In the United States, the candidate who wins the popular vote may not become president. That has happened in two of the past six elections.

“The national popular vote is the single-most effective way to reform our democracy at the state level.” Mike Foote, Colorado State Senate.

You may think it’s because of the Electoral College, but that’s not the whole story. The Constitution gives states the power to decide what to do with their Electoral College votes. As it stands, most states have chosen to give all their Electoral College votes to the candidate who wins the most votes in their state. But they could do it differently. In fact 15 states and DC have signed on to the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact—instead of giving all their votes to the candidate who won the most votes in their state, they would promise to place all their Electoral College votes behind the presidential candidate who wins the most votes nationwide. The compact would only take effect—and it only works to flip the whole country from the Electoral College count to a popular vote count—when enough states sign on; amounting to over half of all 538 Electoral votes. That is, it would need participating states’ electoral votes to total 270; currently it has 196.

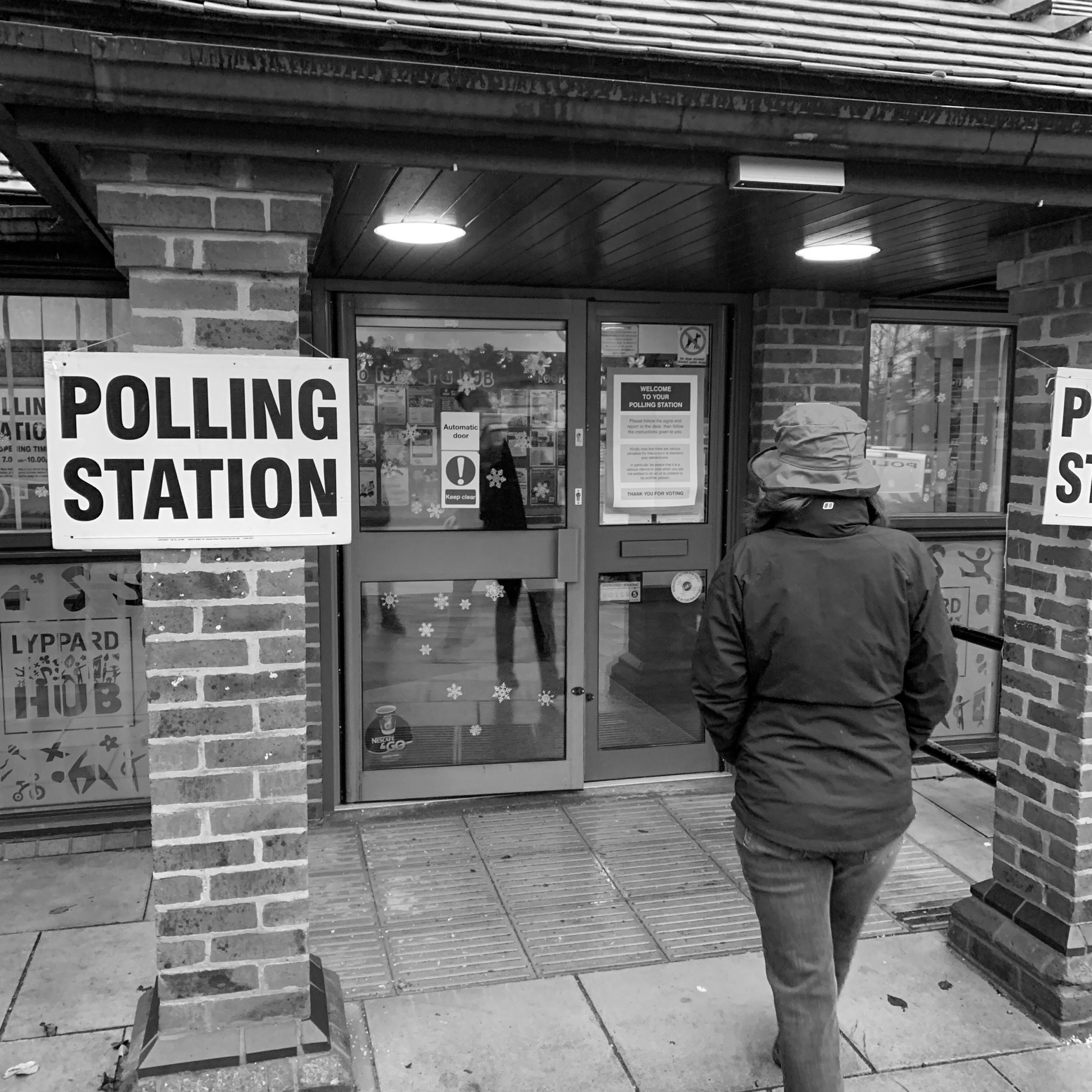

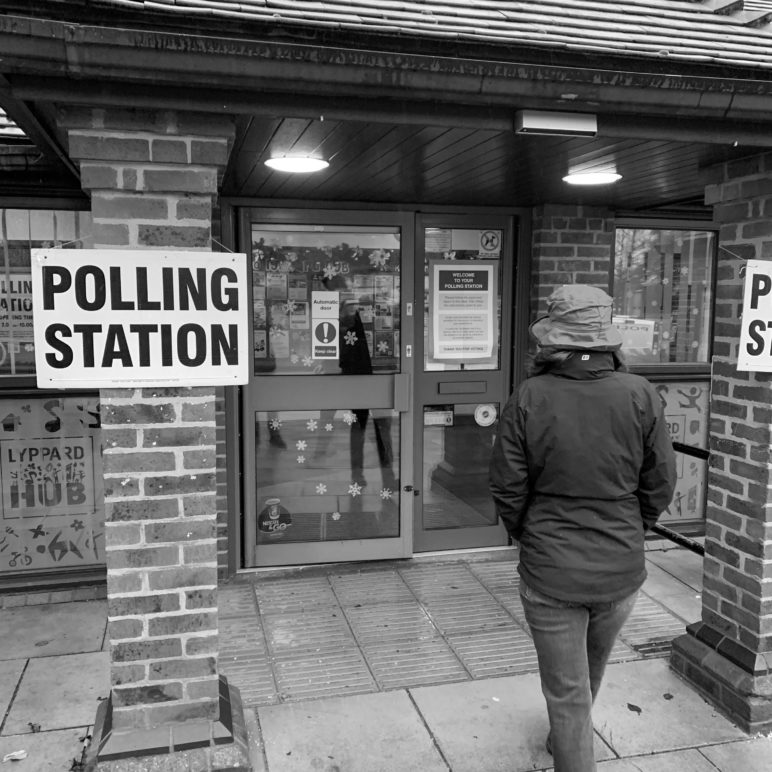

Colorado’s lawmakers joined the Compact in 2019. But opponents hope they can peel Colorado off and stick with the current state-winner-take-all method even if the Compact gets to 270. This November, voters in Colorado will have the chance to decide whether Colorado should stay in the compact or back out—a “no” vote means stay in, and a “yes” vote means back out. It’s a move that would slow the Compact’s progress to override the Electoral College and shift power to voters without requiring a Constitutional amendment.

States haven’t always assigned all Electoral votes to the candidate who won the most votes state-wide. Each state’s legislators determine how to distribute that state’s Electoral College votes. And in the 19th century, motivated to maximize partisan power and back preferred parties, states adopted the winner-take-all set-up we’re used to now. Virginia, as one example, switched to the winner-take-all method in 1800 to favor home-state candidate Thomas Jefferson’s chances nationally. More and more states, afraid to lose advantage, followed suit in the next two decades.

A downside for voters—and democratic representation—is that the current system essentially disenfranchises Republican voters who happen to live in a “blue” state—say, Washington—and Democratic voters who happen to live in a “red” state—say, Idaho. It also creates a massive imbalance in the value of a single vote, depending on where the voter casts their ballot, rendering votes most important in a handful of swing states, which just happen to be about evenly split between Democrats and Republicans.

As a result, presidential candidates spend the vast majority of their campaigning time focused on a handful of states, where votes truly count. In 2016, presidential candidates made 228 stops in just four states and spent 94 percent of their campaigning in 12 states. They totaled 24 visits for the rest of the 38 states. One analysis concluded that a voter in Wyoming is three times more powerful than one in Washington, four times more powerful than one in Oregon.

Determining Electoral votes based on the national popular vote “turns the entire country to the battleground state for America,” says Eileen Reavey, national grassroots director at the National Popular Vote.

Determining Electoral votes based on the national popular vote “turns the entire country to the battleground state for America,” says Eileen Reavey, national grassroots director at the National Popular Vote, a group pushing for states to join the interstate compact. And in the past few years, more state lawmakers have questioned the current system that relegates most voters to the sidelines, minimizing the battlefield to just a handful of battleground states.

With Colorado’s nine Electoral votes, the compact has enough states to total 196 electoral votes. (Washington and Oregon have already signed onto the compact and provided 19 of those votes.) Nine other states, making up a total of 88 electoral votes, have passed the bill in at least one chamber. If those states jump on board, the compact would have well over the 270 Electoral votes it needs to determine the next president based on the national popular vote.

Opponents of the Colorado bill got enough signatures to place an option to repeal the law on the November ballot. They’ve deployed many of the arguments Sightline has dispelled about the national popular vote: Claiming it would give small states less power. (Swing states, both big and small ones, are the ones that have a voice. All other states are mostly ignored.) They say it would make it impossible for a Republican presidential candidate to win. (The numbers of registered voters nationwide are essentially a 50-50 split between Democrats and Republicans.) And, they assert, rural voters would be given less of a voice. (In the current system, rural voters only in certain key swing states have a voice. Rural voters in Washington, for example, don’t really have a say in the state’s Electoral choice.)

Colorado State Senator Mike Foote, who sponsored the Senate bill, said the current system leads to presidential campaigns that cater to a small group of Americans in a small number of states—and poor governing once they enter the White House. Battleground states receive, on average, more federal grants and twice as many presidential disaster declarations, according to the National Popular Vote.

President Donald Trump’s campaign attack on mail-in ballots provides another example of the lack of attention on non-battleground states. While Washington, Oregon, and Colorado have conducted all vote-by-mail elections for years, the practice garnered little attention from the Trump campaign—and its lawyers—until swing states began to offer widespread mail-in voting during the pandemic.

Foote says the governing system needs a lot of fixing, but many of those changes must happen at the federal level. But the Electoral College system is one in which states are uniquely positioned to be able to prompt a change, he says.

“The national popular vote is the single-most effective way to reform our democracy at the state level,” Foote said. “The presidential election is one that’s actually determined at the state level. It’s a state-based system that requires a state-based solution.”

Sightline Institute is a 501(c)3 non-profit organization and does not support, endorse, or oppose any candidate or political party.

Hayat Norimine, research contributor, is a freelance writer who grew up in Washington on the border of Idaho. She previously covered city halls and politics for The Dallas Morning News, Seattle Met magazine, and The Daily News in Longview, Washington. She has an MA in journalism from the Medill School of Journalism and a BA in English from the University of Washington. For Sightline, she researches and writes about democracy reform and elections issues and reports on fossil fuel proposals along the Thin Green Line.