As the midterms approach, many American voters may be feeling disenchanted with American democracy. Some may wonder about the point of voting if politicians can gerrymander the districts and big donors can buy elections. While many can identify the bugs in the American system, voters might not know an upgrade is available. It’s called Proportional Representation, and the Canadians might beat Americans to it.

What is Proportional Representation?

Proportional representation (ProRep) is a voting method. For Americans and many Canadians, it’s probably easier to start by saying what ProRep isn’t before explaining what it is. In both countries, most voters are used to the “winner-take-all” method—the person or party with the most votes wins, and everyone else is a loser. Compared to other democracies in the world, this is basically democracy 1.0: winner-take-all, single-member districts with plurality voting.

By contrast, ProRep means candidates and parties win seats in proportion to the votes people cast for them. Forty percent of the vote, for example, equates to 40 percent of the power. ProRep comes in many varieties, but the basic idea is to let voters elect more than one representative at a time in a way that ensures the mix of elected officials reflects the mix of voters.

Most prosperous democracies around the world elect representatives with the ProRep system—it’s democracy 2.0

So what does that actually look like in practice? Imagine Washington State kept its Senate and House the same size—49 and 98 members, respectively. But instead of electing one state senator and two representatives from each of those districts, voters elect four senators and nine representatives using its existing, larger 10 Congressional districts. Voters would rank their district’s candidates by preference and the top four state senatorial candidates would win seats, as would the top nine state representative candidates. Each district would send a mix of representatives to Olympia, representing the mix of voters in the district.

Why would that be better than what voters have now? Progressives in eastern Washington, for example, feel perpetually shut out because they live in districts with opposite majorities, where a left-leaning party or candidate doesn’t stand a chance. But with a proportional system, if about ten percent of voters agreed on a particular candidate, they could elect her as one of the nine state representatives from the district—they get someone who represents their interests versus no one.

READ MORE: Winner-take-all and powers of polarizing candidates

The same goes for conservative voters in Seattle. For example, in Washington’s seventh congressional district, 17 percent of voters chose Craig Keller in 2016. With ProRep, they could have sent a conservative to represent them in Olympia.

Why is ProRep good?

Proportional representation solves or minimizes many of the problems that plague democracy 1.0.

It tames gerrymandering. It is difficult or impossible to gerrymander the lines in proportional districts. With winner-take-all districts, whoever holds the pen can draw districts based on party preferences. Even algorithms aren’t a shoe-in answer. But with ProRep, multiple candidates represent each district according to how many votes each candidate gets. Even if a district leans heavily to one political persuasion, less dominant parties could still eke out a seat, line-drawers be damned.

It helps voters hold representatives accountable. In the United States, two parties dominate political races with increasing polarization. Many voters on one side of the political spectrum feel they could never support a candidate on the other side. Each party has near-monopoly control over the voters that lean their way because, really, what are dissenters going to do? Vote for the other party!? Voters often feel they have no choice. Candidates only have to worry about their party’s primary voters—usually less than one-fifth of voters—and can afford to basically ignore the other voters in their district.

ProRep creates more healthy competition between parties—if a party starts losing voters’ trust, a similar party will rise up to give voters another choice. No seat is safe. Every voter in the general election matters as much as party primary voters matter now. When voters have real choices and their votes matter, both candidates and parties have to stay responsive to more voters.

It loosens big money’s grip on parties and policymaking. If voters grow discontented with one party acting beholden to special interests, they can turn to another party. Because voters have more power to decide who gets into office, big money has less leverage over candidates. Lawmakers in proportional governments have to work together to build majorities to pass policies, meaning they can’t simply attack and tear down other lawmakers; they aren’t slaves to the big money fueling TV attack ads. When money is less decisive in a campaign, it is also less decisive in who moves up through leadership positions. Lawmakers can focus on being good at their jobs instead of being good at dialing for dollars.

Lawmakers work together to create stable, popular policies. Researchers have found that ProRep countries have more stable policies than winner-take-all countries like the United States. That’s because legislators representing a majority of voters have to come together to design a policy that a majority of voters will support. When policies reflect more voices, they tend to stand the test of time. But in the United States, one party representing a minority of voters can ram through a slapdash policy that the other party will strive to dismantle as soon as it comes to power. For example, Renewable Energy Tax Credits are constantly in jeopardy of being repealed and that instability harms clean energy businesses. As another example, the Democrats passed the Affordable Care Act on pure party lines and then the Republicans spent huge amounts of time, energy, and political capital trying to tear it down, again creating harmful uncertainty.

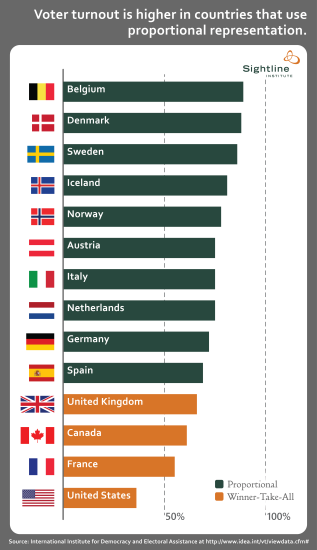

It boosts turnout and participation. Perhaps because they can see that their votes count and that elected officials are accountable to them, more people vote in ProRep countries than winner-take-all countries like the United States. When more voters participate, government is more responsive to the people and the people trust it more.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

Wait, isn’t ProRep bad? Something about Hitler?

Some uninformed commentators claim that proportional representation leads to the rise of extremists like Hitler. They have that wrong. ProRep actually kept Hitler from taking control of Germany. His party won the most votes, which would have handed him the reins in the current American and Canadian system. Thwarted by a fair voting method, he had to seize control through clandestine means. Indeed, scaremongers would do better to worry about winner-take-all voting letting extremists take power. After all, North American voting systems elect Donald Trumps and Doug Fords, who represent minority views.

Where is ProRep used?

Of the 36 Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, just four of them—a mere 11 percent—use winner-take-all systems. Most—nearly 70 percent—use proportional systems.

Hundreds of cities, counties and school boards in the United States also use semi-proportional systems to great success.

Why does PR matter for the environment?

Cascadian voters care about the environment—they want to take action on climate change, to stop oil trains and pipelines, to increase housing affordability, and to be able to get to work and play without polluting. But when voters’ voices aren’t heard, legislatures don’t take action on the issues that matter.

Countries with proportional systems respond to what voters want. For example, proportional countries use more than twice as much renewable energy as do winner-take-all countries, largely due to policies promoting renewable energy use. Proportional countries have slowed their carbon dioxide emissions more than four times as quickly as winner-take-all countries, largely due to policies aimed at slowing global climate change.

When voters care about the environment, and legislators care about voters, legislators care and pass policies that voters can be proud of.

Why don’t we do campaign finance reform and automatic voter registration to fix democracy instead?

We should definitely do those too! We at Sightline believe every citizen should have:

- The right to vote, meaning states should honor and protect the right to vote by keeping voter rolls up-to-date, rather than encumbering the right to vote by forcing voters to bring forms of ID they might not own to the polls. Oregon led the nation by becoming the first state to implement automatic voter registration, a common-sense measure to modernize elections.

- The right to an equal voice in government, meaning their voice should not be drowned out by big money in politics. We believe that Honest Election Seattle’s democracy vouchers are leading the way in this realm.

- The right to equal representation, meaning proportional representation, rather than outdated, distorted, winner-take-all.

ProRep is not a silver bullet, but it could go a long way to improving the functionality of North America’s democratic institutions.

Is “proportional” basically the same as “parliamentary”?

No. “Proportional” has to do with how legislators are elected. “Parliamentary” has to do with how the head of government is selected.

In a proportional system, voters elect legislators from multi-winner districts with a method that ensures seats in the legislative body (parliament or legislature) reflect all the voters. Because most voters are able to choose a lawmaker who represents them, voters’ voices are heard in the halls of government. In non-proportional systems, voters elect legislators from a single-winner district with a winner-take-all method. Many, sometimes most, voters don’t have someone they voted for representing them in the capitol.

In a parliamentary system, the legislature selects the head of government, usually called the prime minister. In contrast, in the United States, the electoral college selects the president.

Many western European countries, including Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden, are both proportional and parliamentary. The United Kingdom and Canada are not proportional (they use winner-take-all elections) but are parliamentary (legislators select the prime minister). The United States is not proportional (it is winner-take-all) and not parliamentary (the electoral college selects the president). The United States could become proportional without becoming parliamentary.

John Whitmer

The bar graph showing the relation between countries and voter turnout not only says something about voter turnout, it also shows what an outlier we are with respect to more rational voting methods. Sightline is to be highly commended for continuing to encourage more democratic procedures in much of our election systems.

Kelly Gerling

Thanks for writing Kristin!

I think MMP or STV with a unicameral, parliamentary system are simpler, more effective, more democratic systems for states and for the nation than confusing multimember districts.

However, whatever we choose in terms of PR, what remains is how to use the elusive but obvious procedures of direct democracy to implement PR— like MMP, STV or multimember voting—and the structural enhancements of democracy in a unicameral parliamentary system—pronto.

We need to start in California, Oregon and Washington, and at the national level simultaneously, all under the strategy banner of a political revolution.

This cannot be done via any existing government. It can be done directly by We the People via direct democracy procedures at the state and national levels.

Right? Or not right?

And what are the steps to take for full implementation in WA, OR and CA, and nationally?

What is our grand strategy for democratizing the American ruling establishment oligarchy?

Jameson Quinn

Great article. You did a lot of things exactly right:

* Covered the main advantages of ProRep.

* Called it “ProRep”, because “PR” is impossible to google.

* Debunked the silly “Hitler” attack.

* Distinguished it from parliamentary government.

But your definition of ProRep is a bit too narrow. Multiseat districts are one variety, but there are other varieties which keep single-seat districts. The key idea of ProRep is that similar voters are grouped together to avoid wasting their votes. (There’s a good way to show this graphically: look up “Sankey” or “alluvial” diagrams.) Those groups must be able to cover wider areas than just one district, but you can still use single-member districts to simplify ballots and ensure regional as well as ideological fairness, as in PLACE voting: https://electowiki.org/wiki/PLACE_FAQ .