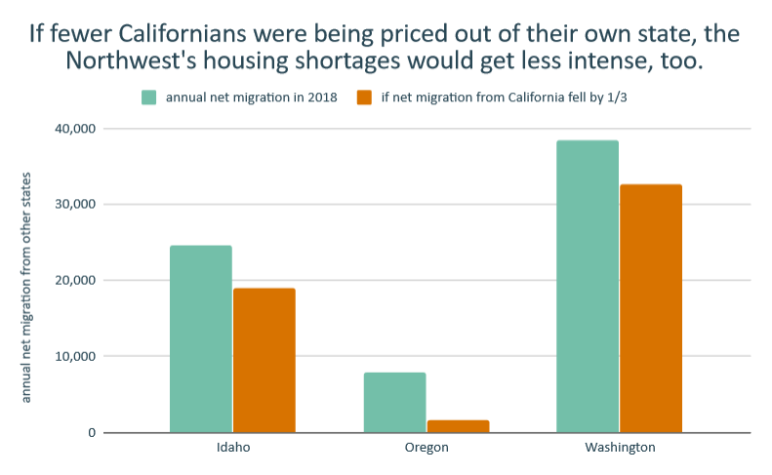

California’s repeated failure to strike down local bans on close-in housing has an incalculable number of victims. But 13 million of them live in Oregon, Washington, and Idaho.

Year after year, through booms and busts, California sends a one-way jet stream of people moving north to Cascadia. If comparable numbers of people were instead able to flow in both directions, those Northwest states would find it much easier to build enough homes to keep up with population growth.

That’s especially true in Oregon, which gets one of the nation’s most lopsided inflows of people from California. If net migration out of California were to drop by 33 percent across the board, Oregon’s overall net population growth from domestic migration would fall about 80 percent.

California cities aren’t the only ones whose invisible walls of exclusionary zoning have created a housing shortage that spills across state lines. But California’s effects on Cascadia show why the collective failure of local governments to allow housing can demand national action.

Data from US Census Bureau. Image: Sightline, republishable under our free use policy.

Last week, as California’s fourth consecutive year of extreme wildfires forced another round of evacuations from its ever-sprawling exurbs, California’s legislature rejected yet another bill that could have dramatically reduced the state’s shortage of homes.

Senate Bill 1120 would have legalized duplexes on almost any owner-occupied urban residential lot in California and—maybe even more importantly—allowed the same lots to be split in half. That’d essentially allow up to four homes on most such lots. (Lots currently or recently occupied by tenants could have been developed too, as long as the tenant-occupied home wasn’t removed.)

Re-legalizing these small-scale options across the most housing-scarce US state could have added up to big results. A July study from UCLA had estimated that broad fourplex legalization would make it financially feasible to add 1.2 million more homes to California—about half of the frequently cited estimate of the state’s chronic shortage, 2 to 3.5 million homes.

Californians, most of whom seem to favor housing legalization and who are blessed with a persistent and creative squad of vehemently pro-housing organizers and lawmakers, have every reason to be upset. But so do many millions of people outside the state—maybe more than anyone else, those of us in Cascadia.

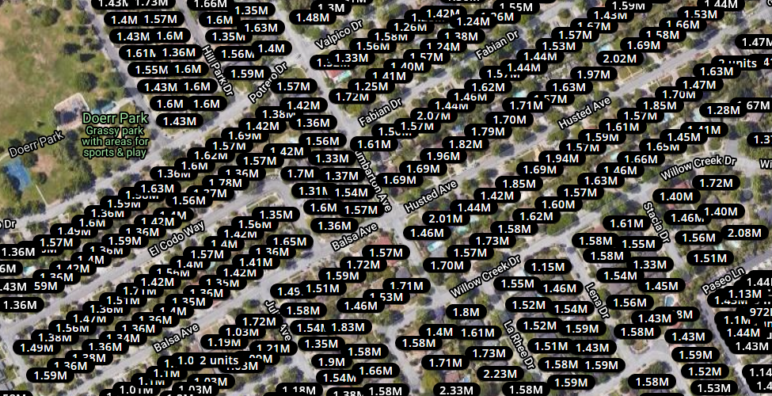

Many former Californians seem to be fleeing home prices

Home prices in San Jose. Image: Zillow.

Every year, more than 100,000 people migrate from California to the three states that might be most similar to it: its three closest neighbors in the Pacific Northwest.

It’d be a perfectly healthy flow of people and their ideas if a comparable number of people were moving the other way, too. But these days, 60 years after California’s last big population boom, that’s not how things work. Only half as many people—just over 50,000 in 2018, according to the Census Bureau—move to California from Oregon, Washington, and Idaho.

Who are these people migrating from California? Many are, of course, moving for work, school, or family. Others may be fleeing California’s worsening climate, or maybe even its politics. But data suggest that many are home price refugees. In Oregon, and to a lesser extent in Idaho and Washington, migration from California is concentrated among lower-income and younger people.

And who could blame them? California’s home prices are bonkers, and only getting higher.

One in five rentals in the state goes for more than $2,000 a month. The median owner-occupied home costs $546,800. Of the nation’s 10 least affordable metro areas by ratio of median home price to income, seven are in California. (So is the 11th: Fresno, whose sprawling suburbs are facing an “unprecedented disaster” this week from the Creek Fire.)

This is what it looks like when most of an entire state stops building anywhere close to enough homes for year after year. It creates a cruel game of musical chairs. With too few chairs, everyone ends up paying dearly, but the richest are always the ones who get to sit down first.

The poorest, meanwhile, end up living on the street or hitting the road. Or they might still be stuck at home in Baton Rouge or Bangkok, unable to relocate to a place where a better life might await them if only the first and last month’s rent weren’t inconceivably expensive.

The federal government could do something

When a state problem spills across a state’s borders—or, in the case of California land use, thousands of local problems do—it’s time for the federal government to see what it can do.

There are legitimate reasons for the federal government to tread lightly. Housing reforms that would work in San Jose may not work in St. Joseph, Missouri. But there are also reforms that make sense anywhere, like re-legalizing smallplexes and making driveways optional.

In an age when domestic migration has fallen to economically dangerous lows, when exclusionary zoning is a crucial force behind the 30-year re-segregation of American schools, and when Gulf hurricanes are sucking wildfire smoke all the way across the Great Plains, national leaders should get to work figuring out what they can agree on.

As I wrote last year, there’s been a rapid shift in the national politics of housing abundance. As my colleague Dan wrote last week, there are already good bills in Congress. Congress could incentivize states to pass laws like Oregon has, or directly reward cities and counties that allow more homes. Local advocates have been floating data-driven methods for identifying exclusionary neighborhoods that could be built into laws, administrative rules or judicial review.

What’s missing, so far, is a chance for Congress to vote.

David J Feldman

There must be hard ceilings on both rents and the selling price of all properties. Market forces are failing and need a heavy state hand to direct them.

Kevin Withers

This authors viewpoint does not reflect reality. The appreciation for the single family home neighborhood is an appreciation that is held throughout America and is not a California trait. The politicians in Sacramento who want to attack one lifestyle over another…? Well that’s an entire issue in itself, and the thrice failed SB50 speaks loudly. SB1120 was an attempt to sneak through legislation during the pandemic, without full discussion or scrutiny. That’s yet another disingenuous tactic of the small group of ‘advocates’, to use a polite description. Fact: population growth in California has peaked, and the false number tossed around about a ‘massive shortage” is refuted McKinsey nonsense. If you want a path forward, the divisive actions of legislators like Scott Wiener need to be abandoned. Try consensus & persuasion over push-polls and developer funded lobbyists perhaps?

Michael Andersen

If desire to live in California had peaked, home prices would be falling. They are not. Population growth in California has nearly stopped because so many Californians are not even willing to allow enough homes for their own children to live in, let alone everyone who would relocate to the state if they could.

Nobody is attacking the decision to live in a single-detached home. The problem is that the status quo zoning in California and elsewhere forbids people from living in attached homes if they want to.

Neil Bhateja

While California is losing people due to domestic migration, it’s population is still increasing due to international immigration. This post only concentrates on the domestic flow, and implies California isn’t doing it’s part to house people, but another way to look at it is that the state is taking on a disproportionate responsibility of taking in America’s immigrants, and it would be almost greedy to build the housing to hoard all that dynamism. When Californians move to other states, it’s not California pushing their problem onto other states, it’s *our* problem, America’s problem.

Michael Andersen

Good point about the role of international immigration, but I don’t think it implies that California doesn’t have a housing shortage, or that its shortage isn’t harming people in other states.

Presumably most of the many immigrants arriving in California and living there long enough to be counted by the Census would prefer to make their homes in California. I agree that most states would probably benefit from their presence, but I don’t think people are toothpaste — squeezing California isn’t going to direct pressure reliably toward any one goal. The people might not immigrate to the US at all, or they might end up much worse off if they try to head elsewhere. The same might be true of the domestic outmigration from California.

It is indeed America’s problem, not just California’s, that California isn’t building enough homes. I guess we agree about that.

Debra Buckley

it is a problem in the cascades with losing wildlife, more crime and rising housing and property taxes and costs, making it harder for the natives, not to mention the homeless Californians pooping on our streets and throwing their trash everywhere, California needs to stay home and work on California. Other States are being flooded with California Problems and soon the solution will be Overcrowding, Higher Taxes and No Jobs for any of them, so Yes, the Federal Government needs to work on the problem.

Michael Andersen

To be clear, Debra, that’s not at all my argument here – as an Oregonian (who grew up in Ohio) I welcome Californians to come to Oregon and the Northwest if they want to! Both states are stronger for it! The problem here is that California is so expensive that almost nobody is moving in the other direction. That’s the way to have a healthy balance of cross-migration.

Debra Buckley

that is also true, however, most californians leaving are choosing to live in the Pacific Northwest. Why? not just housing prices, no, they want our Pacific Northwest for the Nature, and a better life, but now our quality of life is overcrowded, Wildlife getting hit by Cars or relocated altogether so Yes it is hurting our Eco-System.