It’s time to address the elephant in the room: the best and possibly only practical way to protect homes from fire is to stop building so many of them in places that are primed to burn. According to Dr. Jon Keeley, a fire ecologist with the United States Geological Survey, “People are so fixated on climate change, which is a very real concern, but the bigger driver of accelerating wildfire damage is building houses in the WUI.” The wildland-urban interface (WUI) is the area where houses are built in or near natural areas—either through urban sprawl or when satellite developments or individual houses spring up in the midst of forest, shrublands, or grasslands.

This concern is urgent. Wildfires are bigger than ever. Many are impossible to fight. Yet people are flocking towards fire-prone lands and populating the wildland-urban interface faster than any other area in the United States. Some developers are building new homes in the very footprint of recent wildfires. It’s worth emphasizing the obvious: without costly firefighting, these homes will burn down.

These houses trap us on a wildfire treadmill by impeding efforts to restore wildlands to health through “beneficial fire.” They also ensure the diversion of billions of tax dollars to an expanding arsenal of bulldozers, aircraft, and firefighters.

We can’t stop population growth. Cascadia is and will likely remain a major receiving zone for people who appreciate its natural wonders and for climate migrants. What we can do is guide this growth away from fire danger.

According to Tim Trohimovich, Director of Planning and Law at the growth management advocacy nonprofit Futurewise: “There’s no doubt that the cities and towns and their environs where it makes sense to grow are big enough to accommodate all of the population increase in Washington, Oregon, Montana, and Idaho. We don’t need to build on forestland, grasslands, or farmland.”

In a true meritocracy, the 2023 firefighter of the year award would go to city infill because new construction within existing urban areas is the most effective way to lower our collective fire risk. Runner-up would be compact development contiguous with existing city limits. If past fires are any indication, compactness is the single most important protection against wildfire damage.

Fire-hardening communities against inevitable wildfire is important, but preventing development in fire hazard zones is how we solve the wildfire crisis.

Flocking to fireplains ignites fires and firefighting costs

Between 1990 and 2010, the number of new houses in or near wildlands in the United States grew by 41 percent. Even more surprising, the number of new homes where fires have recently burned grew by over 60 percent.

Just as it has maps of floodplains, the United States maintains maps of wildfire hazard that chart where fires frequently burn. You can think of these areas as “fireplains.” But unlike floodplains, construction in fireplains is not regulated. And fireplains are expanding as the atmosphere warms.

People are moving into fiery rural places primarily for the amenities. This has become possible with improvements in the communication infrastructure, expansion of the service economy, and the ability to work from home. And, of course, free wildland fire suppression. About 15 percent of WUI houses in the West are second homes. Of course, plenty of people are moving to the WUI to afford a home.

WUI growth tends to follow the riskiest patterns: dispersed, detached housing and isolated clusters of houses surrounded by open space. Planners call the latter “leapfrog development” because developers hop over land close to a city or town and instead erect structures farther away, leaving forest, grassland, or shrubland between clusters of buildings.

Constructing residences near forests and other wildlands in fireplains poses four main problems.

- More homes—and the people they house—tremendously increase the risk and occurrence of wildfires to begin with. Oregon’s Eagle Creek Fire that ultimately burned 48,000 acres in the Columbia Gorge was started by teens throwing fireworks. California’s Ranch Fire, spreading over 410,000 acres, was sparked by a hammer driving a metal stake. Whether it’s burning debris piles, discarded cigarettes, arson, or downed power lines, people start 84 percent of wildfires and 97 percent of those that threaten dwellings.

- There are more lives and homes at stake. More than any other variable, including the hotter and drier weather of climate change, the location of housing growth has had the greatest impact on how many human and animal lives and residences are lost to fire.

- WUI growth in fireplains is the single greatest factor driving skyrocketing suppression costs. The United States’ annual firefighting bill grew twentyfold over the past 35 years, hitting $4.5 billion in 2021. Not only does WUI growth cause more fires but suppression costs ten times more when a house is at risk.

- Building houses in fireplains keeps us trapped on the wildfire treadmill. When dwellings are near wildlands, it becomes hard or impossible to get more “beneficial fire” back onto landscapes.

Trapped on the wildfire treadmill

As I wrote recently, we are trapped on a wildfire treadmill: the more we suppress fires, the worse they get; and the worse fires get, the more we suppress them.

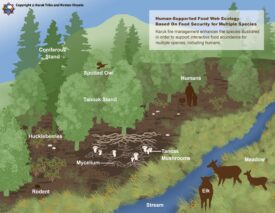

To get off the wildfire treadmill, we need to restore forests and clear out forest fuels by returning low- and moderate-intensity fires to the land. Forest and other land managers have three main tools to do this: 1) managing wildfires to maximize the amount of beneficial fire during both suppression operations and when conditions are safe for “managed wildfire for resource benefit”; 2) intentionally starting controlled fires, called prescribed burn; and 3) when used in combination with fire, mechanical treatments (i.e., thinning) to reduce tree density and other fuels.

An expanding WUI (i.e., more sprawl) narrows our chances of success.

In the United States, about 100 million acres of seasonally dry federal lands are at high risk of wildfire.1 Much of this area needs fire to return about every 20 years. This requires tremendous resources—personnel, equipment, and bandwidth—resources that are getting tied up fighting the growing number of increasingly expensive fires near new WUI developments.

Building near wildlands also limits our ability to use fire as a tool. Even small managed fires carry risk, and supervisors are less willing to burn near residences because of the liability should anything go wrong. Fires create smoke and, although unusual, managed and prescribed fires can grow out of control. When houses are nearby, the potential for them to cause damage surges.

For these reasons, forest managers can’t use “managed wildfire for resource benefit” anywhere near communities.

Even prescribed fire is impeded by houses. Burn bosses can only green-light a controlled burn near a community if the calculated risk that the fire will escape falls below a threshold based on computer modeling using wind, temperature, humidity, and the forecast for rain.

Another bar to clear is air quality. Kara Karbowski, who coordinates prescribed burn programs in Washington, told Sightline, “We don’t want to smoke out communities, right? On those days where it’s going to impact the community, no one’s burning.” In her experience, “If you go to certain parts of the state, where there’s less people, there’s less opportunity for that.”

Ultimately, the objective is to let as much low- and moderate-intensity fire burn as we safely can. This will save lives, lessen smoke, reduce carbon emissions, and make forests healthier. Building houses in the wildland-urban interface blocks this exit from the wildfire treadmill.

Three tools to redirect growth

By 2040, Idaho is predicted to house an additional 660,000 people. Washington state will likely house an additional 3 million. Without planning and policy, millions of new structures will go up in Cascadia’s WUI fireplains.

When a new house goes up in a fireplain, it perpetuates the wildfire treadmill, raises taxes and insurance premiums across the country, and exposes people near and far to dangerous particulate pollution. The new homeowners don’t pay these costs.

If Cascadians want to guide population growth to safer places where it doesn’t burden the public, they can do so in three main ways, none of which would be politically popular. But the urgency of the growing costs of wildfires—in lives, homes, and forest health—demands that people think differently about the communities they’re building, making some concessions up front to avoid likely greater losses down the line.

1. Channel growth toward towns and cities

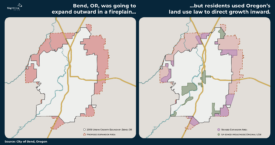

Where enacted, land use and growth management laws have silently prevented wildfire damage for decades by guiding population growth into cities, containing sprawl, and keeping open spaces open. These protections are not designed to stop growth but to optimize how growth happens. They result in more concentrated and efficient use of land, coordinated infrastructure and public services, and protected natural resources.

According to Joshua Chandler, city planner for The Dalles, Oregon, “by establishing urban growth boundaries, Oregon has avoided what continues to happen in California with sprawl.” If California had similar growth laws, wildfire damage would be a fraction of what it is today.

All Cascadian states can make their communities safer by improving land use policy to keep homes out of wildfire harm’s way, even Oregon. Under its land use law, counties must identify natural hazards, but they don’t have to protect against them. According to Rory Isbell, staff attorney at Central Oregon LandWatch, “You could strengthen [the law] to say no new development or no conversion of farm or forestland for residential uses in your areas of high or extreme fire risk.”

2. Eliminate perverse incentives

By fighting forest fires, by purchasing mortgages in the wildland-urban interface (through Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac), and by installing broadband and other infrastructure regardless of the area’s fire risk, the US federal government encourages growth in the fire-prone WUI.

If it wants to lower its own wildfire bill and protect public health, it needs to eliminate these and other perverse incentives and stop subsidizing building in fireplains. This includes forgoing the creation of a federal wildfire insurance program and avoiding repeating the mistake inherent in the National Flood Insurance Program, which has caused population to increase in high flood-risk counties.

Local and state governments also face a moral hazard. They benefit from the tax revenues and economic growth that development brings, but when wildfire strikes, the federal government typically foots most of the recovery bill. The federal government can’t tell people where they can and cannot live, but it can put pressure on state and local officials by conditioning federal grants on their adoption of wildfire-mitigating growth policies.

3. Stop shielding new houses from the full costs of risky areas

Many people yearn to live in a forested landscape. Free firefighting services and subsidized insurance allow them to do so. Between 2010 and 2020, people generally moved away from areas with frequent hurricanes and heat waves, disasters that cannot be “fought.” But they moved into areas with higher risks of wildfires.

Even without a nearby fire, a new dwelling in the fireplain already costs taxpayers. For 2023, the US Forest Service budgeted $1.3 billion dollars for “wildfire preparedness.” This includes research and development of firefighting technology; educating communities; training, transporting, feeding, and housing firefighters; purchasing, operating, and maintaining aircraft and bulldozers; and contracting for private fire aviation companies to remain on standby. For fires that require heavy firefighting, suppression spending adds another $1 billion to the budget.

Houses in fireplains also increase the insurance rates of policyholders everywhere. After the 2021 fire season, home insurance premiums soared, with policyholders in safe areas picking up much of the tab. Some 90 percent of US homeowners swallowed an unusually steep jump, with premiums in Washington state, for example, up by 18 percent.

Think like it’s already 2070

Max Moritz, a UC Cooperative Extension Wildfire Specialist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, has a warning for Cascadia: “I live in Santa Barbara, where it’s always hot and dry, and it’s fire-prone much of the time. But when the Pacific Northwest, with all that biomass, starts getting the same periodic warm droughts and wind events, it’s gonna be a spooky place to live.”

It’s hard to imagine what we have not experienced. But if Cascadians can start designing forward-looking communities to thrive in an increasingly fiery future, we can save lives, avert enormous financial consequences, and step off the wildfire treadmill.

After years studying wildfire in the West, Dr. Jon Keeley, fire scientist for the US Geological Survey, believes that “ultimately, what will solve the wildfire problem is not firefighters but concerned politicians who find a way to pass ordinances and laws to manage growth.”

Alec

How does WUI fire risk compare to the fire risk of denser urban areas? I’ve heard people write condo fires are so rare they’re newsworthy, while WUI fires happen all the time, but maybe some evidence would help? When another fire starts in an urban area, what’s the risk there? How are the risks assesed when comparing these two different environments? Fire risks are already used as a card to stack against any denser occupancy, like a mobile home in a backyard, sharing a bathroom in the larger structure. They’re also probably used as a card to stack on a smelly compost. Furthermore, it’s extremely frustrating when delivery personnel literally have no way to get out of a building, if they take the stairs down, besides pounding on the locked door of a first floor lobby, defeating the whole point of stairs. I can’t say stair placement mandates are just an excuse to make denser areas prohibitively expensive, but I have to wonder.

Nancy Padberg

I live on 2+ acres in Zigzag, Oregon up on Mt. Hood. We have AntFarm, a not for profit organization in Sandy, that helps so much. I signed up for the Fire Prevention program and they came here for 2 days and removed lower branches of trees, shrubs, made space between trees, etc. FOR FREE!! Almost all of the 12 neighbors on our 1/2 mile road got their property done the next year. My goal is to keep maintaining fire prevention. I live in HEAVEN and don’t want it to burn. And am ready for when the earthquakes and tsunami’s hit the coast and many come up to the mountain. Our fire department has even had meetings about this issue. How about if we ban fireworks. Those were likely a kid from town that started the Columbia Gorge fire. And then there is lightning. That started the fires near Bull Run. And MAYBE wise management of forests. I can’t live in town. I moved here 26 yrs ago and will stay here until I die.