

Such a dramatic simplification of the state’s election code would lift voter participation and improve representation in local elections statewide. It would catch Washington up with Oregon as a leader in voter turnout, and it would leapfrog the Evergreen State beyond California.

But before the legislature in Olympia reconvenes in early 2023 and again takes up the Gregerson bill, King County voters—who are almost 30 percent of voters in the state—can show the legislature what to do by approving the hidden blockbuster on the November ballot, charter amendment 1. It’s a deceptively simple measure that promises to boost turnout by more than half, just by rescheduling county elections.

Greg

You equate voter turnout with voter quality. I would argue that quality of votes down ballot diminish with the more items on the ballot. I like odd-year elections for our local representatives (I’m in Spokane) because it gives me an opportunity to focus on those candidates without all of the noise of the other elections that are occurring. This becomes more important in non-partisan races such as city councils.

The article states, “Odd-year, off-cycle city elections suppress turnout, just as odd-cycle county elections do.” While I can certainly see that occurring in states that require in-person voting, I don’t see how that applies to vote by mail states like Washington. Does it reduce participation? Sure, but that’s on the voter not the fact that higher profile elections aren’t on the ballot. That shows that a large number of voters are not overly interested in local elections.

I would like to see voter participation increase as I consider it our right and civic duty to participate in elections. I like Washington’s vote by mail system and encourage everyone to vote. I do hope they will be informed voters though and the more items on the ballot make it less likely that that will occur.

Alan Durning

Thanks for your comment, Greg. What evidence convinces you that, “quality of votes down ballot diminish with the more items on the ballot”?

Greg

I don’t have any evidence or studies to back that up, just personal experience in my own voting habits and talking with others. I don’t know if there have been any studies that show whether or not voter knowledge is impacted as the number of items on a ballot is increased. It would seem that would be the case, but that’s based on my own opinion.

It would seem that as the number of races and ballot measures are added to a ballot, the more likely that knowledge of each specific item would decline as individuals would be more aware of some items over others. The voters guide certainly helps and the opportunity to vote by mail is invaluable in improving the opportunity to better understand the issues and the races prior to voting. It just seems that down ballot issues would take less priority than top of ballot issues.

It would be great if I’m wrong about my theory but what I’ve experienced in talking with others seems to support my theory. That’s far from scientific though.

asdf2

Be careful what you wish for. If elections for municipal candidates are moved from odd numbered years to even numbered years, it will mean even lower turnout for ballot measures in odd numbered years. This means more Tim Eyman initiatives passing and emergency transit funding measures less likely to pass.

Alan Durning

Perhaps you didn’t read all the way through? I wrote, in the third paragraph from the end,

“In the 2022 Washington legislative session, Rep. Mia Gregerson (D–SeaTac) and nine colleagues co-sponsored a bill to move city elections off of the odd years. Outdoing the ambition of other states’ laws, the measure does not fiddle with thresholds of low turnouts to trigger a change. It simply eliminates odd-year elections entirely. It strikes them from the menu of options available in the state to all levels of government. Not only would off-cycle city and county elections disappear, so would ballot initiatives in low-turnout years.”

John Abbotts

Thanks, Alan,

For this post, and for your comments in other posts on RCV. For those advocating the “quality” of votes, readers need to be reminded that this is an excuse that MAGA Republicans use to suppress and subvert voters, and old segs used to suppress votes from people of color.

Not accusing anyone above of that, just sayin’

All stay safe, from election denial and other “alternative facts”

Alec

I voted against this measure. Now that I read this article, which is more comprehensive than King County’s own report, evenyears.org, and another article on Sightline which just read “it isn’t rocket science”, I probably would’ve just skipped voting on this if I had another chance. Thank You Kristin and Alan for getting together a more appropriate study which actually suggests turnout for countywide decisions would increase by observing trends from areas that already did this.

But it still seems counterintuitive for the demographic of voters who are too poor to make that much time to vote and I have no clue how Zoltan could claim rescheduling is better than mandatory PTO for every primary and general for increasing turnout. His study from this year that Alan cites didn’t observe what Zoltan called “rolloff” based on income, but he did observe a considerable rolloff trend with younger voters, and none of his prior observations addressed the whole point of rescheduling local contests.

So many local to international studies and observations suggest a correlate of a stronger social safety net to voter turnout.

Kim Quailie Hill, Jan Leighley “The Policy Consequences of Class Bias in State Electorates” 1992

Dennis Mueller, Thomas Stratmann “The economic effects of democratic participation” 2003

Paul Martin “Voting’s Rewards: Voter Turnout, Attentive Publics, and Congressional Allocation of Federal Money” 2003

James Avery, Mark Peffley “Voter Registration Requirements, Voter Turnout, and Welfare Eligibility Policy: Class Bias Matters” 2005

Valentino Larcenese “Voting over redistribution and the size of the welfare state: the role of turnout” 2007

Vincent Mahler “Electoral turnout and state redistribution: a cross-national study of 14 developed countries”2015

James Avery “Does Who Votes Matter? Income Bias in Voter Turnout and Economic Inequality in the American States

from 1980 to 2010”

2015

Navid Sabet “Turning out for redistribution: the effect of voter turnout on top marginal tax rates” 2016

Ioannis Theodossiou, Alexandra Zangelidis “Inequality and participative democracy: a self-reinforcing mechanism” 2020

Katie Wilson “How poverty hurts Washington State’s democracy” 2020

And Census Bureau ACS data during federal election years has repeatedly correlated income to voter registration and turnout. The data from 2020 did see a decreased low-income American response of something like “I was too busy to vote”. States like NY and KY did allow no-excuse absentee voting for that one pandemic year. But when someone has little to no opportunity to look into why a race is important, they can lie to themselves or bias their perception to feel better about their situation, and maybe give the Census Bureau a response like “Did not like any of the candidates”. When NY went back to the old way and required a reason for getting an absentee ballot, they flipped a bunch of US House seats this week.