UPDATE 03/15/23: SB 5723 did not advance out of the Senate Rules Committee by the deadline. During the process, a modified version of the bill that excluded municipal court judges was approved by the Senate Committee on State Government & Elections.

Oregon and Washington have long been leaders in modernizing democracy. Both automatically register people to vote when they get a state ID, for example, and both states make voting easier by mailing ballots to every voter. In national elections, they are turnout champions: in 2020, they tied for third place among all states. Some 76 percent of eligible adults in each state cast valid ballots in the November general election that made Joe Biden president.

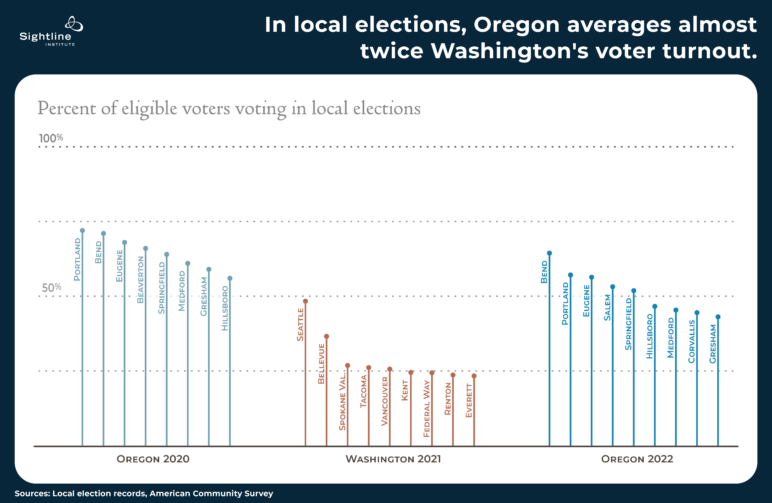

In one category, though, Washington trails Oregon by a mile: turnout in elections for municipal offices such as mayor and city council. In local elections, Oregon’s turnout is almost double Washington’s.

The reason has nothing to do with virtue or civic-mindedness, with voter suppression or get-out-the-vote campaigns. It’s the two states’ schedules. Oregon holds city elections at the same time as state and federal ones, in November of even years, on the election day that rules them all. In Oregon as in many states, there are a few other election days, but the state holds local elections on the day that voters think of as the real deal, as Election Day.

Washington holds city elections in November, too, but always in odd years, out of sync with state and federal races and at a time when attention is elsewhere. In fact, Washington bars cities from running elections on capital-E, capital-D Election Day. Cities do not have the right to choose when to hold their elections.

A bill in the Washington legislature, Senate Bill 5723, would lift that ban—an important measure with numerous benefits, including:

- Boosting local turnout far more than any other reform available;

- Improving local representation dramatically, so that the local electorate and elected officials better reflects the demographics and beliefs of the population; and

- Improving accountability by better aligning local government decisions with local public opinion.

(Consolidating local elections also usually saves public money and dilutes the influence of special interests, as I’ll document in a subsequent article.)

Consolidated elections turbocharge local turnout

When Austin and Phoenix switched elections to Election Day, local turnout rose 2.5-fold. When Baltimore did so, it was 3.5-fold, and El Paso 4.5-fold. Turnout in Los Angeles city council races rose more than 3-fold. Among 54 other California cities that switched to even-year November elections in 2016, 2018, and 2020, average local turnout tripled. Professor Zoltan L. Hajnal of the University of California, San Diego, writes:

Every one of the eight published studies on local election timing finds that moving to even year elections (often called on-cycle elections) is by far the biggest thing that localities can do to increase turnout. Nationwide, local voter turnout generally doubles when elections move from off-cycle to on-cycle contests.

That’s a remarkable finding, considering that get-out-the-vote and registration drives are lucky to boost participation just by a percentage point or two. In fact, the turnout dividend of on-cycle local elections outstrips those of all other much-discussed voting-system improvements, such as automatic voter registration, election-day registration, a 15-day early voting period, universal vote by mail, and the prohibition of voter ID laws. Indeed, on-cycle elections raise local turnout more than all of these voting upgrades combined, according to the best academic analyses. (Not that officials have to choose, of course. They can implement all these reforms.)

If Washington were to let cities move their elections on cycle, those cities could reap impressive increases in turnout, too. What’s possible is vividly apparent in the contrast between Washington and Oregon, Washington’s southern neighbor and closest analog among the states. Since 1917, Oregon state law has required that all local elections take place in November of even years. Oregon has one big Election Day, where voters mark their ballots on everything from US president to town council. Consequently, almost as many Oregonians vote in local races as in presidential or gubernatorial races.

Sightline gathered data from the largest cities in Oregon and Washington, finding in each municipality the citywide race with the most votes cast in recent municipal elections. For example, in Oregon, the 2020 Portland race for mayor was a closely watched and high-stakes competition. In it, 72 percent of the adult citizens of the city cast their votes. That was Oregon’s high-water mark of turnout that year for a city election, and the low-water mark was 56 percent in Hillsboro. The average was 65 percent. Two years later, in 2022, there was no presidential election to motivate participation, and turnout in Oregon cities fell by more than 10 points. The high-water mark was 64 percent in Bend, and the low-water mark was 43 percent in Gresham, with an average of 51 percent.

Still, even the lower 2022 local turnout in Oregon towered over participation in Washington cities in their 2021 odd-year elections. Washington averaged local turnout of just 29 percent—that’s 22 points less than Oregon cities’ 2022 average and less than half of their 2020 average. Washington’s turnout leader was Seattle, where the mayor’s race drew 48 percent of eligible voters to cast a ballot; the laggard was Everett, where just 23 percent did.

Some critics of on-cycle elections worry that voters will tire when presented with a long ballot and quit before getting to the bottom. Down-ballot “drop-off” or “roll-off” happens in almost all elections, but its scale is minor—a few percentage points—compared with the boost on-cycle elections bring. In Sightline’s comparison, moreover, drop-off is irrelevant: Sightline only tallied ballots marked for local races, and even after any down-ballot roll-off, Oregon cities in our combined 2020 and 2022 samples still had 93 percent more turnout, as a share of eligible voters, than their Washington counterparts in 2021.

Some critics of on-cycle elections worry that voters will tire when presented with a long ballot and quit before getting to the bottom. Down-ballot “drop-off” or “roll-off” happens in almost all elections, but its scale is minor—a few percentage points—compared with the boost on-cycle elections bring. In Sightline’s comparison, moreover, drop-off is irrelevant: Sightline only tallied ballots marked for local races, and even after any down-ballot roll-off, Oregon cities in our combined 2020 and 2022 samples still had 93 percent more turnout, as a share of eligible voters, than their Washington counterparts in 2021.

Consolidated elections mean winners who better reflect voters and their views

A larger electorate is also a more representative electorate; it’s one that better matches the public in its race, ethnicity, values, and—especially and above all—age. Vladimir Kogan of Ohio State University and his coauthors found that in California and Texas, for example, voters aged 65 years or more made up 37 and 39 percent respectively of the presidential-year electorate; their share rose to well over half in off-cycle elections. Among 50 US cities studied by Portland State University, off-cycle elections for mayor brought out mostly old voters; a 17-year gap separated the median age of voters from that of the public in their cities. In cities with on-cycle elections, in contrast, this age gap shrank by half.

Similarly, in Seattle, those who vote in even-year Novembers include a more representative share of young voters and voters of color, while Seattle’s odd-year electorate is much older and whiter than the population. The same pattern is evident across Washington: in odd-year elections since 2000, voters under the age of 25 made up just one-quarter their share of the voting-age population. In even-year elections, though, their turnout rate almost tripled. Washingtonians under 25 are just one-fourth as likely as seniors to cast ballots in off-cycle elections but are more than half as likely to vote on cycle.

The pattern holds across the United States, too. According to UC San Diego’s Professor Hajnal, “[O]lder voters (those aged 65 or older) tend to dominate odd-year contests. In odd-year elections around the country, working-class Americans, racial and ethnic minorities, and other disadvantaged groups are . . . underrepresented.” Writing elsewhere with Dr. Kogan of Ohio State and Agustin Markarian, also of UC San Diego, Hajnal notes, “Whites . . . are almost twice as likely as Latinos and Asian Americans to participate in local contests. The imbalance by education, income, and age is just as stark.”

On-cycle elections, in contrast, bring out an electorate that looks like the public, and those high-turnout electorates choose candidates who look like them as well: localities with high-turnout elections elect far more city councilors of color than do localities with low-turnout elections, for example.

On-cycle elections also favor candidates whose values match public opinion more closely. Researchers Michael Hartney and Sam Hayes compared school board members’ views with their constituents’ and found that school boards elected in even years match public sentiments better than do boards elected in odd years.

How to achieve consolidated elections? Let cities choose them

Election consolidation might double local turnout, yielding a more representative electorate. But what is the political path to reform?

More than a century ago, from 1894 to 1917, the Progressive movement set about breaking American cities’ “political machines,” in which local bosses used patronage networks to generate huge turnout of local voters for state and national parties. The Progressives’ motives and record were mixed: they aimed to fight corruption, it’s true. But they did it partly by disenfranchising ethnic and working-class voters. Their first tactic and one of their most successful was to disconnect local elections from state and national ones, by shunting them to springtime or to odd years. This splitting of local from state elections stuck, and a large majority of US municipalities still hold their elections off cycle.

Oregon was a hotbed of Progressivism. Its “Oregon Plan” of allowing citizens’ initiatives, referenda, and recall petitions was famous at the time and won emulation from many other states. Perhaps because it had these tools so early, it went the opposite direction from other states on local election timing. In 1917, voters in Oregon did what voters have subsequently done in many cities: they voted overwhelmingly for a citizens’ initiative to consolidate local elections. Tired of city elections that were all over the calendar, they enshrined in Oregon law a provision that is the model of simplicity: “All elections for city officers shall be held at the same time and place as elections for state and county officers.”

In Washington, in contrast, city election timing has never been on the statewide ballot. In 1921, the state legislature channeled all city elections to the spring but let cities decide which years. Subsequent laws bounced election schedules around, this way and that, and began to sort them into odd years. Finally, in 1963, the legislature asserted control over all city elections, requiring that they take place in November of odd years. There they have remained ever since.

The vintage of Washington’s election calendar is no badge of pride; being a product of the 1963 legislature might even count as a stain. According to the legislature’s own official history, the session was dominated by bitter and acrimonious infighting. Then-Governor Al Rosellini (D) called it the worst do-nothing legislature in his 25 years of public service. It barely even succeeded in adopting a budget, any legislature’s most basic duty. Apparently, the only thing legislators could agree about in 1963 was to keep cities from running high-turnout local elections.

Oregon exemplifies what turnout could be like in Washington, but it is not a good model for how to move elections on cycle in the first place. A statewide initiative, as in Oregon in 1917, would probably pass in Washington, because voters almost always approve election consolidation. But getting such a measure on the ballot would be a daunting prospect, because few people get excited about the topic. It’d be hard to recruit volunteers and contributors for a campaign.

Better models are California and Nevada. They stopped barring cities from running on-cycle elections, and cities took advantage of their new options. As I detailed in a previous article, in 1981, California began allowing all cities to consolidate elections. One by one, cities considered their options, calculated potential cost savings and turnout increases, and a steady stream of them switched over. In 2003, Nevada gave the green light to consolidation, and cities responded in the same way. Soon, a majority of California and Nevada cities had consolidated local elections. Just so, in the roughly 20 states that let cities choose even-year Novembers for their elections, the consolidation trend is unmistakable. In 2022 alone, voters in 11 cities—from St. Petersburg, Florida, to Fort Collins, Colorado—approved the switch.

In Washington, reformers led by Rep. Mia Gregerson (D–SeaTac) previously attempted to pass a bill that required on-cycle local elections, but they never got far. Cities objected, not liking to be told what to do, and few legislators or citizens cared enough to push back.

This year, Washington State Senator Javier Valdez has developed a new bill. It’s a modest reform: it allows cities to decide whether to consolidate elections. That’s all. “This is an idea we believe can garner the votes needed in the legislature to be adopted into law sooner rather than later,” said Andrew Villeneuve, executive director of the Northwest Progressive Institute, which has been a leader in the movement for on-cycle elections in Washington. Passage would likely unleash the same stream of local election consolidations that California and Nevada experienced.

SB 5723 would lift the ban on cities scheduling their elections on the highest-turnout days of each biennium. It would let them decide for themselves, after considering costs, logistics, and benefits, whether to consolidate locally on the election day that rules them all, the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November of even years. It would let cities hold elections on Election Day.

Data in support of the figure and explanation of Sightline’s method are posted here. Thanks to Senior Research Associate Jay Lee for data analysis, to volunteer Todd Newman for legal research, and to former Sightline board chair David Yaden for Oregon historical research. I am grateful to Avi Green, Zoltan Hajnal, and Neal Ubriani for critiquing an earlier draft of this article.

RDPence

I’m concerned about ballot length when local elections get combined with national and state elections. Two sides to the ballot paper are already filled, and now we’re going to add county and city and school district and port district (etc. etc.) to the ballot?

Can they make the ballot paper long enough, or will they need to print and count two ballots for each voter?

Not to mention the voters’ bandwidth~ after deciding all the national and state choices, they have to continue through all the local races. I expect to see more voter fall-off towards the bottom of those bedsheets ballots. That and automatic voting for familiar names (incumbent protection act).