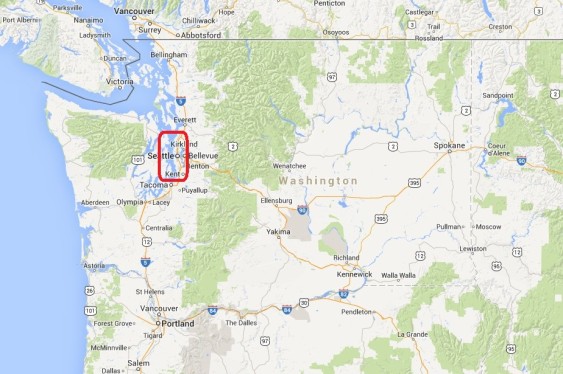

To inform debate over coal exports and oil shipments, Sightline is analyzing public at-grade rail crossings from Sandpoint, Idaho to Cherry Point, Washington.

If fossil fuel companies succeed in shipping the volumes of fuel they have planned, they will—by sheer physical necessity—disrupt vehicle and rail traffic all along the rail route. In this chapter of the series, we examine the effects in King County.

Coal and oil trains—loaded in the interior of North America and bound for the coast—would close off streets for hours each day.

The list of cities and crossings we analyze here is not comprehensive. Rather, we depict several representative locations in King County. In each of these places, we estimate that coal and oil trains would close streets by an average of between 49 minutes and 1 hour and 50 minutes, each day. At the slower speeds that are typical of urban areas, fossil fuel trains could shut down streets for more than 3 hours every day.

Note that these street closures would be in addition to street closures from current trains.

In our last installment, we examined street-rail interfaces in Thurston and Pierce Counties. In this chapter we look at the next leg of the journey as trains roll into King County and reach the city of Auburn.

Auburn, WA: W Main Street, 3rd Street NW, 29th Street NW, and 37th Street NW

Each crossing consists of two tracks and each is separated from street traffic by gates. At least 45 trains pass through Auburn’s crossing daily. Vehicle traffic is highest at West Main Street, with 6,750 average daily vehicles. Near the 29th Street NW crossing (the second from the top), the Emerald Downs horse racing track lies to the west of the railway, while Auburn Municipal Airport lies to the east.

From Auburn, coal and oil trains would continue north to reach Kent.

Kent, WA: Will Street, Titus Street, Gowe Street, Meeker Street, Smith Street, and James Street

The city of Kent is home to six BNSF public grade crossings, each protected by gates. The busiest of the roads, Willis Street, handles 20,200 vehicles on an average day. To the west of the Smith Street crossing (second from the top), the book icon represents the Kent Public Library, and the mortarboard icon represents the Green River Community College – Kent Campus.

Beyond Kent, trains soon reach the SoDo industrial district in south Seattle.

Seattle, WA: S Spokane Street, S Horton Street, S Lander Street, and S Holgate Street

Trains typically slow as they reach the congested streets of south Seattle and begin to disperse to destinations such as the seaport. The mainline BNSF tracks handle 49 trains each day with gates to segment the trains from road traffic. The Spokane Street crossing—beneath the Spokane Street Viaduct, which is elevated—sees 17,350 average vehicles daily. Holgate is classified as a “major truck street” by the Seattle transportation department. The “child crossing” icon at the north edge of the image represents a Head Start facility. (The image above indicates two crossings at Spokane Street because the at-grade crossing actually consists of an east bound street that is separate from the westbound street. At Holgate, we show two crossings because street actually crosses two sets of rail lines.)

Heading north from the SoDo district, trains enter the Great Northern Tunnel that passes beneath downtown Seattle. They emerge on the waterfront in the city’s Belltown neighborhood.

Seattle, WA: Wall Street, Vine Street, Clay Street, and Broad Street

On Seattle’s northern waterfront, the mainline BNSF tracks run alongside a pedestrian and bicycle path and directly in front of numerous businesses. Each crossing is protected by gates and sees 45 trains on a typical day. The highest street traffic here is at Broad Street, with 8,650 average daily vehicles. In the Google image above, it appears that traffic at Broad and Wall Streets is stopped because of a passing freight train.

More detailed analysis of the impact of coal trains on Seattle intersections can be found at:

- Sightline Institute, Why Seattle’s Freight Interests Should Care About Coal Exports

- Gibson Traffic Consultants, traffic study memorandum

- Parametrix, Coal Train Traffic Impact Study

Continuing north through Seattle, coal and oil trains reach the Interbay Railyards before proceeding to the rail trestle that spans Salmon Bay just west of the Ballard Locks.

Seattle, WA: Salmon Bay Bridge

The railway does not intersect with streets in this area, but the bridge must be raised to allow large ships to pass between Puget Sound and Seattle’s freshwater docks along the Ship Canal, Lake Union, and Lake Washington. Heavy fossil fuel train traffic may therefore create an additional complication because trains can only proceed when the bridge is lowered. Coal trains may also present an environmental hazard here, and coal chunks have already been found in the water beneath the trestle.

Northbound trains then travel directly adjacent to Puget Sound, passing through popular parks like Golden Gardens and Carkeek in Seattle and Richmond Beach in Shoreline before reaching waterfront communities in Snohomish County, which we will examine in our next installment.

You can enlarge the images by clicking on them.

Click here for notes, sources, and methodology.

John Abbotts is a former Sightline research consultant who occasionally submits material that Sightline staff turn into blog posts. Thanks to Devin Porter of Goodmeasures.biz for designing the table.

Have photos of a crossing featured in this series? Share them in our “Wrong Side of the Tracks” Flickr pool.

Lawrence

Why couldn’t the coal trains go over the rail line that traverses Stevens Pass and avoid Seattle altogether?

Eric de Place

Good question. The answer, in short, is that coal trains are extremely heavy. They consist of somewhere around 125 railcars each loaded with roughly 110 tons of coal. In order to ascend the grades over Stevens or Stampede Passes, BNSF would have to add locomotives, which increases logistical complications and expense.

As a result, the heavy coal and oil unit trains take the Gorge route when loaded. (There is some debate over whether empty trains might occasionally return over one of the passes, but if they do they will likely be displacing other trains onto the system through King County.)

Philip O.

a extra locomotive seems a lot less complicated then giving Puget sound enviro’s a fight on them home turf.

rail worker

The empties typically go via stevens pass and/or stampede pass. Some of the loads go via stevens when traffic in the gorge reaches a certain level.

Eric de Place

An empty returning via Stampede Pass will still travel back through Seattle to reach the junction at Auburn.

An empty returning via Stevens Pass will, in all likelihood, simply displace another train onto the mainline through Seattle because Stevens Pass operates at or above practical capacity. The traffic congestion effect would be nearly the same.

If coal or oil trains do sometimes transit the mountain pass routes that would reduce the congestion pressure on communities south of Everett. But on the other hand, it raises questions about the rail system’s congestion and traffic impacts on communities along the Stevens and Stampede lines.

I think I speak for almost everyone in the region when I say that I wish BNSF would make its routing decisions more public, so that we can make an informed decision about permitting new terminals. Unfortunately, the corporation has chosen to engage as unabashedly pro-coal advocates, and we’ve caught them in outright deceptions.

Sightline and others are doing our best to provide an honest and fact-checkable accounting of the impacts of coal and oil trains on Northwest communities. We’d be more than happy to correct any error of fact or interpretation in our work, but until the railroads start taking the public interest seriously we’re stuck with what we’ve got.

holdbar

John Norquist, president of the Congress for the New Urbanism, makes the case that freeways have only degraded the value of cities where they’ve been built, and that cities that have removed or avoided building the structures have generally thrived because of it.

http://sf.streetsblog.org/2013/09/20/john-norquist-time-to-talk-about-a-freeway-free-san-francisco/

Seems that a number of long coal trains would also degrade quality of Seattle city life.

Perhaps the coal industry could present how life along existing coal-haul routes has been enhanced.

The Mayor of Neport News, Virginia (home to two large coal export facilities) says the coal piles are unsightly and the coal dust has been covering his city for decades.

http://articles.dailypress.com/2011-07-16/news/dp-nws-cp-nn-coal-dust-20110716_1_coal-dust-coal-piles-coal-terminals

Check out this coal dust fence:

http://weblogs.dailypress.com/news/local/inside-newport-news/2011/08/wind_fence_in_newport_news.html

Have this many long coal trains ever transited an existing large metro area?

CNN’s list of cities with the best quality of life:

Vienna, Austria

Zurich, Switzerland

Auckland, New Zealand

Munich, Germany

Vancouver, Canada

Dusseldorf, Germany

Frankfurt, Germany

Geneva, Switzerland

Copenhagen, Denmark

Bern, Switzerland

http://www.cnn.com/2012/12/04/business/global-city-quality-life/

How many of these cities have coal trains running through them?

I spent a night in Seward, Alaska a few years back and went out to take a walk the next morning. I was shocked at the amount of air pollution. Turns out a Korean coal ship had begun loading that morning. This ship kept it’s engines running – belching out bunker fuel particulate. There was also a cloud of coal dust around the loading operation.

Smog free photos of the North Cascade mountains will be a thing of the past.

Adam

re: Bulk carriers burning bunker in Seward- the reason the ship kept its plant going at the coal pier in Seward is that the electrical grid there can’t power baseload of a ship. The same thing happens when cruise ships or coast guard cutters pull into port there- they run plant at pier for power. Cherry Point could trivially build shoretie power feeds to allow ships to turn down plant.

Wouldn’t do jack to deal with coal dust or traffic disruptions tho.

RDPence

I’ve watched current coal trains operating northbound through SODO, at the Costco store. Always exactly 125 cars (I count) powered by 4 locomotives, 2-3 pulling and 1-2 pushing.

They move at the rate of one car per second, or just over two minutes for the complete train to pass. When the last cars pass Costco, the trains appear to be speeding up, presumably because the head end has entered the tunnel under downtown.

Allowing time for crossing gates to come down and go up, total delay time is about 3 minutes.

Eric de Place

RD, I’m skeptical about your 3 minute figure. Assuming the trains are 7,000 feet long, it implies a train speed of more than 30 mph—and perhaps a lot more if you factor in more time for the gates to go up and down and signals to sound.

When the traffic consulting firm Parametrix evaluated trains in SoDO in 2012, they found that, on average, trains at the crossings were traveling only 7.4 mph (at Holgate) and 8.1 mph (at Lander). In fact, the fastest they clocked ANY train was less than 25 mph. See page 13, here: http://www.seattle.gov/mayor/media/PDF/121105PR-CoalTrainTrafficImpactStudy.pdf.

Regardless, the issue does warrant further study of actual trains at actual crossings. Because of the risk of explosion in the event of derailment, I worry a lot about loaded oil trains traveling at high speeds in urban areas. Of course, if they go slower, as we think they do, that means longer traffic delays.

RDPence

Am just reporting my observations. I agree fully with the civic goal of stopping coal trains, but I want the discussion to be based on truth, as near as we can get to it, and not propaganda, anecdote, or hyperbole.

Debra Rexroat

I live in Auburn, less than 4 blocks from the E-W tracks that come through the gorge, and about 3/4 mile from the Eastern set of N-S tracks, just north of the F Street overpass. I was wondering how I might find out what kinds of cargo are shipped along these lines, how frequently, by whom, and their safety records. I would also like to know where to find out what emergency preparedness, if any, has been planned in case of a derailment or collision in this area, say a 2-4 mile radius from the Auburn rail yard (and the curves and switches here.)

Eric de Place

Ha, ha, ha, ha. Good one!

No, you can have none of that. Neither the railways nor the shippers have any intention of providing the public with even the most basic information about their life-threatening cargoes.

You can, however, ask your local government officials about their capacity to respond to unforeseen railway emergencies. Specifically, ask them how comfortable they feel about putting emergency responders into situations, such as a derailment fire, where the railway won’t reveal the contents on the train. It’s happened before.

If you’re feeling frustrated by any of this, I’d encourage you to take a look at the Oil Transportation Safety Act now before the state legislature: http://environmentalpriorities.org/

Mike W.

It’s going to be a lose/lose situation for everyone that must deal with the additional noise, pollution and interruptions in their daily lives, as if there is not enough stress already. Commuters already are spending a good portion of their lives getting to work on congested streets. I remember the stress it created to see the crossing gates close on you when you were running short on time, just add that to road congestion and bosses with time stamps and you can chalk up just one more struggle to find a reason to smile. Hi Ho Hi Ho it’s off to work we go, happy happy happy, Oops close those bullet proof windows hon, the road rage is getting just terrible at this crossing.