As the midterms approach, many of our American readers riveted to US races may be wondering why Sightline is so focused on a referendum happening in British Columbia. If you want to know what proportional representation is all about, we answer your questions here. If you are wondering what the referendum in British Columbia is all about and why you should care, read on.

Why does Sightline care about British Columbia?

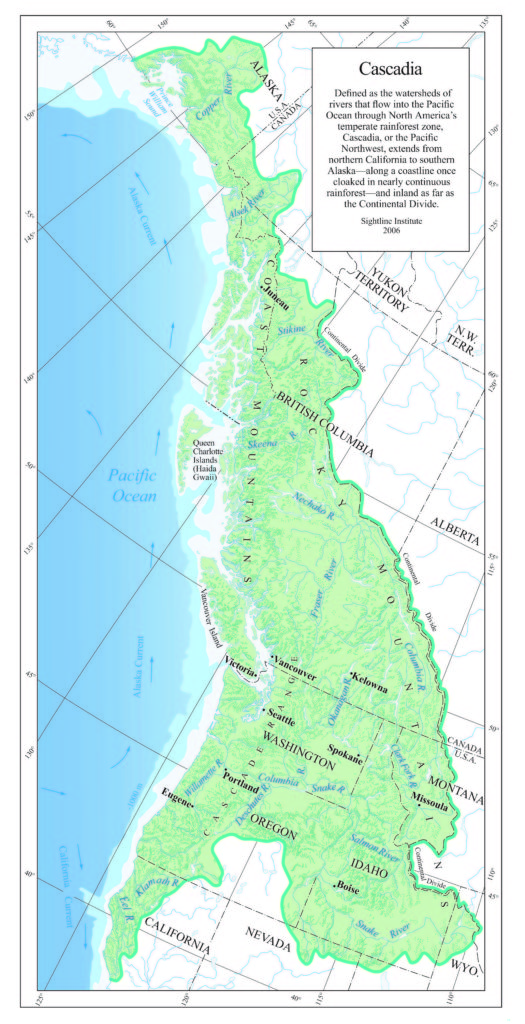

Because it is part of Cascadia!

No matter state or national borders, Sightline Institute serves the bioregion of Cascadia, also known as the Pacific Northwest, also known as North America’s temperate rainforest zone. The region spans from Alaska to northern California, including much of British Columbia, Oregon, Idaho, and all of Washington State. National and state boundaries don’t always follow the watersheds and ecosystems that hold a region together.

Map drawn by Cynthia Thomas on the basis of forest data in Conservation International, Ecotrust, and Pacific GIS, “Coastal Temperate Rain Forests of North America,” Portland, 1995. See also, David D. McCloskey “Cascadia,” Cascadia Institute, Seattle, 1988.

In many ways, the border is the biggest difference between British Columbia and Washington and Oregon. As far as environment and politics go, they’re quite alike.

Why should American voters care?

Americans are seething over—and victim to—partisan gerrymandering, and it’s pretty clear Congress, the Supreme Court, and/or algorithms can’t fix it. Voters are disillusioned with politics and with both parties, and some are getting wise to the fact that democracy 1.0 and its system of single-winner districts has bugs. They might not yet realize that democracy 2.0, proportional representation (ProRep), is already in use around the world. A few American commentators, including Lee Drutman, David Brooks, and Rick Hertzberg, have been trying to wake Americans up to the news about ProRep. If British Columbia can make a province-wide change, it could light the path for US states to do the same.

If British Columbia adopts ProRep, people all across Cascadia (and beyond) could see its benefits in action: it makes more votes count, holds elected officials more accountable, and results in more thoughtful and popular legislation getting passed. People in Oregon and Washington may feel some commonality with lush and chilly New Zealand, so its story of breaking free from its colonial roots in the 1990s and switching to ProRep holds weight. But if seeing an example of ProRep working in the actual Pacific Northwest, might inspire adoption of democracy 2.0 below the 49th parallel.

ProRep isn’t a panacea for all that ails American democracy, but it’s a good start. It repels gerrymandering. It saps special interests’ influence. It elects legislative bodies that better reflect voters. It makes more votes count, which makes more legislators accountable to the voters. It shifts campaigns from empty put-downs to serious solutions. And it leads to more thoughtful, durable, popular policies that don’t see-saw after every election.

How are BC elections, politics, and parties similar to those in US states?

Canada and the United States are both former British colonies, and both inherited an outdated method of electing their legislatures—single-winner districts with First Past the Post (FPTP) voting. This method is sometimes known as winner-take-all because, each district gets just one candidate to represent all constituents, even if more than half voted for other candidates. In both British Columbia and the states, voters elect legislators by district every two or four years.

In both places, single-winner districts are vulnerable to gerrymandering. Both British Columbia and Washington State (along with other American states) have tried to solve gerrymandering with independent or bipartisan redistricting, but both have discovered that committees and algorithms can’t solve “safe” winner-take-all districts. When a district is drawn with a tilt toward one party or another, that party’s candidate can safely win—voters from the other party have no hope of electing a representative.

Winner-take-all districts usually reinforce two-party dominance. While the BC Green Party won a few seats in the most recent election, the two major parties—BC New Democratic Party (left-leaning) and the BC Liberals (right-leaning)—usually win all or nearly all the seats. Two-party dominance leads to the government see-sawing between opposing sides, each of which might gain power in any given year with a mere minority of votes. Voters for the losing side (even if their side actually won more votes) feel locked out of government until the next election.

Most developed countries have figured out that winner-take-all voting leads to all sorts of mischief, including partisan gerrymandering. And they have abandoned it in favor of proportional representation. So far, Canada, its provinces, and the United States have mostly stuck to the old ways.

Translate ‘Canadian’ for me

| Canada | United States |

|---|---|

| Province | State |

| Riding | District |

| Legislative Assembly | State Senate and House combined into one body |

| Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) | State representative or state senator |

| First-Past-the-Post (FPTP) | Plurality voting, or winner-take-all (the form of voting Americans and Canadians are most familiar with) |

How are they different?

There are a few key differences between British Columbia and Washington or Oregon:

- Although two main parties dominate BC politics just like in the states, third parties sometimes win a few seats in the province. For example, the BC Green Party has three representatives out of 87 right now.

- BC provincial parties are not always the same as national parties. In the US, a Democrat is a Democrat in both Washington State and Washington, DC. In Canada, a BC Liberal candidate is a center-right candidate (akin to a Republican) but Trudeau’s national Liberal Party is a center-left party, more like an American Democrat.

- British Columbia has a parliamentary system. Voters in Washington and Oregon directly elect governors to serve as Head of State and Head of Government. In British Columbia, the leader of the party or coalition that wins the majority of seats in the legislature becomes the Premier (currently John Horgan) and serves as the province’s Head of Government.

- British Columbia has just one legislative body, not two. Washington and Oregon each have a House of Representatives and a Senate, two legislative bodies representing the same people and passing the same bills. British Columbia has a more streamlined system with one 87-member Legislative Assembly.

None of these differences change the problems that both Canadians and Americans face with winner-take-all voting.

Why is British Columbia voting on ProRep?

Canadians in general, and British Columbians in particular, have been toying with the idea of ProRep for more than a century. “Wrong-winner” elections, such as the 1996 election in which the BC NDP took control of the Legislative Assembly with fewer votes than the BC Liberal Party, happen often and make voters see that outdated First-Past-the-Post voting isn’t fair. When more than half the voters in a riding (district) didn’t vote for the MLA (representative) who supposedly represents them, their voice isn’t heard. And when 17 percent of BC voters choose Green candidates but BC Greens hold just 3 out of 87 seats, some voters feel like their votes don’t matter as much as someone else’s.

For all these reasons, BC voters keep trying to switch to ProRep. In 2005, 58 percent of voters chose ProRep, but the politicians in charge set the threshold at 60 percent. Voters tried again in 2009, and it failed. In 2017, both the NDP and the Greens promised the people a chance at electoral reform, and they formed a coalition government and delivered on their promise. The result is the referendum that will take place between October 22 and November 30.

What exactly are they voting on?

Later this month, BC voters will get a vote-at-home ballot asking them two questions:

- Should British Columbia use First Past the Post or Proportional Representation?

- If ProRep, which of these three options do you prefer?

The three options are:

- Mixed Member Proportional (MM)—a tried and true method used in Germany, New Zealand, and several other countries

- Dual Member Proportional (DMP)—a simple, familiar ballot with a more representative result

- Rural-Urban PR—gives voters more control by letting them rank their favorite candidates

If you want to know more about the options, you can see our explainer here and we also came up with some easy-to-understand cartoons to explain each option.

Richard Lung

Unfortunately, your so-called “democracy 2.0” system has a fatal bug in it, that incapacitated its inventors ranked choice for voters and left it in the hands of party list makers. This BC referendum three even recognises the necessaity of a ranked choice, to sort out its three infelicitous options, while denying ranked choice in those options.

Even tho the BC government had to resort to low cunning to do so. It mutilated the ranked choice PR recommended by the BC Citizens Assembly, by forcing-in its favorite system, MMP, for rural areas.

BC is a health to democracy warning from the three rigged referendums. All three parties turned BC away from the democratic voting system, making way for the kakistocratic voting system.

(Editor:)

John Stuart Mill: Proportional Representation is Personal Representation.

The Angels Weep: H. G. Wells on Electoral Reform.

(Richard Lung:)

Peace-making Power-sharing;

Scientific Method of Elections.

Science is Ethics as Electics.

FAB STV: Four Averages Binomial Single Transferable Vote.

(in French) Modele Scientifique du Proces Electoral.

Wayne Smith

1. All proportional systems give voters the power to hold politicians and political parties accountable.

2. Under the RUP option offered in the BC referendum, most BC voters would use the Single Transferable Vote, a proportional system with ranked ballots.