How Oregonians Re-legalized 'Missing Middle' Homes

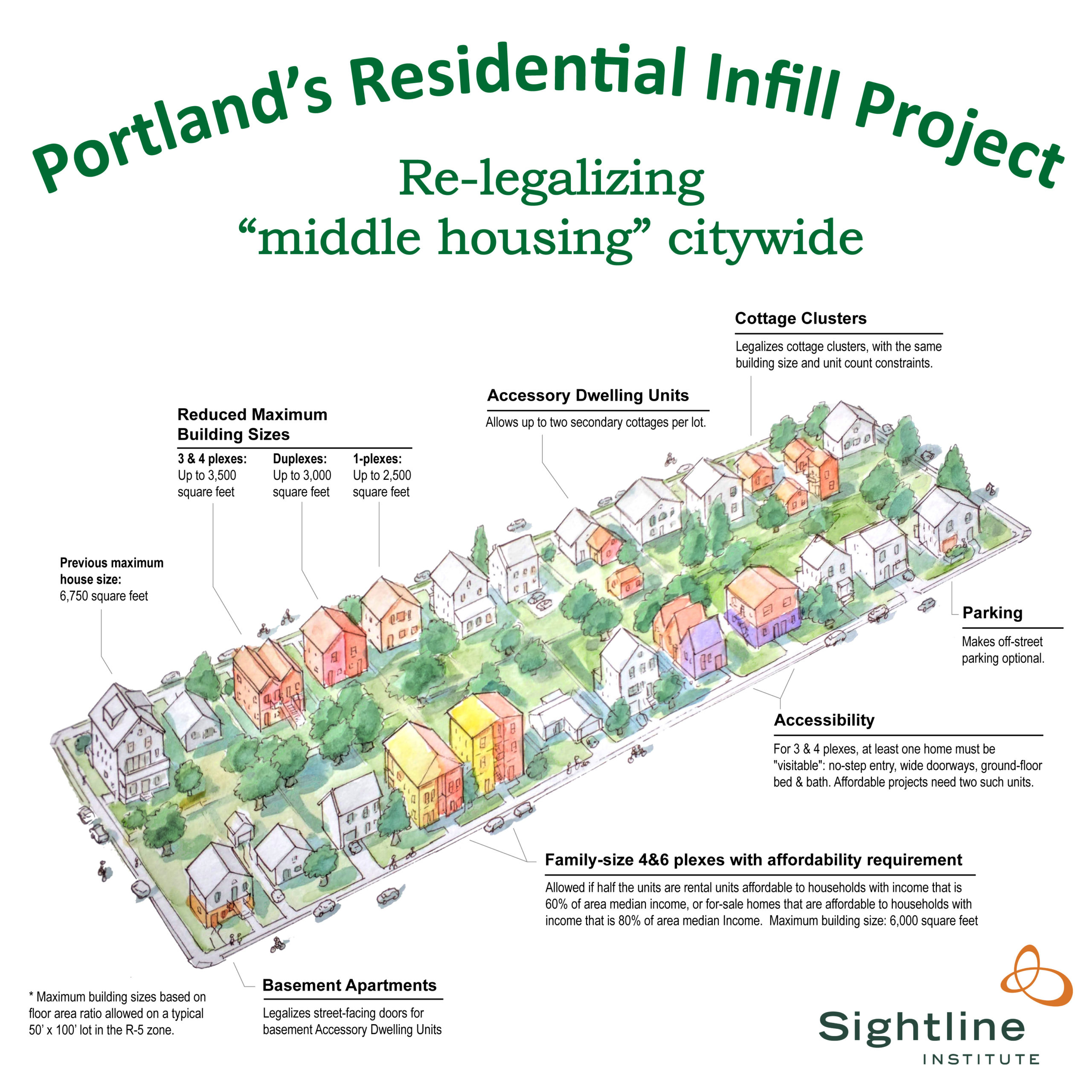

After a seven-year campaign, Portland formally lifted a series of 97-year-old bans on seven different types of homes. Becoming legal on the vast majority of residential lots in Portland: a duplex, a triplex, a fourplex, a mixed-income or below-market sixplex, a large group co-living home, a double ADU, and a tiny backyard home on wheels.

Portland’s reform was the biggest single effect of a state law Oregon passed in 2019, which struck down local bans on these greener, less expensive attached homes in urban areas. House Bill 2001 was the first of its kind in the United States or Canada. These articles explore how it happened and what it caused.

This history was developed in partnership with Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

- We Ran the Rent Numbers on Portland’s 7 Newly Legal Home Options

- The Eight Deaths of Portland’s Residential Infill Project

- How to Tear Down the Invisible Walls in Your City’s Zoning Code

- Eight Ingredients for a State-Level Zoning Reform

- YIMBYism Means Legalizing Very Cheap Homes, Too

- Portland just passed the best low-density zoning reform in US history

After a seven-year campaign, Portland on Sunday formally lifted a series of 97-year-old bans on seven different types of homes.

Becoming legal on the vast majority of residential lots in Portland: a duplex, a triplex, a fourplex, a mixed-income or below-market sixplex, a large group co-living home, a double ADU, and a tiny backyard home on wheels.

Sunday, August 1, is the effective date for a series of reforms passed by Portland City Council over the last 12 months, including most provisions of the city’s “Residential Infill Project” and “Shelter to Housing Continuum Project.” They add up to a dramatic overhaul of the low-density zoning that Portland, like many other North American cities, created in the 1920s.

But today’s milestone comes with an implicit question. All these options may now be legal on paper. But will any of them actually be built?

It was January 2020. One of Oregon’s most respected economists looked over a crowd of 400 people at the state’s annual Housing Economic Summit and told a familiar story about zoning.

Mike Wilkerson, of the consulting firm ECONorthwest, mentioned something he said had happened the previous night: the first city council hearing for Portland’s “Residential Infill Project,” a proposal to legalize up to four homes on almost any residential lot in the state’s largest city. “There were a line of people out the door and the comments were generally revolving around the character of the neighborhood, et cetera,” said Wilkerson.

It was a reasonable story to tell—a story told a thousand times by a hundred years of zoning hearings across the United States, Canada, and around the world.

But Wilkerson was wrong. Somehow, this time it hadn’t gone like that.

These lessons for zoning reformers come from the housing advocates we interviewed about the project’s six-year journey to passage.

- Show, don’t tell. Never allow anyone to encounter a verbal description of the housing being legalized without also seeing a picture of an example. See Lincoln Institute’s book Visualizing Density and Sightline Institute’s public-domain photo library of “missing middle” housing.

- Use language carefully. Avoid “density,” which describes the effect of these policies from a city’s perspective. Instead, frame infill around the benefit to an individual: proximity. Avoid “zoning”—“single-family zoning” sounds both abstract and familiar. Instead, use concrete, colloquial language like “it is currently illegal to build a duplex almost anywhere in Portland.” (For other language tips, see our memo on effective pro-housing messages.)

- Talk about your community’s specific history. Portland advocates tracked down the specific year their city had banned attached homes from most of its land: 1959. Building that year into a pro-housing narrative transformed single-family zoning from “almost-holy abstract concept” into “potentially reversible policy decision.” It also captured some of the class and racial context of exclusionary zoning.

- Avoid pigeonholes. Take advantage of the fact that housing affects everything. Find unexpected interest groups like AARP, public school districts, energy-efficiency companies, business associations and urban foresters to shape nuanced policies and show public officials the variety of benefits that housing can bring. Don’t let any one type of interest group dominate your membership. This makes more people feel welcome joining.

- Meet people where they are. Make a good slideshow. Get on organizations’ agendas. Go to their meetings and answer any questions. Never prematurely assume that anyone will be your opponent. Then find your allies and start to strategize.

- Ally with affordable housing developers. These organizations have the technical expertise, the moral authority and—especially if they own buildable land—a financial incentive to promote better zoning. Organizations that promote homeownership can be an especially good fit.

- Get a neutral body such as the city government to produce analysis most parties can agree on. At their best, hard numbers transform ideological debates into problems that can be solved and tradeoffs that can be balanced. Also, remember that good local analysis depends on deep knowledge of a place. Qualitative analysis, personal relationships and lived experience inform which questions to ask.

- Find common ground by thinking bigger. Advocates of market-rate housing and below-market housing can sometimes find themselves at odds. Should fourplexes be legal, but only for below-market projects? When this happens, the answer may be to unite and ask for more: maybe market-rate fourplexes should be legal, and sixplexes should be legal only for below-market projects.

- Be willing to trade horses. Portland’s zoning reformers found common cause with some NIMBYs by capping the size of one-unit buildings. They found common cause with tenants’ advocates by backing a “tenant opportunity to purchase” program and new rules for screening rental applications.

- The best day to start building a relationship was 10 years ago; the second best day is today. Portland’s process would have collapsed at many points without healthy relationships between many pairs of people both inside and outside of government. You don’t have to be fast friends. You do have to trust that someone is being straight with you, and vice versa. And you have to have each other’s cell phone numbers.

For 100 years, the battles for and against exclusionary zoning have been fought mainly at city halls. There’s a growing sense that they might be the wrong buildings for the job.

Housing shortages spill across city limits, after all, and no one city can single-handedly solve a regional shortage. So what’s in it for any particular city council to shoulder the political costs of trying to end the shortage? Like small countries trying to fight climate change without global solidarity, most city leaders considering joining the fight against a housing shortage will find the political calculus unappealing.

(For a series of smart analyses of this situation and how to fix it, see these articles by law professors Chris Elmendorf, David Schleicher and Roderick Hills, and Alejandro Camacho and Nicholas Marantz.)

State and provincial legislatures, however, are different. Unlike city councils, they have the power to actually solve the problem.

The recipe for solving a housing crisis has various ingredients. But one essential ingredient is simple: Housing has to be legal.

The modern urban pro-housing movement—the YIMBY movement, as it’s sometimes known—spends a lot of effort trying to lift our cities’ widespread bans on mid-cost homes like fourplexes, backyard cottages, and apartments. This movement is increasingly successful, which is great. Legalizing homes of all shapes and sizes in all neighborhoods benefits everyone in cities, even moreso over the long term.

But it might be less obvious that the same principle applies to truly low-cost homes and shelters: villages of tiny homes, recreational vehicles in driveways, group homes, group shelters. Cities should make those options broadly legal, too.

Portland’s city council set a new bar for North American housing reform by legalizing up to four homes on almost any residential lot.

Portland’s new rules will also offer a “deeper affordability” option: four to six homes on any lot if at least half are available to low-income Portlanders at regulated, affordable prices. The measure will make it viable for nonprofits to intersperse below-market housing anywhere in the city for the first time in a century.

And among other things it will remove all parking mandates from three quarters of the city’s residential land, combining with a recent reform of apartment zones to essentially make home driveways optional citywide for the first time since 1973.

It’s the most pro-housing reform to low-density zones in US history.