The Portland Charter Commission is wrestling with which election and governance systems will give Portlanders the best representation and accountability in City Hall. In the 20th century, several American cities tried a reform—proportional representation—that successfully fought corruption and broadened representation. They fought party corruption and elected women, people of color, and minor parties. But they became victims of their own success, facing backlash from party power players and from people who did not think that people of color and minor parties deserved a say in governing.

Portland could learn from both the successes and the repeals of proportional representation in other American cities. In the 1900s, those cities were not yet ready to give everyone a voice, so when they adopted a system that did just that, it was vulnerable to repeal. Is Portland ready to truly admit that everyone—including women, people of color, and those with minority views—deserves a voice in the city? If yes, this might be just the right time and place to implement a fair voting system and make it stick.

Timeline of American Proportional Representation

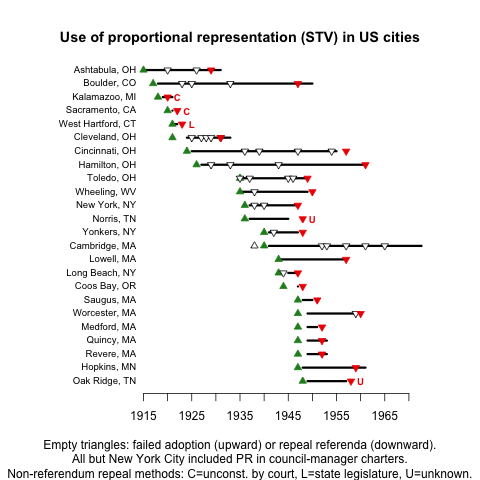

During the first half of the twentieth century, more than twenty cities across the United States implemented proportional representation to elect their city councils. The chart below describes the journey of proportional representation in various cities: green triangles represent adoption; white triangles catalog unsuccessful repeal efforts (and one unsuccessful adoption in Cambridge); and red triangles document successful repeal. Proportional representation was adopted in places as big as New York City (then population seven million) and as small as Coos Bay, Oregon (then population five thousand). Almost all of these cities repealed it within a few decades, except for Cambridge, Massachusetts, which has used it continually since 1941 to elect its 9-member City Council and 6-member School Committee—surviving at least five repeal efforts.

Ranked choice voting has seen a 21st-century resurgence in the United States, including the multi-winner form that produces proportional representation. Since the Millennium, proportional ranked choice voting, also known as single transferable voting, was adopted by Minneapolis, Minnesota, and Eastpointe, Michigan. It has been enacted for upcoming elections in Albany, California; Amherst, Massachusetts; and Palm Desert, California, in the next few years.

While all of these places have their own unique history with proportional voting, we’ll focus here on two cities that exemplify some patterns that appear time and time again: Cincinnati, Ohio, and New York, New York.

Cincinnati, Ohio

With no disrespect to the Queen City, Cincinnati is not on the tips of many Northwesterners’ tongues (1990s Mariners fans excluded). Back in the day, however, it was one of America’s 10 most populous cities from 1830 to 1900 and for many of those years outranked every other city outside the Eastern Seaboard except for New Orleans. The city was a hotbed of progressive activism and reform, and it was even called the “Paris of America” in the late 1800s amid the construction of immense architectural projects like the Cincinnati Music Hall.

Like many cities in the Eastern United States, local races were partisan through much of the 19th and 20th centuries. In the early 1900s, the city used a hybrid system to elect 32 councilors—26 ward representatives and six at-large seats. City hall was a Republican machine. Boss Cox (chair of the Hamilton County Republican Committee) and his successors doled out gifts of money, government jobs, and influence in exchange for support of their chosen candidates. In a 1911 public statement extoling his civic virtue and promising that he would not retire anytime soon, Cox himself stated that “The people do the voting. I simply see that the right candidates are elected.”

Gerrymandering made most wards safe for Republicans in the general election, so the Republican primary became the only chance at competition. But because primaries are low-turnout races, the party players only needed to influence about 15,000 votes to win each ward primary. From there, gerrymandered ward boundaries helped Republican nominees win 91 out of 96 seats elected in the three winner-take-all elections prior to 1925 (1913, 1917, and 1921). The 1921 election seated 31 Republicans and 1 Democrat to City Council, despite 44 percent of the electorate voting for Democrats.

It’s easy to see why Cincinnatians were ready for a fair voting system in 1925.

Cincinnatians organize in favor of reform

In response to the abuses of power and corruption of the one-party rule era, Cincinnatians in favor of good government established a civic group called the Charter Committee. Various reform attempts had started up and fizzled out in the Boss Cox era, but Charter would end up influencing city politics until the present day, acting as a sort of independent political party. Charter drew its initial members and support from several local civic groups and demographics, including:

- The Cincinnatus Association, a public affairs-minded group of business and professional leaders

- The Birdless Ballot League (referring to the Republican eagle and Democratic rooster symbols), which promoted nonpartisan ballots and nomination by petition as opposed to party primaries

- Local progressives associated with Bob LaFollette’s 1924 presidential campaign

- Unions and labor supporters

- Middle- and upper-class Black residents who had started to break with the Republican Party

- Republicans opposed to the current boss or in favor of more labor-favorable politics

- Democrats who were locked out of city politics by the Republican machine

These groups all united in the Charter Committee to push for a reform plan that included a nine-member City Council elected via proportional ranked voting and a hired city manager position. The last two groups listed above, reform Republicans and Democrats, had a lot to gain. The winner-take-all, ward-based elections of that era benefitted the political machine of mainstream Republicans. Reform Republicans and Democrats had public support from voters, but the system prevented them from translating support to seats on council. A proportional system that gave all voters more power would inevitably elect a greater diversity of voices, not just mainstream Republicans.

Voters choose Proportional Representation, and it works for three decades: 1925-1957

The election of November 1924 was a Presidential election with high turnout, and Cincinnati voters overwhelmingly—69 percent in favor—approved a ballot initiative to move to a proportional council with a city manager.

Cincinnatians found their proportionally-elected councilors both more competent at governance and more representative of diverse city populations than ward representatives in the preceding decades. Previous councils were full of saloon owners, prized for their ability to generate Republican votes on election day. But proportional voting made councilors more accountable to voters. Councilors did their jobs, and voters were happy—despite the low barrier to entry for new and politically extreme candidates, the proportional period in the city featured a remarkable lack of turnover or deadlock on city council.

With the proportional system, Cincinnati voters elected their first Black councilors. Though Black candidates had run in wards, none had ever won a seat. But proportional citywide voting consistently elected a Black candidate. Ten of the fifteen councils elected with proportional voting included at least one Black councilor.

Ted Berry

Ted Berry was an institution unto himself in Cincinnati even before his tenures on city council. He was the first Black valedictorian at any Cincinnati high school and won prizes in writing and speech. Berry worked at a Kentucky steel mill to pay tuition to the University of Cincinnati, then continued onto the university’s law school where he was the only Black student in his class. He went on to be a successful civil rights lawyer, becoming the first Black assistant prosecutor for Hamilton County. Berry would serve multiple terms as president for the local branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and later spend time on the organization’s national Board of Directors. Thurgood Marshall, who would later argue against “separate but equal” segregation in Brown v. Board and become the first Black Supreme Court Justice, was a close colleague of Berry’s. In 1945, Berry and Marshall led the legal defense for a group of Tuskegee Airmen who had been arrested and court-martialed for protesting segregation in facilities on an Air Force base in Indiana, a practice which was in violation of military regulations at the time but went on nonetheless.

Ted Berry won a seat in four straight proportional elections, from 1949 to 1957. He was endorsed by the Charter Committee, not just by the Democratic or Republican parties. Berry’s detractors engaged in a mudslinging campaign during his 1949 election. For example, Cincinnati Sheriff Julius Mund allegedly called Berry a Communist in a private meeting. Despite the smear campaign, Berry was elected to a council seat.

Berry went on to win the most votes for council in 1953 and 1955. Under the charter, city councilors picked from amongst themselves who would serve as the city’s (mostly ceremonial) mayor, usually choosing the councilor who had received the most first-choice votes in the last election. But when Berry, a Black man, won the most votes, the other councilors chose white councilors as mayor after the 1953 and 1955 elections.

White precincts lead the vote to repeal proportional voting

Ted Berry was poised to receive the most first-choice votes in 1957, once again raising the question of whether he should rightfully be the mayor of Cincinnati. Some white Cincinnatians decided they would rather repeal the system than have that happen. Rumors spread that Berry was buying a house in any or all of the majority-white neighborhoods in town, a uniquely political iteration of the blockbusting that real estate agents were instigating in white neighborhoods across the country. Backers of the repeal movement asked: “Do you want Ted Berry to be mayor of Cincinnati? Do you want Ted Berry for your next-door neighbor?” The New York Times reported on “an anti-Negro whispering campaign” that sought to prevent Ted Berry from becoming mayor, citing local observers that linked racial attitudes about the vote to white backlash against the integration of Little Rock’s Central High School.

The 1957 repeal campaign succeeded where four past repeal efforts, largely backed by the political parties, had failed. In a low-turnout, odd-year special election, 55 percent of voters voted to repeal proportional voting. Majority-white precincts voted for repeal by two-to-one margins, while majority-Black precincts voted four-to-one to keep the system.

Mainstream Republicans had always disliked proportional voting because it took away their outsized power on council. But in the 1940s, Democrats saw they might become a majority soon, based on growth in Democratic vote shares in urban areas nationwide, and they wanted to return to a system that would give an unfair advantage to the biggest party. They were right. In 1971, the city council would select only the second Democratic mayor Cincinnati had seen in nearly 60 years, and no Republican has led the city since then.

The 1957 repeal instead enacted a system of bloc voting locally referred to as “9X”, where voters can vote for up to 9 candidates and the top 9 vote-getters are elected to office. This system (also used in many Oregon cities) allows a well-organized majority to capture every seat on council, leaving minorities with no voice. In the November 1957 municipal election, held under the new 9X rules, lone Black councilor Ted Berry was the only incumbent Charter candidate to not gain re-election. Cincinnati still uses this system today. Although the city is 42 percent Black, only two of the city’s nine councilmembers are Black.

Courtesy Archives and Rare Books Library, University of Cincinnati

In 1988, voters in Cincinnati rejected a ballot initiative that would have reinstated proportional representation. Support followed similar precinct boundaries to racial divisions in the city, and one local political scientist estimated that 80 percent of Black voters supported proportional representation compared to only 33 percent of white voters. In 1992, fourteen Black Cincinnatians unsuccessfully sued the city under the Voting Rights Act of 1965, arguing that the 9X system was racially discriminatory in diluting Black voting power. Ted Berry testified in this trial that during the proportional era “the primary motivation for each effort to repeal [proportional representation] was… the desire and intent to dilute the impact of a mobilized, unified black vote.”

New York City

The Big Apple has been all over election news in the last few months, for both good reasons and bad. The Board of Elections committed unforced errors left and right in the city’s first election under new ranked choice voting (RCV) rules, but these issues are more in line with long-running deficiencies in the agency rather than any problem with the new voting system. And indeed, RCV functioned exactly as it was expected to! Coalitions formed, candidates sought second- and third-choice votes from their opponents’ supporters, and observers expect the incoming city council to be one of the most diverse in the body’s history.

This is not New York City’s first experience with fairer election methods. For a decade around World War II, the city was the largest of a handful across the country using proportional representation and ranked ballots. For a decade, voters got real choices about the candidates and policies they wanted to see on city council. Let’s dive into how this came to be and which groups joined forces to take it all away.

Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall was the Democratic political organization in Manhattan through much of the 19th and 20th centuries, and it was the country’s most well-known political machine. Under leaders like Boss Tweed, Tammany Hall regularly held an iron grip on city hall through bribery, kickbacks, patronage, and other corrupt practices. For the 15 years before proportional voting, Democrats held over 80 percent of seats on the city’s Board of Aldermen. In 1931, Democrats received 65 percent of the vote citywide but captured 64 of the 65 Board seats. Republicans only got one seat despite receiving 26 percent of the vote (worth 17 seats proportionately), and Socialists were locked out entirely with 8 percent of the vote (worth 6 seats proportionately).

Tides began to shift against Tammany in the 1930s. Then-Governor of New York Franklin Delano Roosevelt prompted a judicial investigation into the machine’s corruption, and proponents of proportional representation took advantage of this political moment. Fiorello La Guardia, a Republican mayor who took office in 1934 amid one of several waves of reform sentiment, established a commission that went on to recommend proportional representation to voters in 1936. City newspapers generally came out in favor of the reform, and labor representatives, women’s groups, and good government organizations all organized to support it. Third parties like the American Labor Party supported proportional representation as well, as it would give them the chance to win seats in accordance with their level of support from voters. In 1936, over 60 percent of New York voters supported proportional representation in a referendum.

The Proportional Representation Era: 1937-1947

New York’s system was a variant of multi-member districts: candidates would run for seats within each borough, and the number of seats given to each borough was determined after the votes were in, based on how many votes were cast in each borough. This mechanism avoided the constant underrepresentation and redistricting issues caused by rapid population shifts from Manhattan to the other boroughs.

Unlike in Cincinnati, the previously-ruling Democratic Party never lost their grip on a council majority. However, they were reduced to the modest majority that they actually warranted from popular vote instead of their overrepresentation from winner-take-all districts. And other parties got a meaningful voice on council. Proportionally-elected councilors were more competent and diverse than the preceding machine era, and Democrats often had to attract votes from the opposition in order to pass ordinances. Despite this larger opposition (or perhaps because of it), council passed more substantive legislation during the decade of proportional voting.

Under proportional voting, women, people of color, and minor parties got some of the representation that they were barred from under winner-take-all elections. The 1941 election was a watershed for this. Three women, a Black man, and a Communist were elected to council – the first in the body’s history.

The Red Scare, Major Party Fears, and Repeal

When Peter Vincent Cacchione, an Italian Communist from Brooklyn, and Ben Davis, a Black Communist with strong support in Harlem (the major Black neighborhood in Manhattan), won seats in 1941 and 1943 and again in 1945, proportional representation began to be tied to Communism, and media support for the system declined. Opponents complained that minority groups were being overrepresented. In fact, minority groups were perennially underrepresented under winner-take-all systems, and proportional voting suddenly allowed these groups to punch at their weight class.

Davis would be elected once more in 1947 before anti-Communist sentiment resulted in his arrest for alleged “subversive activities” under the Smith Act (which would soon be declared unconstitutional). He was one of ten Communist Party leaders tried and convicted for their political speech, contrary to First Amendment protections. Davis would serve three years in federal prison.

Proportional representation had survived repeal efforts in 1938 (via state constitutional convention) and 1940 (via local initiative), but the combined anti-Communist and anti-Black sentiment grew to be too much for it. Just like proportional voting advocates took advantage of public sentiment against the Democratic machine to institute the reform, its detractors took advantage of public sentiment against Communists and entrenched anti-Blackness to repeal it. Tammany Hall described proportional voting as a “Stalin Frankenstein” that allowed Communists to swindle good Americans. All five Democratic borough leaders came out forcefully against proportional representation, accompanied by their substantial war chests. White Republicans, worried that their domination in other winner-take-all cities would be threatened if proportional voting caught on, joined forces with Democrats in the repeal effort, invoking racial resentment. By contrast, Harlem Republicans stated:

“Political leaders say their aim is to keep Ben Davis and the Communists out of the city council. We think the effect [of repealing proportional representation] will be to keep Ben Davis and all other Negroes out of the City Council.”

The numerous minor parties that benefitted from the system stayed firm in their support of it, but that wasn’t enough to overcome the unified attack by the two major parties. In November 1947, Tammany Hall successfully led a repeal of the proportional representation system adopted 12 years earlier. New York City went back to a district system that gave Democrats an outsize advantage: they won 21 of 25 Council seats, Republicans took the other four, and other parties were left with no seats at all despite collecting more than a quarter of the vote citywide. One disingenuous slogan adopted by the repeal crowd was “P.R. means People’s Rule.” Imagine that!

In modern days, Democratic candidates are a shoo-in for most elected offices, and the Democratic primary is where the real decisions get made about who will lead the city – leaving Republicans to play second fiddle and other parties out in the cold.

What Does This All Mean for Portland?

When it comes to giving minority groups a voice on city council, proportional representation works. In Cincinnati and New York City, the minority groups in need of a voice were Black people, women, and minor parties such as Labor, Communist, and Charter. In Portland, groups in need of a voice include people of color, renters, small business owners, cyclists, and bus riders. And although Portland races are nonpartisan, there may be interest groups—such as Portlanders who prioritize acting on climate change, environmental justice, or working families’ interests — that deserve more play in city hall, based on how many voters prioritize those issues.

Though the rise and fall of proportional representation in Cincinnati and New York had a lot to do with party politics, proportional representation works for nonpartisan elections. The specific kind of proportional representation used in many American cities is a multi-winner form of ranked choice voting, sometimes called single transferable voting. Unlike party-based proportional systems widely used in Europe and South America, this form asks voters to rank candidates directly, without a need for parties to mediate. Parties can still endorse candidates for office, as they already do in local elections (even nominally nonpartisan ones), but voters have the power to directly choose candidates. This voter-centric model is also used for national elections in Australia and in Ireland.

In the 20th century, Cincinnati and New York proved not yet ready to give minorities a voice on city council. But they also proved that proportional representation can do just that. Maybe now, in the 21st century, Portland is ready to embrace the voices of all Portlanders, not just those in the majority. If that moment has come, Portland can adopt proportional voting to make it happen.