Takeaways

Portland’s mandatory affordability program seems to be fully funded in the Central City but underfunded elsewhere.

A fully funded program would efficiently create more market-rate homes and more below-market homes citywide.

Maximizing lower-income households in high-opportunity areas would play to the program’s strengths while eliminating unintended subsidies for market-rate homes.

Find audio versions of Sightline articles on any of your favorite podcast platforms, including Spotify, Google, and Apple.

In 2016, when Portland’s city council voted to start requiring a share of homes in new buildings to be made affordable to lower-income Portlanders, some predicted disaster.

“Could well make the city’s housing affordability problems demonstrably worse,” urban economist Joe Cortright warned.

Others rejoiced.

“Would harvest the windfall profits that our wildly inflated housing prices are creating,” John Mulvey, a housing advocate with the East Portland Action Plan, predicted.

Others said that it might need to be adjusted in the future.

“At the earliest possible stage, if there is a need for us to reconvene and rethink any part of it… I want to make sure that that’s baked into our policy,” City Commissioner Nick Fish said.

Well, it took six years for the city to get around to it, but that self-assessment is finally underway—and it points the way to a handful of relatively modest changes that could mend (and not end) a program that looks like a pretty good deal for both tenants and taxpayers.

Since last fall, I’ve been honored to serve among 10 fellow Portlanders on the city’s volunteer “inclusionary housing calibration work group” that has teamed with the city’s staff and consultants to dig into the program’s numbers, goals, outcomes, and future. Though there have been a few moments of healthy tension, the process left me impressed by the city staff’s interest in getting the details of this policy right.

In that time, I’ve also learned just how unusual Portland’s program is among similar “inclusionary zoning” programs. The key difference: unlike almost all similar programs in the United States but like more productive flavors of inclusionary zoning such as this one in France, Portland’s program is at least partially funded.

In Portland, the public pays for the program in the gentlest of ways: by waiving some taxes and fees on buildings that comply with it. And as the city’s contractor found, that waiver can potentially be enough to make the program work. The catch: if the program will both maximize the number of below-market homes and avoid driving up market prices, it needs full funding.

Happily, full funding is within reach. With just a few tweaks, criticism of Portland’s program would likely recede. In fact, it can become a model for other North American cities that want to mandate mixed-income homes in new buildings.

Here’s what that would take.

1. Define success

Portland’s program has an essentially qualitative purpose statement: the program should “increase” the number of less expensive homes available in areas with “superior access to quality schools, services, amenities and transportation,” especially affordable to households making less than 60 percent of the city’s median income. (For a one-person household, that’s $47,400; for a three-person household, it’s $60,960. At those incomes, federally defined “affordable” rents, including utilities, are capped at $1,185 for a studio, $1,524 for a two-bedroom, and so on.)

Having a purpose is good. But Portland hasn’t actually set any quantitative criteria for the city to judge this program’s success or failure. This is bad.

Here’s one simple figure that could be used to evaluate the success of the program: not just to “increase” but to maximize, given available public resources, the number of new homes in desirable areas that are affordable to Portlanders making 60 percent of the median income.

This is a crucial difference. Any construction at all under a mandatory inclusionary housing program will “increase” the number of below-market homes built, compared to a city with no such program. Someday, Portland might mandate that 40 percent of homes in new buildings have regulated affordability, with no public funding to offset those costs. If that set of rules resulted in a single 100-unit building each year, the current program language would count those 40 homes as a sign of success.

But in a city of 600,000, just 40 new below-market homes per year isn’t a success. It’s a flop. A “maximization” policy, by contrast, wouldn’t be satisfied with a flop. Instead, it would keep pushing Portland to fund its mandates. This is what’s needed to make them productive.

This principle can unite Portland’s left (which tends to advocate most fiercely for below-market homes) and center (which tends to advocate most fiercely for market-rate homes). A strong inclusionary housing policy is a win-win from both these perspectives.

2. Fully fund it

The crucial piece of a healthy inclusionary zoning policy is simple and intuitive: public benefits require public expenditure.

The good news is that this expenditure doesn’t need to be huge.

The city’s economic consultant found that although Portland’s inclusionary housing program is not currently fully funded, there’s a clear path to getting it there, at least for rental properties. But it will take a little time to explain why the program is working in one part of the city and not in another.

2a. Today’s program in central Portland: fully funded and cost-efficient

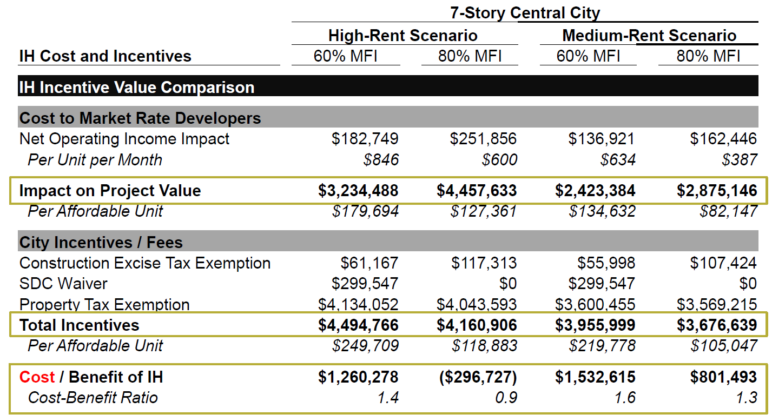

Below is a financial analysis of Portland’s program as it applies to the “Central City,” local planning jargon for both the skyscraper-studded downtown and the ring of neighborhoods around it on both sides of the Willamette River, west to Interstate 405 and east to approximately 12th Avenue.

The tables below summarize research by BAE Urban Economics, a consulting firm hired by the Portland Housing Bureau to interview local development industry professionals and capture current development cost factors. This first table imagines a hypothetical 7-story apartment building in central Portland. Four Central City scenarios for that building are listed: a “high-rent” location and a “medium-rent” location, and in each of them the city’s two primary ways for buildings to comply with inclusionary housing rules, the so-called 60% MFI option (in which buildings set aside 10% of their homes to rent at fairly low prices) and the so-called 80% MFI option (in which buildings set aside 20 percent of their homes to rent at more midrange prices).

Here are two important things to notice in this sea of numbers:

In these Central City scenarios, the program is healthily funded. Look at the bottom line, labeled “cost-benefit ratio.” This is the cost of the inclusionary housing program (to the public, in waived taxes and fees) divided by the benefit of the program (to the public, in the form of rents that are lower for some homes than they would otherwise have been).

For a program in perfect balance, the figure would be 1.

In each price scenario (“high-rent” and “medium-rent”), the developer of this hypothetical project has an option (60% AMI) where the tax and fee breaks (“city incentives/fees”) exceed the costs of offering some homes below market value (“cost to market rate developers”).

However, because the program also puts some administrative costs on landlords that aren’t captured above, it may make sense to target a ratio a bit above 1. Is 1.4 or 1.6 more tax abatement than necessary? That’s debatable. However, we might not want to worry about it because…

Even in the fully funded scenarios, the “incentives per affordable unit” line is below $250,000. This is the combined value of all the city’s tax and fee waivers divided by the number of below-market homes. As affordable homes go, this is quite a good deal. In Oregon, apartments in dedicated “affordable housing” projects currently require an average of about $225,000 from the state trust fund and federal tax credits, typically matched with locally administered federal and local funds. The city’s inclusionary housing program, by contrast, is doing the whole job with that sum in local funds alone.

Consider, too, that these affordable homes aren’t cutting corners by concentrating poverty in low-rent areas. The whole concept of inclusionary housing is that it ensures that some low-price homes end up in the sort of desirable areas where people are willing to pay relatively high market prices. If the public wants to make investments in affordable housing, this looks like a relatively efficient one.

2b. Today’s program outside central Portland: underfunded and malfunctioning

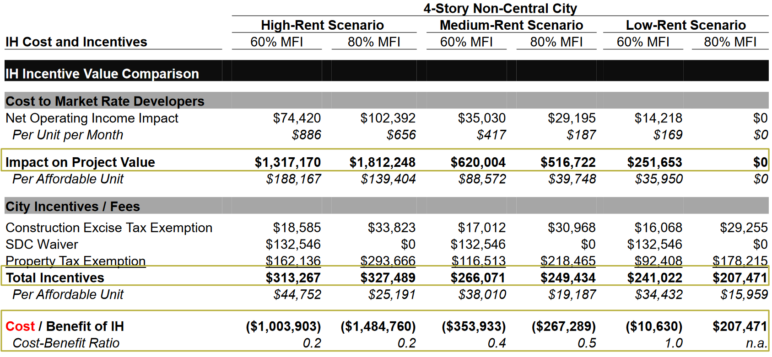

Outside of central Portland, by contrast, the city’s economic analyst found signs of trouble. Here’s the same table again, this time with “low rent” scenarios added:

Outside the Central City, the program is deeply underfunded. Check out the crucial “cost-benefit ratio” line this time. In the places outside the Central City where people most want to live (the places that can command the highest rents), the program is only about 20 percent funded today. For a hypothetical four-story, 84-unit apartment building, the project is short at least $1 million, which means that these 84 homes (nine to 19 of which would have been priced below market) won’t get built at all until market-rate rents in Portland climb by hundreds of dollars per month. That’s probably not the world Portland’s leaders want to create.

Even in medium-rent scenarios, the program is at most half funded. It’s not until you get to truly low-rent parts of Portland (mostly east of Interstate 205) that the program comes close to balance again, simply because there’s not much difference between the officially “affordable” rent and the market rent. But in low-rent areas, market rents generally aren’t high enough for anyone to be building new apartment buildings anyway.

When an affordability mandate is heavily underfunded, developers start bending over backwards to game it. Pages 12 to 15 of this city slideshow offer a tour of the ways that’s happened in the last several years: buildings that are slightly too small (19 units) to trigger the affordability mandate; big projects split into multiple 19-unit buildings; and buildings of nothing but studio apartments, to get a tax break on a housing type that’s already inexpensive.

A city analysis found that though these 12- to 19-unit buildings still aren’t common, the number of new homes in such buildings approximately doubled when the city’s affordability mandate was introduced in 2018, and that number has been more or less consistent since. That’s real-world evidence of an underfunded program that is a net cost burden on projects of every size.

Bringing the program into balance would require a larger property tax abatement. Why is the program fully funded in central Portland but not elsewhere? Because in central Portland, local taxing districts currently waive property taxes on the entire building for 10 years; outside the Central City, they waive those taxes only for the below-market units. There’s a simple fix here: the city and Multnomah County would need to agree to temporarily waive property taxes on a larger share of buildings outside the Central City as well.

The program would be fully funded just by waiving taxes that are not currently being collected on buildings that do not currently exist.

3. Smooth it out

As you may have gathered by now, one awkward thing about Portland’s inclusionary housing system is that it assumes there are exactly two parts of Portland: the Central City and everywhere else.

But that’s not how Portland works. Neither Southeast 16th Avenue nor Southeast 162nd Avenue is in the Central City, but economically they’re in different worlds. Things change over the years, but this has been the case for decades. This is what accounts for the big differences between the “high-rent” and “low-rent” parts of the “outside central Portland” table above.

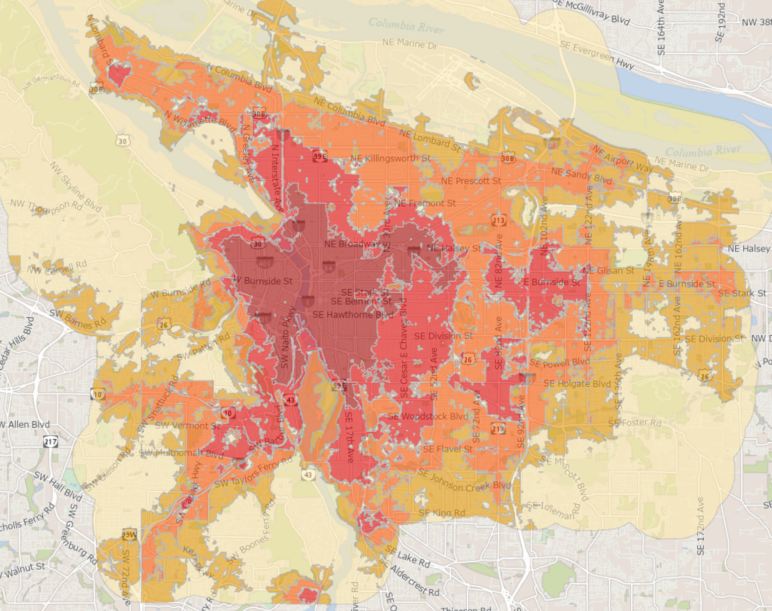

One way to make Portland’s system smarter without introducing needless complexity would be to map the city into three parts rather than two. In fact, the city already has a useful map:

Every five years, the Portland Housing Bureau updates this map of “opportunity” in the city of Portland. Parts of town that are physically close to jobs and have schools with high graduation rates, frequent transit, and other amenities get high opportunity scores (the deepest shades of red in the map above). This score is informed by lots of empirical research (this, for example) showing that the location of our home greatly affects our lives, especially as children. To give more people the choice to live in places they feel are right for them, it makes sense for the city to prioritize below-market housing in the highest-opportunity areas.

These “opportunity areas” also correspond roughly to rent levels—and, therefore, to the viability scenarios for inclusionary housing. Depending on the numbers, Areas 5 and 4 might fall in one category, with the highest tax abatements; Area 3 in a second category; and Areas 2 and 1 into a third.

That would roughly ensure that projects anywhere in town could be fully funded while minimizing waste.

Another possibility for Areas 2 and 1 might be for the city to raise the trigger for its program somewhat, from 20 units to 30 or 35. That would reduce regulatory burden on smaller-scale investments in those areas and reflect the fact that at least right now, there’s not actually a big difference between market rents and “affordable” rents. These lower-opportunity areas mostly need investment, period.

4. Focus it on folks who need it more

Since 2015, when Oregon’s legislature allowed affordability mandates to exist, some have chafed at one of the so-called sideboards the state has imposed: legislators required any such program to let developers comply by building a certain share of homes at 80 percent of the median income.

In Portland today, that means $63,200 for a one-person household and $81,280 for a three-person. Do people making that much money sometimes struggle to afford good housing? Of course. But generally speaking, if you make that much money, you can find a decent market-rate home in Portland, if not a new one. More than half of all homes in Portland rent for less than the rent of a one-bedroom home affordable to someone making 80 percent of the city’s median income.

That’s not the case for someone earning 50-60 percent of the citywide median (e.g., nursing assistants, preschool teachers, clerks, retail workers). That’s approximately the point at which public subsidies start making a big difference to whether people get housed.

A possible solution: Portland can comply with the letter of state law by allowing an 80 percent option without fully funding that option. Almost every developer would choose the fully funded 60 percent option instead. The end result: directing the government’s limited tax abatement dollars to people in more need.

A few things to avoid

Most of the suggestions above are consistent with a letter of recommendations, released on July 28, from the advisory work group I’ve been part of. That letter also recommends some more technical tweaks (like a simpler and more objective way to identify “equivalent” homes) and some suggestions for future work (like a similar math exercise for condo projects, which have all but vanished since the affordability mandate launched and might require a different approach to fully fund).

It’s worth briefly mentioning three possibilities that could unintentionally harm the program and, as a result, the tenants who benefit from it.

- Doling out public subsidy on a case-by-case basis. In theory, it would be very efficient to allocate projects only as much tax abatement as a developer can prove their building needs if it’s going to exist. The trouble is that development math isn’t so clear-cut. A project that pencils in May might no longer pencil in October, or vice versa. This would inevitably lead to guesswork and, potentially, discretionary decisions by city staff or even elected leaders. This might be good for well-connected local developers but it would also be a mess. It might even be better to slightly underfund some buildings than to introduce this much uncertainty.

- Fully funding only big buildings. Big buildings can be great for cities and for neighborhoods, but so can medium-size buildings such as three-story apartment buildings that don’t require land assembly or Wall Street investors. Sometimes you need one or two medium-size buildings before you can get the next big one down the street. Portland shouldn’t go out of its way to juice up big projects at the expense of smaller ones.

- Thinking this is the only policy that matters. Portland’s affordability mandate has been blamed for a lot during its young life. Debate is healthy, but Portlanders shouldn’t let a debate fool them into thinking this mandate is the only reason apartment construction has ebbed, or that fully funding it would be enough to make every new project work.

Fortunately, all these possibilities are easy to avoid if the city wants to.

And despite a lot of drama over the years, that’s consistent with the rest of this program’s calibration. A decade of public debate and a year of mathematical self-scrutiny have come down to a few boring, straightforward steps for local leaders. Portland and Multnomah County should decide what exactly this program is supposed to do; fully fund that mission; and then get on with the rest of their important work.

Comments are closed.