Oregon legislators took a historic leap toward greener, fairer, less expensive cities Sunday by passing the first law of its kind in the United States or Canada: A state-level legalization of so-called “missing middle” housing.

If signed by Gov. Kate Brown in the next month, House Bill 2001 will strike down local bans on duplexes for every low-density residential lot in all cities with more than 10,000 residents and all urban lots in the Portland metro area.

In cities of more than 25,000 and within the Portland metro area, the bill would further legalize triplexes, fourplexes, attached townhomes, and cottage clusters on some lots in all “areas zoned for residential use,” where only single-detached houses are currently allowed.

Or, as some more dramatic headlines have summarized it: The bill bans single-family zoning.

Bipartisan support in a deeply divided state

House Bill 2001 legalizes fourplexes somewhere in every low-density area of large cities—for example, on corner lots.

HB 2001 sailed through the House two weeks ago by 43-16, with two-thirds of both the Democratic and Republican caucuses in support. On Sunday, after reconvening from a last-minute Republican walkout that killed a major cap-and-trade bill and also nearly derailed this vote, the Senate followed, 17-9. (The Senate party split was 14-4 in the Democratic caucus, 3-5 in the Republican caucus.)

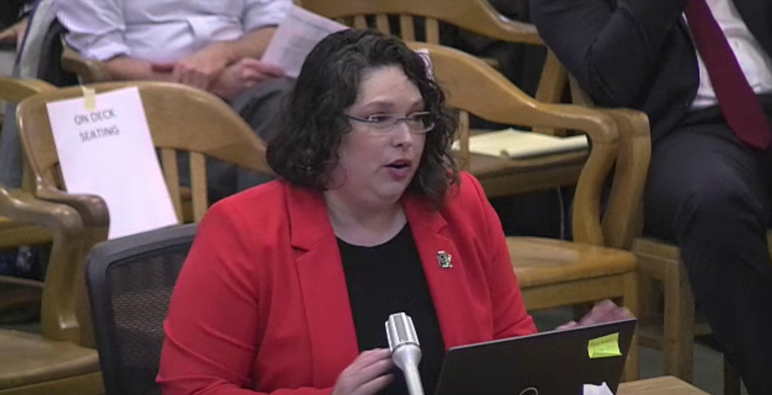

“This is about choice,” said Rep. Tina Kotek, the Democratic speaker of Oregon’s house and the bill’s architect and lead champion, when she introduced the bill in February. “This is about allowing for different opportunities in neighborhoods that are currently extremely limited.”

“We all have an affordable housing crisis in our areas,” said Rep. Jack Zika, a Redmond Republican who supported the bill before a different committee June 11. “This is not a silver bullet, but will address some of the things that all our constituents need. … We have an opportunity now for first-time homebuyers.”

About 2.8 million Oregonians live in jurisdictions affected by the bill. Of those, about 2.5 million live in larger cities and the Portland metro area where up to four homes per lot would become legal; the rest, in mid-size cities where only duplexes would be legalized.

Cities would retain the ability to regulate building size and design, giving them leeway to ensure that change will be gradual. Cities also have flexibility to incentivize projects that create new below-market homes. (Portland, which has been working on its own fourplex legalization for the last four years, is planning to do exactly that, using a sliding scale of size bonuses that lets buildings be slightly larger for each additional home they create, and another bonus if one or more of the homes is offered below market price.)

“Opening up the American Dream”

Marisa Zapata, a land-use planning professor at Portland State University, gave lawmakers a primer on the history of zoning when HB 2001 was introduced in February.

Smaller, attached homes like duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes, attached townhomes, and two-story apartment buildings were legal throughout most cities until the mid 20th century and remain common in cities of every size, but building more of them was gradually banned from most land in most cities during the era of legally enforced segregation and the rise of auto-oriented development.

Those bans have led to cities sharply divided between two relatively expensive housing types: apartments in tall buildings, and houses on large lots.

The situation makes no sense, Marisa Zapata, a Portland State University land-use professor, told legislators at the bill’s first hearing.

“We’ve ended up without a rational basis for a zoning code that has single-family on one extreme and multi-family as a high-intensity … dense use,” Zapata said.

Instead, Zapata praised “the idea of trying to integrate duplexes, triplexes, skinny homes, ADUs and cottage clusters into the fabric of single-family homes, hopefully opening up the American Dream to more people.”

House Bill 2001 would help more mid- and lower-income families achieve homeownership, said Steve Messinetti, CEO of the Portland-area chapter of Habitat for Humanity.

In Portland, Messinetti said, his nonprofit organization builds homes mostly on the tiny patches of land where duplexes and triplexes are still legal. He said sharing land is the only way to get development costs low enough to serve “folks making $30,000 to $40,000 a year who are doing everything right but just can’t afford a place to live.”

“There’s a lot of builders out there who want to do good and want to make the sort of houses people need, but you just can’t make a 1,000-square-foot home pencil on a $200,000 piece of property,” Messinetti said.

Habitat and other nonprofit affordable housing developers, coordinated by the Oregon Housing Alliance, became early and crucial backers of the bill.

Some opponents warned of “wholesale redevelopment,” others of no effect

The bill also drew plenty of opposition: for example, from Joe Dudman of Eastmoreland, a close-in enclave that was one of the first Portland areas to ban attached housing.

Today, Zillow puts Eastmoreland’s median home price at $733,000, thanks in part to a beautiful public golf course and a recently built light-rail line nearby.

“HB 2001 will encourage wholesale redevelopment of existing neighborhoods, and the eventual elimination of most single-family houses,” Dudman wrote to legislators in one of 292 pieces of testimony formally submitted to the bill’s committees since February. “Quality of life will plummet.”

Also in opposition was the city council of Eugene, which passed a resolution explicitly opposing the bill; a city staffer wrote, “we do not believe HB 2001 will result in more units on the ground.” The Oregon League of Cities, a group whose lobbyist Erin Doyle said will generally “avoid preemption of local authority with everything we have,” pushed against the bill, too.

On the other side were AARP of Oregon, which said middle housing makes it easier to age in place; The Street Trust, a transportation group that argued HB 2001 would let more people live near good transit and walkable neighborhoods; 1000 Friends of Oregon, which said the law would advance the state’s long fight against exclusionary zoning; Pablo Alvarez of Lane County NAACP, who said the bill would start to undo some of the ways racism has undermined housing affordability for all; Sunrise PDX, which called energy-efficient housing an essential way to fight climate change; and Portland Public Schools, which described the bill as a long-term way to reduce school segregation.

“There is ample research to show that student outcomes improve when schools are more balanced by race/ethnicity and income,” wrote the school district’s lobbyist, Courtney Westling.

(In case it’s not obvious, we at Sightline were among the supporters, too.)

Bans on attached housing: “a thing of the past”

Townhomes, attached to at least one other home across a lot line, are one of the “middle housing” options legalized in all urban residential areas by HB 2001.

Oregon’s Sunday vote puts the Pacific Northwest clearly at the front of a multinational movement to improve affordability, equity, and sustainability with reform to urban zoning—especially low-density areas.

Duplexes were declared legal on 99 percent of residential lots in Vancouver, BC, last September. Tigard, Oregon, legalized courtyard apartments, cottage clusters and de-facto duplexes on almost every lot, plus fourplexes on almost every corner, in November. On Monday, Seattle seems likely to legalize up to two accessory dwellings, each up to 1,000 square feet, on every lot. And the City of Portland could pass its city-level fourplex legalization by the end of 2019.

Cascadia’s progress is part of a larger wave. Minneapolis legalized triplexes on every lot last fall; that inspired Charlotte, North Carolina to consider the same. In California, where one secondary cottage is already legal on almost every residential lot in the state, Assembly Bill 68 would raise that to two. Earlier this month, the New York Times dedicated a long, reported Sunday editorial to supporting such proposals to re-legalize these options for lower-density living.

In the end, this issue is less complicated than most land-use questions, said Deborah Kafoury, chair of the Multnomah County Commission, in her February testimony endorsing the bill.

“Oregon is a great state to live; we have a lot of people who are moving here; we don’t have enough housing for them, so the cost of housing skyrockets,” Kafoury said. “House Bill 2001 addresses this challenge head-on by allowing more homes to be built in highly restrictive neighborhoods.”

“I am lucky enough to live in one of these single family homes in one of these neighborhoods, and I understand the impulse to want to preserve it,” she went on. “But it’s time to accept that single-family zoning is a thing of the past. Because restricting where people live by virtue of their income has never been OK. It shouldn’t be OK now.”

Michael Andersen, senior researcher, has been writing about ways better municipal policy can help break poverty cycles, with a focus on housing and transportation, for over a decade. His work before joining Sightline included reporting and editing for print and web in Longview and Vancouver, WA, and Portland, OR, where he worked as news editor of BikePortland.org; writer for the pro-housing coalition Portland for Everyone; and infrastructure staff writer for PeopleForBikes, the largest national biking advocacy organization. He has an English degree from Grinnell College and a journalism degree from Northwestern. Find his latest research here. If you have questions or would like to make a media inquiry, contact Sightline Communications Associate Kelsey Hamlin.

Bill Hall

Why can’t some of these HUGE HOUSES old & new be divided into multi family? In the sixties I had an aunt of Dad who lived in a VERY NICE OLD HOUSE in the Irvington area that had been converted into a duplex. It was still outside but inside was much neater.

What I am seeing now is there will be more suspicious fires in certain areas and lots of rental properties being totally neglected. I really don’t see where this is going to lead to lots more affordable housing .

Michael Andersen

Because it was illegal to do so! That internal division was almost certainly completed before Portland banned middle housing from most of Irvington.

Not for long, though.

MikeG

Seems like a pretty immediate solution for housing and rental shortages. I was just talking to a A developer who mentioned that it costs so much to build in LA&OC California that it only makes sense to target the high end/luxury segment with new construction – at least for single-family homes.

IDK what the economics for new-construction of apartments is like, but I have to image its similar. Certainly more constructive than Governor Newsom suing Huntington. ref: https://abc7.com/society/gov-newsom-suing-huntington-beach-o…

reply

Michael Andersen

The more units per acre, the lower your land costs per unit are. So if land costs are super high, apartments are the cheapest option, even though they have higher construction costs per square foot.

Middle housing, though, is the best of both worlds in a lot of cases. You get to divide the land costs several ways but you still get to use the cheaper-per-square-foot wood-frame construction. So it can keep delivering homes even in markets where wages aren’t high enough to support either apartments or detached homes.

Michael G

Mr. Andersen is incorrect. It is *not* true that the price of land is fixed. Adding more housing units per acre spreads the land cost among more apartments *but* the price of land goes up with the expected increase in income negating the “units-per-acre” supposed advantage. If it were otherwise, apartments in NYC and Hong Kong would be very cheap – they are not.

“Bid-rent” theory (dating from 1809 – by the English economist Ricardo) states that the value of a property depends on the income that can be derived from it. If you increase the rents that can be charged for a property by putting more apartments on a property then it is worth more to the buyer and the price of the property increases. In this case that means that if a property is suddenly allowed to double or quadruple the number of dwelling units on it, the price of the land will go up accordingly. “Bid-rent” is taught in AP Geography to HS students. Do a search on “bid-rent theory AP human geography” and you will get plenty of links – including Wikipedia.

Typically, nearness to the center of business (CBD = Central Business District) increases a property’s potential income but so can good schools, nice parks, a quiet pleasant environment. If that changes, if the parks get too crowded and dangerous, the schools show fewer graduating or going to college, then the area becomes less desirable, rents decrease, land becomes less valuable. Once a neighborhood starts to decrease in value it causes a stampede out of the area as no one wants to be the last to sell.

Commercial and apartment property evaluations are always done both by “comparable sales” for similar lands and by “bid-rent”. They should be in agreement but not always. If “comps” are higher than “bid-rent” it means buyers expect rents to go up.

If the local schools are particularly good, then the new dwellings will be correspondingly more expensive since that is what people are willing to pay up for. For that reason, this new law will not help poorer families move into richer neighborhoods.

Michael Andersen

Michael, I think most empirical analyses show that in growing/job-rich cities, the land value per unit generally drops as unit count per acre rises, despite that countervailing force you mention.

https://www.buildzoom.com/blog/paying-for-dirt-where-have-home-values-detached-from-construction-costs

Would you pay as much for a 1,000 square foot duplex unit as for an otherwise comparable 2,000 square foot oneplex on the same block? If not, then I think it’s fairly clear that duplexes offer an opportunity for families to buy into neighborhoods they otherwise would not be able to afford.

Michael G

You can certainly lower unit costs in the very short term by making each unit smaller. However, if you increase the density of an area over the long term you increase the cost of land because there are more people competing for the same land. The highest bidder wins and housing prices increase along with the land costs. If you think fitting more dwellings on an acre will lower costs, take a look at Mountain View or Cupertino in Silicon Valley where an 1800 sf townhouse costs $1.8M and a 1,000 sf TH costs $1.2M. That is what you will get in Portland if you keep increasing the density.

You really need to address why land in places like NYC and Hong Kong is the most expensive in the world before you argue for increasing density.

The “BuildZoom” link you provided agrees with that by talking about *zonable* land. They are referring to protected land like parks and preserved open spaces. Increasing the density of existing land does nothing to increase the amount of zonable land.

Portland always comes up in academic discussions of “Urban Growth Boundaries” because Portland was one of the first large cities to create an UGB. The result of limiting land use is the remaining land increases in value. I am not arguing against UGBs but if Portland claims there is “housing crisis” they need to consider that to some extent they created it by limiting the amount of zonable land.

In addition, the Portland Metro Area is growing very fast with more high-paid techies coming in all the time from around the world. They can outbid the locals and “displace” them. Increasing urban density to accommodate them gets you Silicon Valley prices in addition to the displacement.

Michael Andersen

If Cupertino is an example of dense development, then our disagreements are broader. This street is two blocks north of Apple HQ:

https://www.google.com/maps/@37.3385459,-122.0104916,3a,60y,105.93h,84.27t/data=!3m6!1e1!3m4!1sx8yGDlEs7oe9PoBUrffs7w!2e0!7i16384!8i8192

I’ll quote the Buildzoom piece:

“For upzoning to meaningfully suppress housing prices, it must be applied en masse. Upzoning a limited number of lots – where “limited” means small compared to the relevant housing market – will raise the value of the upzoned land without measurably influencing home values. To suppress housing prices, upzoning must substantially ease the scarcity of zoned units and, for this to happen, upzoning must be applied at sufficient scale vis-a-vis the relevant housing market.

The expensive coastal cities have no shortage of land per se, but of zoned units. Such units can be thought of as slots for households to stake a claim in a location, or call it home, allowing them to live in the area and access its job market. It is these slots whose scarcity is drawing a premium in the expensive coastal metros, reflected by inflated land values, whereas land per se is not in short supply. The San Francisco Bay Area, for example, whose shortage of zoned units is most acute, spanned 1,386 square miles as of 2010 and housed about 8 million people. That is enough land to house 75 or 100 million people at the average densities of Paris or Manhattan, respectively,”

Michael G

You showed a neighborhood in Cupertino with single family homes. I could show you virtually identical neighborhoods in 4 of the 5 boroughs in NYC. The streets were designed with that many houses in mind. If you increase the density beyond what it was designed for, traffic will become (even more) impossible. Places where it has been increased are clogged all day – not just at rush hours. Half the population wants to leave because of the high prices, the other half because of the traffic.

If you eliminate single family housing in places like Cupertino and Mountain View what will happen is that the engineers who keep Facebook-Apple-Netflix-Google going will simply move.

They might move to another part of the SF Bay but more likely they will move to Denver, Austin, Raleigh, Charlotte, Dallas, etc. which is where people are moving anyway. People want a SFH and will do what it takes to get it. If you mess up their neighborhoods with too much traffic and parking problems they will leave for where the traffic and parking isn’t as bad. Maybe that is what will happen to Portland.

The city planners at San Jose said there are several areas that are not possible for future development. People simply cannot get in or out now in any reasonable time and greater density will make it intolerable. They also determined it is not financially possible to build high rise housing because high rise construction costs too much and rents aren’t high enough.

With the jobs dispersed everywhere and no central job center like Manhattan, bus routes are shrinking because they just don’t go where enough people need to go. So ridership is declining everywhere even though they are 91% subsidized – a $2 bus ticket gets $20 added from the county.

Most of the SF Bay area land is a fire hazard or very hilly protected open space – mostly both. The flat land is built up or pretty inaccessible except in San Jose. Take a look at the aerial map near the bottom of

http://meetingthetwain.blogspot.com/2018/06/commute-distance-in-us-metro-areas.html

For example, look closely at where the Golden Gate Bridge is on Marin. Whenever anyone says we can build in Marin I ask where they would fit another GG Bridge. (The current bridge has been at capacity for at least 10 years.) That closes the discussion. It wouldn’t violate the laws of physics to build a second bridge or extra level but it would cost a fortune to expand access through the granite hills. Ultimately you need to ask why you want to do it. Is the US so short of places to build?

The reason there is so much protected land in the other Bay Area counties is because it is too hard and dangerous (fire hazard “red” colors in Summer) to build on. The value is much lower than flat easily built on land. That made it relatively easy to purchase for state parks, and fire zones – basically people gave it away or sold it for a song because no one wanted it.

Simply adding up the land areas of the counties does not tell you the real story.

Yet again I ask “why, if density lowers rents, are NYC and Hong Kong so expensive?”

You should look up “optimal city size”. There are over 1,000 academic articles on it. Cities can’t grow forever. Manhattan’s population peaked in 1915 at 2.4M. It was 1.6M last census. Everyone moved to the fields of Long Island. Sprawl is inevitable and the only way to get cheap housing.

Michael Andersen

It’s not density that lowers rents. It’s keeping up with population growth. Increasing density is one of two ways to do that; the other is sprawl.

New York City has been building quite a bit of housing, to its credit, but it’s still very expensive in part because its suburbs ban attached housing and have barely added any homes in the last 30 years despite massive wage and job growth in the city.

I don’t know Hong Kong very well, but I assume one of the main reasons is that its suburbs haven’t grown much, because they’re in mainland China and people are mostly interested in living in Hong Kong proper.

If you want an example of rising density allowing housing growth to keep up with population growth, and thus keeping prices stable, the best example in the world is probably Tokyo.

eric

I appreciate the interplay between you two. You both make valid points and it’s encouraging that you don’t need to disparage the other the make your point. Keep the conversation going ;)”

William J. Jackson

This is a good step, however I feel it needs to be fine tuned so that these new houses are sold to new occupiers, and not to a corporation with an empire of units for rent. Such empires are in fact businesses and should be taxed as a business in EACH CASE the same business taxes are added to the annual costs, as if they were a small shop selling widgets. An absentee landlord = business tax added, a BNB = business taxes added for each month it acts as a BNB. This would act as a powerful price moderation influence. Here in Toronto there is a severe problem with Chinese buyers with cash to buy houses and condominiums. Many of these sit vacant. Taxed as businesses, there would be pressure to sell or for the owners to occupy them.

Powerful, low cost software suites have made it a simple management task to run these empires of separate homes/condos as if they were a single high rise unit

Dave

It’s too bad your city doesn’t seize some unoccupied investment houses to declare public housing. Property rights are very nice in their place but damn, it would be a bitch to scrunch down into the appliance crate that my doctor might ultimately have to use for her office.

Dave

I will suggest the most politically incorrect thing possible here–that this could push some property values down, and that that would be a very good thing. What nobody wants to either acknowledge or talk about is that there must be a point when the state steps in and twists the arm of the market either to directly limit the selling and renting price of properties or to “nudge” with legislation that might make some locations feel less valuable. I think we will ultimately have a choice between a command economy in housing and favelas, and I don’t think favelas are the more reasonable choice!

Michael James

Property markets don’t work like that. In fact you have it inverted. In the developed world (and even most of the developing world) the most crowded places have the most expensive real estate. Think Manhattan-NYC, or San Francisco (second most dense city in US), London, or Paris (densest big city in the west), not to mention Hong Kong, the most expensive real estate in the world. Do you really believe any of these places are favelas? Of course there is the good, bad and the ugly among these examples but they all support the conclusion that densification increases the value of property–a lot.

Dave

Then, it really is time for states and cities to intervene in markets, institute command pricing and hard ceilings on home values and rents. Also, as a little nudge, time to stop allowing publicly funded police services to be used for evictions. The market is not a natural thing–it goes where power wants it to go.

Todd Boyle

I am so grateful to the Legislature for HB2001. Eugene was incapable of sharing the available land and still hasn’t complied with SB1051 allowing ADUs. I’m sure Eugene will drag their feet on this one, too. We have 36,000 people living on less than $1000/ month, and record levels of homelessness and displacement.

Eugene has 1/3 of its population living below $25,000/ year. Thats 60,000 people. That’s 30% of Area Median Income. Yet our City Council has done nothing but block any sort of infill, and enact dozens of barriers against any form of cheap housing. The *wide* majority of legislators approving HB2001 shows how weird the Eugene city council is. They still haven’t even complied with the ADU law that was effective last year. Eugene’s response to the homeless and displaced, largely caused by their own anti-housing ordinances, has been more police. The City and County don’t even operate a homeless shelter here.

David

One of the strangest lines of logic in this article… “Because restricting where people live by virtue of their income has never been OK.” I’d argue that it has always been okay and is normal in a country with individual property rights. That is exactly why we have different housing in different locations with different amenities.

Duncan McEwan

Once again “choice” is what the Democrat majority defines it to be. What if those seeking affordable housing prefer a single family home? Wouldn’t it be better to raise the minimum wage in large metropolitan areas to match the cost of housing, costs that have been exacerbated by the Urban Growth Boundaries. Choice for those doing the cleaning for Pearl District residents is a six to ten story building on a MAX line. Pay them enough that they have the financial ability to choose.

Michael Andersen

Fourplexes will almost certainly be cheaper per square foot than apartments in six to ten story buildings, on or off the MAX.

Amy L Turnbull

Thank you for posting this article. I’ve been following ADU development in Portland for years and support missing middle housing. However, I am concerned there is no oversight written into HB2001’s language to prevent tear downs. Part of Portland’s allure is it’s old houses. Am I missing something or is there no mention of just how missing middle housing will be sighted in existing neighborhoods of historical buildings? What will prevent a developer from tearing down an existing home that might be shared among 2-4 in order to build a missing middle development or a cottage cluster that houses more families aka units? From a developers point of view, more units equals more money. Is this bill a threat to Portland’s character? Will the old homes simply disappear?

Michael Andersen

Amy, I think this is a totally reasonable concern.

The first thing I’d say is that for better or worse, this isn’t likely to lead to rapid or dramatic transformation of our neighborhoods – just one lot here, another there.

https://www.sightline.org/2019/06/21/this-is-what-a-street-looks-like-39-years-after-legalizing-fourplexes/

The second is that your concern also applies to the status quo … the difference isn’t whether or not small one-unit buildings in fancy areas are being replaced, it’s whether the building that replaces them is designed for one millionaire household or several middle-income households.

https://medium.com/@pdx4all/every-month-portlands-infill-rules-aren-t-changed-the-city-looks-more-like-this-23686e1b9179

Third, you are probably familiar with some big old homes that have been internally divided into multiple apartments. This bill not only re-legalizes that practice (currently illegal, except in the case of a single ADU, in most of Oregon) it also adjusts some building codes that have made that practice infeasible. This creates new ways to make an investment in an old structure pay off – which will hopefully result in more attractive but run-down old structures getting new leases on life.

https://medium.com/@pdx4all/1-house-4-homes-dekum-project-shows-the-potential-of-stacked-flats-fb7ff77e392b

Finally, I understand the assumption that “more units equals more money” because I used to share it! But I’ve learned, since starting to research this, that this isn’t really the case. The thing that really does equal more money is building *size*. Increasing number of kitchens that are allowed to exist on a lot isn’t inherently valuable, in part because kitchens are expensive to build per square foot! What a unit-count increase does is allows more households to divide the cost of the land among themselves. Since the land accounts for 1/3 to 1/2 of the cost of many homes in Oregon’s higher-cost areas (Corvallis, Hillsboro, Portland), splitting it two, three or four ways saves a lot of money per household—so much that newly built homes can come out to the same final price as an old run-down home of the same size and still be profitable for the builder. (Meanwhile, big nice old homes in good condition aren’t profitable to tear down and replace. They’re most valuable just continuing to do their thing as long as the structure is in good shape.)

https://www.sightline.org/2019/02/13/who-would-live-in-missing-middle-housing-the-middle-class/

Note that none of these answers address the separate, but important, question of creating below-market homes for people who need them, especially in exclusive areas. We need other tools, notably including public subsidies, to achieve that! And we should create them. But that’s not really the same issue as the structural preservation question.

Amy L Turnbull

“One lot here, one lot there…” is fine as long as there are no homes being razed to create these lots! I’ve been following Stop Demolishing Portland on Facebook and have seen some beautiful houses well, demolished! Do we assume that all houses to be demolished are not structurally sound? Or is that developers have more to gain to build a new fourplex where once there was one that would not pencil out (kitchens aside)? Where in the bill or what guidelines will be created to determine what is disposable to create one lot here, one lot there? Or do we leave it to the discretion of the developer? You say: “It isn’t whether or not small one-unit buildings in fancy areas are being replaced, it’s whether the building that replaces them is designed for one millionaire household or several middle-income households.” This conquers up the image in movie “Dr. Zhivago” of the peasants dismantling the beautiful home to fuel their fires! To their credit, they divided up that big beautiful house into apartments–they didn’t build a new one! I’m just hoping policy makers put in place provisions to protect these old houses if they are structurally sound! Don’t leave it up to developers! Divide them, yes, but please keep them intact! I just feel like developers won’t find it cost effective to do so and will pull them down willy nilly.

Finally, the definition in the bill is unclear to me. In some places it reads “town houses” and in others “fourplexes” etc. Let’s hope we all know what we will be getting with this bill so we can reimagine Portland 30 years from now and it will look very similar to what we already have, minus ugly structures like the one on 4021 NE 7th! Reducing size will not address aesthetics so again, I ask, what guidelines, what other language is there in the bill to guard against tear downs and ugly, somewhat smaller buildings?

Michael Andersen

I may be wrong, but I strongly suspect that any intact, attractive houses highlighted on SDP were demolished for significantly larger apartment buildings. That’s not what we’re talking about here.

If a developer has more to gain from a oneplex, then (even once fourplexes are legal) they’ll build a oneplex. If they have more to gain from a fourplex, they’ll build that, if they’re allowed to. Seems as if the question is: which would we prefer?

As for definitions, the bill says larger jurisdictions like Portland have to allow that entire menu of options, without unreasonable restrictions, in every low-density area. What’s “unreasonable”? That’ll be up to the administrative boards and courts to hammer out.

The bill doesn’t preempt local design preferences for the good reason that aesthetic preferences will vary by community. Oregon law *does* require all design regulation to be subject to objective standards that don’t add unreasonable costs; that’s for the also good reason that we don’t want the aesthetic preferences of comfortable people to interfere with our ability to produce enough homes to keep up with population growth.

Rose

I found this concept quite interesting. We could use it where I live. I live on the Florida West coast. In our city, new construction consists of multistory buildings where a one bedroom apartment is $1850 a month and a four bedroom is $4,000 a month. Affordable Housing is a huge issue with minimum wage at $8.12 an hour. The people that work downtown cannot afford to live there. Many live in lesser expensive areas and drive up to 1.5 hours one way to work. Rush hours are a mess. Public transportation is 20 yrs behind and they tell you to ‘bike’ to work, One has to laugh.

Daveq

You make a brilliant case for command pricing of housing using the power of the state.

Many parts of the country have housing cost emergencies–unfortunately, no local or state government have the courage to attack it forcefully and directly. The housing market needs affordability forced onto it by government. It can’t matter what tradition, law, the constitution, or how hard someone has worked for their property anymore. We need new laws for new reality. Regulate housing prices!

Benito

Command pricing = fascism