Alaskans voting in the 2020 general election no longer need a witness signature to vote absentee. The court-ordered change will likely prevent the disenfranchisement of hundreds of voters. It’s an encouraging sign in a state that has left unexplored many options for accommodating record numbers of absentee voters.

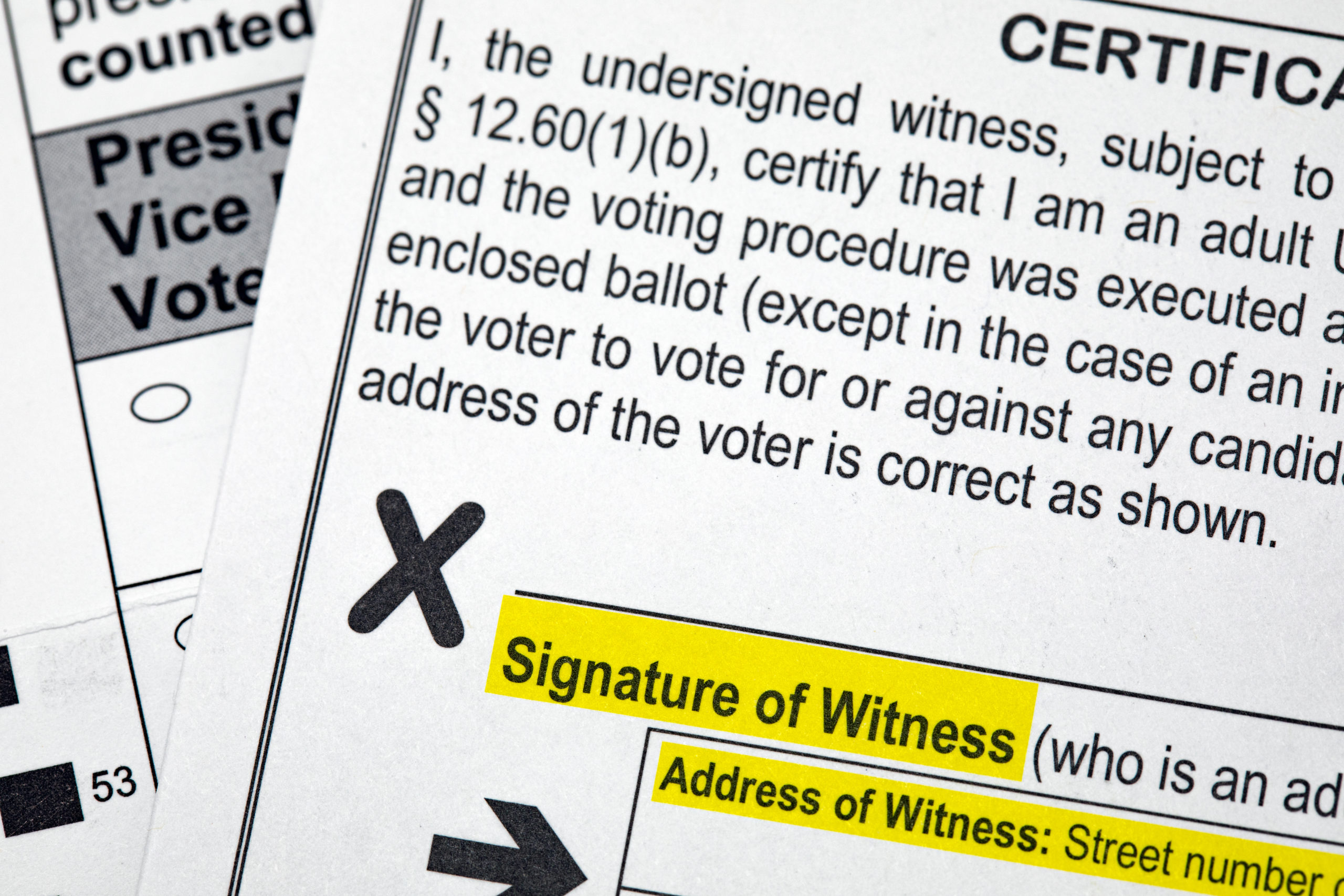

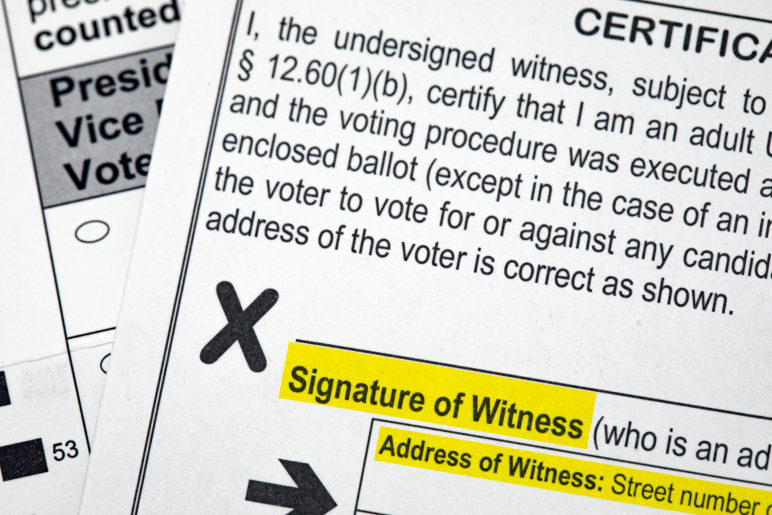

Ballot witness signatures: A toothless rule that hurt eligible voters

The requirement to have a witness sign one’s absentee ballot envelope is an unnecessary regulation that should raise hackles. Aversion to state overreach is quintessentially Alaskan, after all. If the witness rule actually made elections more secure, that would be one thing. But the signatures do not appear to protect against fraud and there is no process to check their legitimacy. Yet, in election after election, enforcement of what is essentially an empty gesture has disenfranchised hundreds of eligible absentee

Yet, in election after election, enforcement of what is essentially an empty gesture has disenfranchised hundreds of eligible absentee voters. Ballots with no witness signature get tossed out.

voters. Ballots with no witness signature get tossed out.

More than 450 of the record 62,455 Alaska voters who applied to vote absentee in the August 2020 primaries had their ballots rejected for lack of a witness signature. This is a pattern. Failure to fulfill the witness requirement was the top reason for rejected ballots in the last three Alaska primaries.

Nearly twice as many Alaskans requested absentee ballots for this November’s general election. If those voters are rejected at the same rate as in the primary, nearly 1,000 voters would fail to have their votes counted.

Advocates for voting rights urged Lieutenant Governor Kevin Meyer in a letter on August 31, to refrain from enforcing the requirement in the general election, but Meyer said he could not “unilaterally” do so, calling witness signatures “central to the absentee ballot statutory scheme.” Eventually, Meyer and Alaska’s Division of Elections would find themselves in court trying to make the case for why nearly 120,000 Alaskans should jump through a pointless (and possibly dangerous) hoop to vote absentee during a pandemic.

Voting access prevails in a late-breaking court fight

On September 8, the Arctic Village Council, the League of Women Voters of Alaska, and two private citizens filed a complaint in Anchorage Superior Court requesting that the state waive the witness requirement for the 2020 general election. The plaintiffs said the requirement violated Alaskans’ constitutional right to vote.*

Already in normal times, finding someone who is 18 years or older to watch you sign your ballot, and then add their own signature is inconvenient and unnecessary. But these are Coronatimes. Asking Alaskans at higher risk of suffering, if not dying, from the virus to seek out a witness to stand near them as they sign their ballot is an extra barrier to safely voting. The Trump administration’s surprise rule change disallowing US Postal Service workers from acting as witnesses made it even harder.

Plaintiffs also argued that the requirement disproportionately disadvantaged Alaska Natives in dozens of far-flung rural communities off the road system. Voters in remote villages are relying far more heavily than usual on mailed ballots this year, but for communities with strict shelter-in-place orders, the witness requirement is an additional barrier to voting. In Arctic Village, for example, residents may not gather with anyone anywhere outside their households. That means they can’t vote in person and would need to live with someone who’s old enough to be a witness to safely vote. For those who live alone, it’s an impossible bind.

The state of Alaska argued that the suit was filed too late. Early voting would be starting in just over a month. State officials said there would be no time to properly retrain its election workers and notify voters of the change. The courts were skeptical. After all, the state could easily tell election workers to count all absentee ballots with or without a witness signature, as long as they were properly submitted and signed. As for voters, the state could simply tell them to ignore the requirement.

The state also argued that the witness signature requirement is necessary to help prevent fraud. But it’s hard to see how. The state has no process to check the legitimacy of witness signatures. The Division of Elections’ requirement to provide identifying information, such as date of birth, on the absentee ballot envelope is a more effective check. When asked by Alaska Superior Court Judge Dani Crosby whether the witness requirement had ever played a role in detecting fraud, the state “could not identify any such instance in recent memory, and was not sure whether it had played a role in detection in the more distant past” according to court documents. Voter fraud is rare, but in an egregious case involving Alaska State Representative Gabrielle LeDoux, irregularities on absentee ballot applications (not witness signatures) were the key to alerting investigators that she may have been involved in a scheme to use the names of deceased voters on absentee ballots.

On October 5, Crosby ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, represented by the ACLU, Native American Rights Fund, and Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. “Application of the witness requirement during the pandemic impermissibly burdens the right to vote,” Crosby wrote. She called the state’s case “not sufficiently compelling.”

Not content with the decision, Lieutenant Governor Kevin Meyer, who oversees statewide elections, followed up the next day by seeking a review by the state Supreme Court. A week later, the higher court upheld the lower court’s decision.

Good vote-from-home elections don’t need witness requirements

Following the Supreme Court ruling, the state of Alaska began informing voters of the change on Twitter and Facebook, in direct mailings, and on the Division of Elections website. Now, absentee ballots without witness signatures will be counted in the general election, assuming voters fulfill all other requirements, such as signing and sealing the return envelope.

Oddly, the same administration that sallies forth to remove sensible environmental regulations for resource developers, vigorously defended a nonsensical one that would have affected tens of thousands of Alaska voters. Of the 11 states that normally require a witness signature, only five(Alabama, Louisiana, Wisconsin, South Carolina and North Carolina) are still enforcing the rule this year. Others, including Rhode Island and Minnesota, have dropped it.

The court-ordered waiver only applies to this election, but Alaska should consider making the change permanent. Of the five states that vote purely by mail—Colorado, Hawai’i, Oregon, Utah, and Washington—none have witness requirements. Neither do other states with high rates of voting by mail, such as Arizona, Montana, and Nevada. And neither does the municipality of Anchorage, which has conducted local elections completely by mail since 2018. Instead, these vote-from-home jurisdictions use verification of voter signatures to check voters’ identities and prevent fraud.

Witness signatures burden some voters yet have not played a role in ferreting out voter fraud in Alaska. To protect all Alaskans’ right to vote, the Legislature should permanently do away with the extraneous regulation at the earliest opportunity. In its place, lawmakers should require a robust signature verification and ballot cure process for absentee ballots. After all, voting should be as safe, convenient, and fair as possible.

*See Article 5, Section 1 of the Alaska Constitution

Sightline Institute is a 501(c)3 non-profit organization and does not support, endorse, or oppose any candidate or political party.

Jeannette Lee, senior researcher, focuses on democracy and housing issues from Sightline’s office in Anchorage, Alaska. Her work before coming to Sightline included serving as a consultant at the Adaptation Fund and United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, a federal natural gas researcher, and a journalist for The Associated Press in Alaska and Hawai`i and Atlantic Media Company in Washington, DC. Jeannette earned her BA in history from Yale University and her MA from the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, where she focused on energy and climate issues in the Arctic. Find her latest research here.

For press inquiries and interview requests, please contact Anna Fahey.