My family lives in fire country in Idaho, Montana, and Washington. A new era of megafires that no amount of firefighting can control is forcing all of us across Cascadia to learn a new way to live with fire. Wildfires have become more frequent, larger in acreage, and more severe,1 and the risk they pose to those in their path is predicted to increase two- to sixfold in most areas of the West.

More firefighting is not the answer. What my family has discovered, and what wildfire scientist Jack Cohen has been saying for years, is that we cannot avoid extreme wildfires, but we can avoid devastating damages.

This fall, my mother, with guidance and financial assistance from the Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation (MDNRC), is pruning or removing flammable trees and brush near her home and regularly watering the lawn. Taking these and other measures to keep flames away from homes, schools, and businesses is commonly called “creating defensible space.” She also plans to cover her vents with ⅛-inch metal mesh screens and caulk any gaps where embers could enter the home and ignite it from the inside. Thankfully she already has a metal roof. Her actions toward making the structure itself fire-resistant are referred to as “home hardening.”2 In this and subsequent related articles, I will refer to home hardening and creating defensible space together as “fire hardening.” Short of living in a concrete bunker, we can’t guarantee that our homes will survive a wildfire, but fire hardening them dramatically improves the odds.

Sleeping bundles lent to Lytton fire evacuees, at Shxwhá:y Village Long House in Chilliwack, British Columbia. Credit: Amy Romer, used with permission.

Fire hardening homes and communities is a cornerstone of climate resilience and adaptation. The question is, how can we make it a new norm? The first step is redefining wildland-urban fire as a home ignition problem, not as a problem of controlling wildfires. Aside from changing how fire is portrayed in the media (ahem, journalists!), shifting funding from suppression to fire hardening would cue this shift in our collective understanding. These funds could pay fire hardening professionals to provide services such as reroofing, covering vents, tree removal, and yard maintenance to homeowners in fire country or reimburse these homeowners’ fire hardening expenses through grants and tax breaks.

Another step is overcoming some serious market disincentives that prevent developers from building fire-resistant communities and that keep homeowners from fire hardening their existing homes. But adopting and enforcing mandatory wildfire building codes may be the most effective way to overcome market disincentives and to etch the home-hardening norm into our collective consciousness.

This is the first article in a short series on adapting to our new wildfire normal. These articles will investigate two cornerstones of living with wildfires: creating fire-adapted communities and returning “good fire” to the land.

Extreme wildfire conditions are here to stay

Of all the forest fires that ignite in the United States, 97 percent are put out on initial attack. But the 3 percent of fires that escape often grow to more than 100,000 acres, qualifying as “megafires.” There will be more of these large fires that are impossible to stop until the rains come or the wind changes, no matter how many forest patches managers attempt to thin, how many bulldozers push control lines, or how many airtankers dump thousands of gallons of water, each flight-hour costing tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars, in their attempts to extinguish the blaze.

Wildfire suppression expenditures in the United States have increased twentyfold over the past 35 years, hitting $4.5 billion in 2021. Yet community losses continue to rise. When health and productivity costs are included, California’s 2018 fire season cost the US economy some $149 billion. That’s 0.7 percent of US GDP.

In the wildland-urban interface (WUI), which describes the transition zone between unpeopled areas and developed areas, new homes are going up faster than in any other land type in the United States. This means more potential fire damage and more fires: almost 9 out of 10 wildland fires are caused by people—power lines, equipment, fireworks, campfires, arson, and more.

Unfortunately for our lungs, Cascadia will have to learn to live with more smoke and extreme wildfires. It is unrealistic to think that we can return to what’s commonly perceived as a “normal” fire regime, one without regular wildfires and smoke.

It turns out that the Northwest historically had a hotter and drier climate than what was experienced from the 1950s through the 1980s. Those were unusually cool and wet years, leading to fewer fires and fires that were easier to put out. This means that present-day forests are getting hotter and drier weather from two separate causes: both from a natural return to historical pre-1950s climate conditions and also from human-caused climate change. Add on top of that the buildup of forest fuels over a century of fire suppression, and it’s clear that a more smoke- and fire-filled future is unavoidable.

But we can prepare for this future. If we want to bend the curve of escalating costs and community losses, Cascadians need to fire harden their homes and communities.

Suppression alone is not the solution

Airplane delivering fire retardant. Source: Oregon Department of Forestry, public domain.

Unquestionably, firefighting resources are an invaluable tool, especially when the air is crackling dry and winds are howling. The problem, according to Derek Churchill, Forest Health Scientist for the Washington Department of Natural Resources, is that “suppression alone is just kicking the can down the road; it’s not a long-term solution.”

Suppression, it turns out, is part of the problem. Unsustainable public expenditures are just the beginning. A century of fire suppression is part of what got us into this dilemma. Churchill explains how fire can clean out tinderbox forest fuels. “In 2021 the Cedar Creek Fire threatened communities in the Methow Valley but now provides some protection,” he said. “The best place to stop a fire is the perimeter of a past fire.”

“It’s misguided to measure the devastation of wildfire in terms of acres burned, as the media typically do.”

And many forests need regular fire to stay healthy. For most lands east of the Cascades, forests evolved to depend on regular fire. So it’s misguided to measure the devastation of wildfire in terms of acres burned, as the media typically do. The footprint of most fires contains lightly, moderately, severely, and unburned forests, all of which can serve different ecological functions.

Fires are catastrophic only when humans are in their path.

How to create fire-adapted communities

Unhardened home (left) compared with a hardened home (right) inside an experimental wind tunnel. Source: (IBHS, 2019).

The best available science suggests that by fire hardening a home and its surrounding 100 feet, people can protect their homes and communities—“without necessarily controlling wildfires or altering vegetation,” Dr. Cohen notes. It is the characteristics and condition of the home itself and the vegetation within about 100 feet of it that mainly determine whether a structure will ignite. Beyond 100 feet, the condition of the vegetation “has nothing to do with the ignitability or likelihood a home will burn,” as Jim Furnish, former Deputy Chief of the US Forest Service, corroborates.

What most people don’t realize is that home ignitions are rarely caused by a wall of flame surrounding the home or moving through the community. Most often they are started by embers. In fact, 90 percent of ignitions start when embers land on a roof or in a pile of pine needles collected in a gutter, or when embers sneak into an attic vent and ignite the home from the inside. Wind-driven fires can blow embers up to two miles ahead of a flame front.

The key to avoiding home loss is to protect against embers. The most important defenses are:3

The Montecito Fire Department replaced this vent opening with a metal mesh screen at no cost. Source: Montecito Fire Department

Manage vegetation according to its zone. Source: National Fire Protection Association.

- Fire-resistant roof materials, typically asphalt or metal, maintained to be clear of small debris;

- Fine mesh screens that cover vent openings;

- Clean gutters or no gutters;

- Caulk or weather-stripping for gaps between roof covering and sheathing, around exposed rafters, and around garage doors and siding;

- Multipaned tempered glass windows;

- Noncombustible siding and deck materials, or proper spacing of deck boards and cleanliness below the deck and surrounding area;

- Within a five-foot perimeter around the house (Zone 0): Hardscaping with no bark mulch or other combustible material;

- Within 30 feet of the house (Zone 1): Pruning, removing, and/or spacing apart shrubs and trees; keeping grasses mowed; and removing mature canopies within 10 feet of the structure; and

- Within 100 feet of the house (Zone 2): Managing vegetation not to eliminate fire but to interrupt its path and keep flames smaller and on the ground.

The most devastating fires have resulted from a “domino effect,” where homes themselves are the primary fuel feeding a fire’s spread. This is why everyone needs to get on board with fire hardening. As we saw in Talent, Oregon; Santa Rosa, California; and Boulder, Colorado, communities are vulnerable even in areas that are not considered to be in the WUI.

Completing the fire hardening to-do list doesn’t have to be expensive. In fact, 79 percent of US homes already have a fire-resistant asphalt roof, and many have fire-resistant siding and other fire-resistant parts as well. Some of the most effective fire precautions require no more than a ladder, a $200 trip to the hardware store, some elbow grease, and regular maintenance (for example, installing fine metal screens over kitchen, bathroom, roof, and crawl space vents).

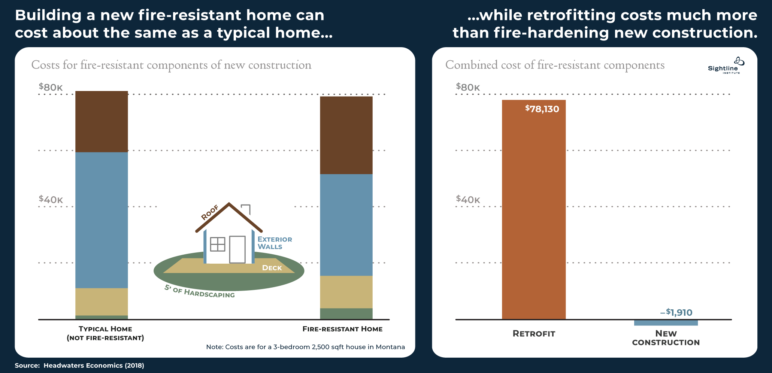

However, replacing all vulnerable components could add up. That makes it smart to fire harden new construction whenever possible. Regardless of whether a new home is to be fire-resistant, builders need to buy and install roofing, siding, and other materials. The cost difference between fire-resistant materials and typical materials is often minimal; in fact, sometimes fire-resistant materials even cost less.

Headwaters Economics found that a three-bedroom, single-story, 2,500-square-foot home in southwest Montana built in 2018 to meet the International WUI Code (IWUIC) cost 2 percent less than a typical (not fire-resistant) home. Retrofitting a conventional, non-fire-resistant home of the same dimensions to meet IWUIC—by replacing relevant parts of the typical house, like a cedar roof, cedar siding, wood decking, and a highly flammable juniper hedge—would cost $78,130. This adds urgency to states’ efforts to adopt wildfire building codes for new construction, if (as is likely) housing growth continues in the WUI.

These numbers are illustrated in the graphs below. (Note that plumbing, electrical, and other components that are the same for typical construction versus fire-resistant construction are not included.)

This doesn’t mean that retrofitting isn’t worth it. Even at a high cost of $72,000, retrofitting homes in high-risk areas yields about $2 in benefits (avoided costs) for every $1 invested. For a lower but still reasonable cost of $16,000, retrofitting returns $8 for every $1 invested. (But, as I’ll discuss below, the insurance company—not the homeowner—reaps these gains.)

These cost-benefit analyses only account for homeowners’ private benefits, which make up a fraction of the full costs of a fire. When the public costs (such as post-fire clean-up of hazardous materials) are factored in, the benefits catch up even faster to the costs of retrofitting, not to mention the increased safety for neighboring homes.

MARKET FAILURE CREATES DISINCENTIVES FOR HOME-HARDENING

Unfortunately, fire-adapted communities are not springing up on their own.

Unfortunately, fire-adapted communities are not springing up on their own. Homeowners do less home-hardening than benefit-cost analyses suggest they should, even when only their private costs and benefits are considered.

Embers on a roof can burn a house to the ground while leaving surrounding trees unharmed. Source: John Gibbins/U-T San Diego/ZUMA Press.

Public fire protection creates a substantial disincentive to building fire-resistant homes and to fire hardening existing homes. Research suggests that low rates of home hardening are likely driven by this market failure as opposed to a lack of cost-effectiveness.

Large public expenditures on wildfire protection erase much of a homeowner’s potential damage. Although enough fires escape to make fire hardening well worth it, 97 percent of fires are successfully contained. Homeowners do not pay anywhere near the full costs of fire protection, clean-up, or rebuilding, even where they do pay taxes or fees for fire protection. The value of this subsidy can exceed 20 percent of a home’s value in the western United States. As you move into progressively more extreme fire-risk territory, the per-house cost of firefighting soars, but homeowners don’t feel it.

This creates a catch-22: Unless communities in the WUI choose to invest in fire hardening, overwhelming political pressures will ensure that the public continues its immense wildland fire-suppression expenditures. As long as residents believe they’ll be protected, communities will not choose to invest their own money in fire hardening, and developers will not change how they build homes. And they’ll keep building homes in places “that are naturally black about every 20 years,” as William Bagley, emergency manager for the Klamath Tribes, puts it, “meaning that fire to some extent comes through and cleans things up.”

The most effective resolution is off the table because it’s politically impossible: the tough-love approach of entirely removing publicly funded fire protection and post-fire aid. (But, as I will describe in a future article, the tough-love approach could be implemented, and in the case of developing high-risk housing in the first place, it already is.) Several more practical policies could realign market signals to support fire hardening.

Five policies to help homeowners fire harden

Creating fire-adapted communities is one of the three pillars of the US Cohesive Wildfire Strategy. Moreover, success with the other two pillars—restoring and maintaining landscapes and wildfire response—depends on fire hardened homes.

Five complementary policies can help spread community fire hardening and make it a new norm.

Policy 1: require insurance discounts for hardened homes

If high-risk homes could recoup their fire-hardening investments through reduced insurance payments, they would have a real financial incentive to invest in fire hardening. Insurance companies usually evaluate fire risk based only on coarse measures such as zip code. Even when insurance companies do know the property-level risk based on statistical modeling, they usually ignore property-specific fire hardening. State Farm agent Truett Forrest of Pagosa Springs, Colorado, confirms this. “It doesn’t matter if they cut every tree and bush on their property,” he said. “We would not insure it because of where it sits.”

New policy in California would require insurance premiums to reflect both property-level home hardening and community-level precautions such as fire breaks. Once the kinks are worked out and insurance companies adapt to the new rule, other Cascadian states will have every reason to pass similar laws.

Policy 2: require home sellers to disclose fire risk

On top of market disincentives, people are notoriously bad at intuiting risk when the probabilities are low and the costs are high. Risk of home loss is escalating, but people’s perceptions of risk have not caught up, and we tend to exhibit risk amnesia or risk myopia. Right after a nearby fire, property owners are highly aware of risk and motivated to act. But within just one or two years, risk perception drops. (The Onion provides some comic relief on that point.)

Realtor.com listings

show how wildfire risk is predicted to grow and accumulate over 30 years. Cellphone screenshot by the author.

To encourage developers to voluntarily choose sites and materials that minimize fire risk, policymakers can require home sellers to give homebuyers accurate, future-oriented, and unavoidably conspicuous information on a property’s fire risk. If every listing showed fire risk alongside square footage and number of bathrooms, and if homeowners could improve their rating by fire hardening, it would also nudge homeowners considering whether to fire harden their existing homes. The listings on Realtor.com illustrate one way to do this. These listings provide not only an estimate of current risk but of future risk as well, and their calculations consider a property’s building materials and defensible space. Most states don’t require fire risk disclosures, and in those that do, the warning can be written in fine print on one among scores of pages of sales documents that a buyer doesn’t see until after they become emotionally invested. California already had such a law and passed a new bill last year to increase the saliency of the disclosures and the compliance rate.

Policy 3: Adopt and enforce mandatory wildfire building codes

Given the unfortunate market disincentives, the route to widespread fire hardening probably means mandatory building standards. Building codes are not new. It was new building codes that prevented widespread structural damage when Hurricane Ian pummeled Punta Gorda, Florida, earlier this year. The United States has nationwide building codes for homes in flood-prone areas. And California has had comprehensive wildfire building codes since 2008.

Recent research found that California’s fire-related building codes nearly halve the risk of loss should a structure be exposed to fire.4 Plus, protections on one home extend to neighboring homes, slashing their chances of burning during a wildfire. Dollar for dollar, the benefits of building to code unambiguously outweigh the costs in the most fire-prone areas. In places with only moderate wildfire risk, the gains of code start to wane on an individual level. However, accounting for future increases in fire risk and the public firefighting and clean-up expenditures that fire-vulnerable homes create restores the value of fire hardening investments once again.5

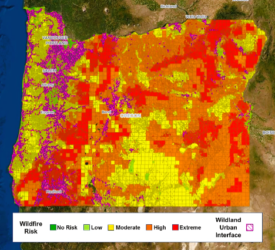

First draft of Oregon’s forthcoming wildfire risk map. Source: OR Dept of Forestry

Admittedly, adopting new fire codes for the WUI is politically challenging, which is why most states don’t require building with fire-resistant materials, even when rebuilding after a fire in a fire-prone area. With the passage of Senate Bill 762 in 2021, though, Oregon will become the second state with mandatory defensible space and home-hardening codes. SB762’s three main parts are:

- By October 1, 2024, maps will identify properties that both fall inside the WUI and are at high or extreme wildfire risk.

- New and existing structures on these properties will need to comply with new defensible space codes.

- New construction on these properties and replacement of a code-covered exterior component (such as a roof or siding) on an existing structure will need to comply with new wildfire amendments to Oregon’s Residential Specialty Code.

In Oregon, critics see the new WUI codes as “rural areas being lambasted with ridiculous requirements from Salem. Just another part of the urban-rural divide.” Some see the WUI codes as a “taking” that violates the Fifth Amendment of the US Constitution. But it’s not. It’s legally justified, like all building codes, by the immense savings in public firefighting expenses and the gains to public health and safety. Other WUI residents believe the myth that the forthcoming wildfire-risk maps will cause their insurer to cancel their coverage and, consequently, make their home impossible to sell. Rest assured, when insurance companies cancel a policy, it’s based on their own risk maps.

This is not to say that malaise about new regulations is unwarranted. Even among Oregonians who understand the importance of fire-adapted communities and support the new codes, few want to be told what siding to use or that they must remove the beloved larch that Grandma planted outside their bedroom window.

Policy 4: use public funding to boost fire hardening

Emergency donations for Lytton fire victims, at Shxwhá:y Village, Chilliwack, British Columbia. Credit: Amy Romer, used with permission.

Another reason that homeowners do not fire harden is that they don’t know how or can’t afford to. To help us all learn the somewhat confusing and sometimes disconcerting ins and outs of fire hardening, federal and state dollars could provide communities with independent experts (not from companies who stand to gain from recommended alterations) who can advise on what steps to take.

Some homeowners who want to fire harden simply can’t. Although there are plenty of second homes in fire-adapted landscapes, in US counties with the highest wildfire hazard, millions of people live in poverty, are elderly, have a disability, face a language barrier, or don’t own a car. Families without financial means cannot afford to reroof or replace their siding. Just removing one tree can cost more than $1,000.

State and federal grants and tax breaks could help cover the costs of home-hardening retrofits and maintaining defensible space for those with limited means. One example is California’s Home Hardening Program, which is currently operating as a pilot project in three counties. Homes receive up to $40,000 each for retrofitting with fire-resistant materials and creating defensible space. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) pays 90 percent of the cost. In response to growing evidence of unequal vulnerability to wildfire, the program laudably pays upfront instead of reimbursing homeowners. It also targets residents who have a disability, are over 65 or under 5 years of age, face language barriers, or do not own a car.

Direct service provision is another tool to popularize fire hardening. Ashland, Oregon, is training and paying professionals to create defensible space around 1,100 homes and to replace 23 wood shake roofs, paid for with a $3 million FEMA grant and $1 million from the City. In 2021, Oregon’s legislature authorized $200 million for programs that help homeowners create defensible space. According to its beneficiaries, the program has been a big success.

Jojo Jensen, who lives outside Eugene, received help clearing dry trees and other fuels from a ravine behind her house. Jensen and her neighbors paid to take down a 70-foot tree, and then workers from the nonprofit Northwest Youth Corps limbed it, cut it into smaller pieces, stacked what was good for firewood, and chipped the rest. Jensen also discovered an unexpected benefit. “The amazing thing is the community building in a time where neighbors don’t necessarily talk or even know each other,” she said. “Afterwards we did a weekend of work together as a neighborhood, and now our cul-de-sac is basically a tool lending library.”

A homeowner gets a fuels accumulation assessment. Source: Eugene Water & Electric Board.

But what Jensen didn’t get was any help with home hardening. The state program didn’t even mention it. In fact, despite what we know about the danger of embers and evidence that home hardening is more important than defensible space, Oregon’s program only assists with defensible space. And it’s not alone. Through the entire process of helping my mother make her home fire-safe, the Montana DNRC did not mention home hardening once. For public dollars to do the most good, programs can prioritize home hardening, as does the Retrofit Grant Program in Leavenworth, Washington.

Federal support to fire harden communities doesn’t come close to what is needed. And even though fire hardening is more effective in general, federal and state spending overwhelmingly goes to fire suppression and, to a lesser degree, thinning and prescribed burns.

Policy 5: Most important, redefine the problem

Finally, from the media to federal policies, we share a collective misunderstanding about how to prevent damage to homes and communities. Dr. Jack Cohen believes that this is the fundamental obstacle to a more rational approach to wildfire. He wrote in an email, “Until an appropriate problem definition occurs, leading to a completely different approach, policy is . . . a hindrance to progress.”

To shift ingrained beliefs, the media can help in several ways: by describing fire in neutral terms instead of alarming and negative ones; by measuring the amount of damage in terms of community destruction rather than acres burned; and continually reminding us that fires are natural and, more often than not, restorative.

The federal government can help by shifting funding from fire suppression to fire hardening. Aside from directly advancing fire-adapted communities as described earlier, this would cue a shift in our collective understanding of what causes wildfire damage and what can prevent it.

These changes won’t be easy. Agency personnel and historians argue that since its inception and through the present, the US Forest Service has had to sacrifice some aspects of science-based management in exchange for an operating budget. Gifford Pinchot, the very first chief of the US Forest Service, understood the ecological importance of fire but promised to eliminate it because that was the only way to prevent critics in Congress from terminating the Forest Service and liquidating the public forests it oversaw.

And politicians today still court fire-suppression votes. Even though a late and wet spring was a much more important factor, Washington Commissioner of Public Lands Hilary Franz said that the mild 2022 fire season was not due to chance but rather to the new Kodiak airplanes, new bulldozers, and additional firefighters that arrived under her watch.

Preparing for a fiery future

The old paradigm of dealing with wildland fires by suppressing them can no longer protect homes; it never worked to nurture healthy forests; and we can’t afford it anyway.

If we want to reign in runaway wildfire suppression costs and mounting community damages, Cascadia needs a new approach to living with wildfires. The old paradigm of dealing with wildland fires by suppressing them can no longer protect homes; it never worked to nurture healthy forests; and we can’t afford it anyway. The media, federal budget writers, state legislatures, and communities can all help create vital new norms as we learn to live with the new wildfire normal and as we continuously develop resilience as our climate changes.

Jodie Hettrick, former fire chief for Anchorage, Alaska, is optimistic. “I hope that in the future we become better stewards of the use of fire and more responsible about protecting our own homes and properties,” she said. “I think people are getting much more cognizant of that.”

Residents of Detroit, Oregon, gather together after the Santiam Fire burned over 1,500 homes. Source: InciWeb.