Can a girl get pregnant if she has sex standing up?

Will my boyfriend be able to feel my IUD?

What are dental dams, and why do people use them for sex?

Does everybody shave or trim down there?

If a guy pays for dinner, what does a girl owe him?

If the goal of school is to help kids become healthy, prosperous adults who contribute to thriving communities, then one of the most leveraged classes they can take is sex ed.

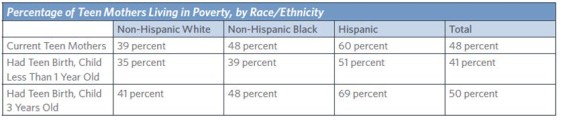

Teen pregnancy is both an effect and a cause of poverty. It can erect insurmountable obstacles for a young woman who may dream of a better life. Of girls who give birth while in high school, fewer than half graduate, and only 2 percent complete a college degree by age 30. Two-thirds receive public assistance in the first year after giving birth—and half are living in poverty three years later. The girls hit the hardest are often those already fighting an uphill battle: black and Latina girls born into impoverished families and hardscrabble communities.

Percentage of Teen Mothers Living in Poverty, by Race, Ethnicity. by The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy (Used with permission.)

Negative impacts of teenage childbearing persist even after accounting for the fact that many teen moms faced challenges before they got pregnant. New media love to tell stories about the exceptions to the rule, the determined young women who fight their way through the obstacles and end up flourishing. Such women provide crucial inspiration for girls who have given birth and need both hope and role models for how to forge ahead.

But the fact is that when girls get pregnant before they’re ready, the odds are stacked against them.

Comprehensive Sex Education

Here’s another fact: Comprehensive sex education that discusses the range of prevention options is one of the most effective tools we have for reducing unwanted teen pregnancy.

In 2008, researchers at the University of Washington compared teens who had received comprehensive sex ed with those who received abstinence-only education or none at all prior to their first sexual intercourse. They found that the kids who received comprehensive sex ed were 50 percent less likely to report a teen pregnancy than those who received abstinence-only education and 60 percent less likely than those who got no sex ed at all. Some parents fear that teaching young people how to prevent pregnancy will make them promiscuous, but data trend in the opposite direction: kids who are taught about pregnancy prevention tend toward later sexual initiation and fewer partners. Sex ed works.

Even so, across the United States, policies and practices are wildly inconsistent, shaped as much by culture and religion as by research. Only 22 states require any form of sexual health education, and only 18 say that such education, if provided, must include information about contraception. As an accommodation to conservative religious sensibilities, 37 states allow parents to excuse their children from any class that addresses sexual health. Worse, in a recent survey by the CDC, 83 percent of girls aged 15–17 said their first formal reproductive health class came after their first sexual contact.

How Cascadia Compares

Big Little Brother Brock by Bekah used under CC BY-NC 2.0

The Cascadia region does better than the American South and Southwest when it comes to teen pregnancy and sexual health education, but even here, standards vary widely.

- Washington does not require sex ed but does insist that when provided, it must be medically accurate. Parents must be notified and given a chance to opt out.

- Oregon does require sex ed, which must be medically accurate. Parents must be notified and given a chance to opt out.

- Idaho has no legal requirements other than the right of parents to opt out of any offerings.

- British Columbia offers comprehensive sexual health education in keeping with national standards. Parents have the right to opt out.

National Research-Based Standards

North of the border, the Canadian government publishes a manual called “Canadian Guidelines for Sexual Health Education.” These guidelines reference international human rights standards, which include the right to sexuality education, and they inform education policy across the country. A set of questions and answers for parents calls abstinence-only education “inappropriate and ineffective.” The Canadian guidelines comprise a “living document,” meaning that they are updated and revised as new research becomes available.

In 2011, a collaborative project called the Future of Sexual Education produced a similar document, a set of National Sexual Health Education Standards for the United States. The project brought together national experts, led by Advocates for Youth, the Answer Program at Rutgers University, and the Sexuality Information and Education Council of the U.S. Their goals (condensed and paraphrased here) were ambitious:

- Outline essential knowledge and skills

- Assist in designing curricula that are evidence-informed, age-appropriate, and theory driven

- Focus on content that is teen relevant and affects high school graduation rates

- Present sexual development as a normal, healthy part of human development

- Translate the emerging research into practice in the classroom

The resulting document has not been endorsed or adopted yet by the federal government. Even so, the ripple effects have been exciting. Last year, following the National Sexual Health Education Standards, the Chicago school system—the third largest in the country—approved a new policy that sex ed should be offered in kindergarten through 12th grade. The curriculum will focus on anatomy and personal safety starting in kindergarten, and sexual health topics from fifth grade on. In May, the sixth-largest district, Broward County, Florida (which also has the country’s highest AIDS rate), used the standards to inform a transition from abstinence only to comprehensive sex ed. Student advocates armed with data and expert opinion led the way.

Expert Educators

Teacher at chalkboard by Cybrarian used under CC BY-NC 2.0

Even with a solid curriculum in place, some teachers are reluctant participants in sex ed, and their students get shortchanged. A Seattle project aims to correct that.

Neighborcare Health is the largest provider of primary care for low-income people in King County, so their staff witness firsthand the challenges faced by young parents. In addition, they manage clinics in three of Seattle’s high schools. Last year Neighborcare hired a full-time reproductive health educator whose job includes fostering conversation in health and science classes, responding to parent inquiries, and providing information to high school students about all aspects of sexual development and health, including new long-acting reversible contraceptives that are now considered top tier for teens.

Janet Cady, medical director of Neighborcare’s school-based clinics, says that young people who talk with the educator then spread what they learn: “Male and female students have engaged with the health educator individually and in group settings. In turn, these youth have expanded accurate health information among their peers and, in many cases, within their families.”

Youth-Friendly Media

Some health advocates are taking youth-friendly messages about sex and pregnancy prevention to the web or the airwaves. Others are working to bring web content and media into the classroom. MTV’s series 16 and Pregnant is back by popular demand, along with downloadable discussion guides from the National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy. Bedsider.org, a funny, smart, award-winning contraception go-to website for youth, gets rave reviews from college and high school students.

http://youtu.be/J7jbo1UeRwE

StayTeen offers age-appropriate information for middle-schoolers, while Hooking Up and Staying Hooked provides candid, playful advice for boys within a framework of mutual respect and safety. SexEtc. has content by teens for teens and features what the site’s editors think are the best sex ed videos on the web.

Peer-to-Peer Education

Savvy educators realize that one of the best ways to reach teens is via other empowered, knowledgeable teens. “I took five different friends to get Mirenas [a type of IUD] at Planned Parenthood in my senior year,” says Jenna, age 19. Jenna had learned about the contraceptive on her own, from a friend. But programs like Planned Parenthood’s Teen Council provide interested girls with training and support so that peers can turn to them as trusted information sources. Teen Council is selective, and girls who get accepted receive 50 or more hours of training about sexual health in the company of—you got it—like-minded peers. They make presentations in their schools and community settings, opening the door for less formal conversations with schoolmates and friends. The program started in King County, Washington, and has spread to eight states.

Shaping the Future

With abstinence-only education thoroughly discredited, evidence-based curricula, candid teen-friendly media, empowered peer counselors, and clinic-school partnerships may be the shape of things to come. Since 1995, May has been designated as National Teen Pregnancy Prevention Month. This May, youth advocates launched a campaign to pass legislation called the Real Education for Healthy Youth Act. Their tools include Washington, D.C., savvy and grassroots organizing (you can sign a petition here), and their goal is to get the National Sexual Health Education Standards turned into law. And funded.

In the meantime, those local, district-level upgrades are touching lives. The Chicago and Broward County school systems together will provide real sexual health information to over 650,000 young people each year. One student in Broward County, Keyanna Suarez, crowed about the change in her district: “There’s not gonna be a taboo about anything. Everyone’s gonna be able to open up, ask questions, and get the info they need to make these decisions because some parents aren’t giving them education at home.”

Next up on the request list from students: honest conversations about sexual pleasure.