In 2019 Wayne Thorley, then Nevada’s Deputy Secretary of State for Elections, promised a state legislative committee that Nevada taxpayers could “save a lot of money.” The trick, Thorley said, was to pass a low-profile bill to reschedule local elections so that they would be on the same ballots as federal ones. Millions of dollars of savings, he claimed, were there for the taking through election consolidation.

Thorley’s argument was not unusual. Cost savings are a routine refrain in legislative discussions of consolidation. I have heard them invoked repeatedly, like a mantra, in election rescheduling hearings in Arizona, California, Montana, Nevada, and Washington. Over and over, from the left and the right, proponents point out that synchronizing elections not only commands overwhelming popular support, boosts turnout, improves government accountability, and brings out a more representative electorate but also saves money.

How much money, though? Thorley didn’t say, and few others have offered estimates.

The potential economies are large, no doubt. The cost of running local elections at off-cycle times (that is, at times other than Election Day in November of even-numbered years) runs to tens of millions of dollars a year in Cascadia. In the United States, it amounts to perhaps $2–$5 billion per year nationwide.

An elections-cost calculation usable for any city or state

As far as I can tell, though, no one has ever conducted a meticulous, CPA-proof before-and-after study on how much money election consolidation would save. And no one has documented the change in spending in cities that have moved their local elections to align with federal ones.

That is surprising, given the near-violent controversy over the fairness and security of voting systems in the United States. You might assume that every aspect of the country’s elections would have been audited in excruciating detail. Instead, the question of voting schedules is a weird, neglected backwater of election debate and its costs little attended.

Election budgets are buried in larger budgets for county clerks or auditors and for various city or state bureaus, and they are rarely analyzed separately. These budgets are also dwarfed by other spending categories and therefore draw little scrutiny. Charles Steward III, a political scientist at MIT, wrote, “The estimated cost of conducting elections on an annual basis is roughly what local governments spend managing public parking facilities.”

In other words, it’s crumbs.

In this article, I offer a back-of-the-digital-envelope estimate for three Cascadian states that hold off-cycle elections and their main cities. The analysis method I use is admittedly crude; I based it on all the data points I could assemble, though I could not find many data points. However, the method allows anyone anywhere to estimate potential savings for their own off-cycle city or state elections, and it’s simple and transparent enough to allow for quick upgrades as data improve.

Examples of elections-cost savings from Idaho, Montana, and Washington

Sightline estimates potential savings in Idaho, Montana, and Washington, the three Cascadian states that could easily move their municipal elections to Election Day, to be more than $30 million per two-year election cycle.

The method used to determine these savings, detailed in the appendix, is simple and built from real-world examples. First, I estimated the range of total Cascadian spending for off-cycle elections based on expenditure data from two local examples: King County, Washington, and Anchorage, Alaska. Second, I estimated potential savings from two other local examples: a set of on-cycle and off-cycle elections in Nevada cities and a before-and-after estimate from the city of Concord, California. And third, I reality- checked each of these examples against other data points I could find.

From these examples, I created a two-by-two matrix: high cost and low cost, and high savings and low savings. The matrix yielded four scenarios that ranged from savings of under $18 million to almost $47 million. These estimates included each municipality (incorporated city or town) in these states. In the case of Seattle, for example, projected savings amount to $3.2 million per biennium (see Table 1). Savings in Boise, Idaho, are estimated at $1.1 million every two years.

The savings for any jurisdiction not listed can be estimated using the methods described below. At its simplest form, the method suggests multiplying the US Census Bureau’s estimate of citizens of voting age for any municipality by an average savings of $5.92 per biennium to estimate savings from election consolidation.

Table 1. Idaho, Montana, and Washington could save millions of dollars by moving municipal elections to federal Election Day.

Estimated potential savings from election consolidation in Cascadian off-cycle states and their cities with a population of ≥ 100,000, per two-year election cycle

| (millions) | |

|---|---|

| Idaho (all municipalities) | $5.4 |

| Boise | $1.1 |

| Meridian | $0.5 |

| Montana (all municipalities) | $4.4 |

| Billings | $0.5 |

| Washington (all municipalities) | $20.6 |

| Seattle | $3.2 |

| Spokane | $1.0 |

| Tacoma | $1.0 |

| Vancouver | $0.8 |

| Bellevue | $0.5 |

| Kent | $0.5 |

| Everett | $0.5 |

| Renton | $0.4 |

| Spokane Valley | $0.5 |

| Total | $30.5 |

Source: See appendix.

States would save “a lot” from consolidating elections

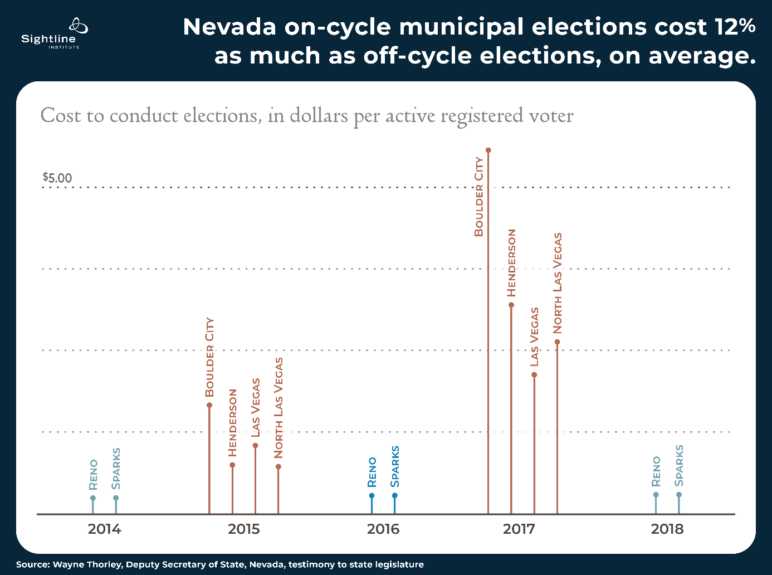

These estimates stem from a small set of real-world examples. Thorley was not exaggerating when he quantified savings as “a lot.” The budget figures he presented, displayed in the chart below, show an average savings of 88 percent per active registered voter. If anything, these figures underestimate the gap between on-cycle and off-cycle expenses in Nevada because they do not include election department staff time in the off-cycle cities. Thorley’s data, covering 2014–2018 for cities in Nevada’s two most populous counties, illustrate the pattern evident in other comparisons among jurisdictions.

For example, a 2013 Greenlining Institute study of six California cities (half of them on-cycle and half off) found that on-cycle elections cost 92 percent less per ballot cast. In 2015 legislative analysts in Sacramento noted that San Diego’s 2012 on-cycle election cost that city only 1 percent as much per voter as Los Angeles spent on its 2011 off-cycle election. With ratios like these, even with vastly higher turnout in on-cycle elections, total expenses would still shrink markedly. The city of Concord, California, for example, projected an overall savings of 57 percent from switching to on-cycle elections.

For example, a 2013 Greenlining Institute study of six California cities (half of them on-cycle and half off) found that on-cycle elections cost 92 percent less per ballot cast. In 2015 legislative analysts in Sacramento noted that San Diego’s 2012 on-cycle election cost that city only 1 percent as much per voter as Los Angeles spent on its 2011 off-cycle election. With ratios like these, even with vastly higher turnout in on-cycle elections, total expenses would still shrink markedly. The city of Concord, California, for example, projected an overall savings of 57 percent from switching to on-cycle elections.

In Arizona, even small cities that switched to on-cycle elections have reportedly been saving hundreds of thousands of dollars per election. And in big cities, the savings may even be in the millions. Joe Gloria, CEO for Operations at the National Association of Election Officials and former Clark County (Nevada) registrar of voters estimated that the savings in Las Vegas and the four other cities in Clark County exceeded $5 million per election cycle after the change to on-cycle elections. And in 2022 San Francisco’s comptroller estimated the savings from shifting five city executive elections to on-cycle at almost $7 million every two years.

Local officials can sharpen the estimates from this initial calculation

These figures are not definitive because actual savings depend on the particulars of each case. Balloting methods and costs vary widely, and big savings only come when a jurisdiction can cancel entire elections. Shifting the mayor’s race to the main Election Day but leaving other local elections such as those for school board on the old schedule, for example, might preclude savings. What’s more, the method estimates total savings but does not indicate to whom the savings will accrue since the division of expenses among localities, counties, and state governments varies by state and county.

For the purposes of this exercise, I assume that election consolidation means moving all local elections on-cycle and canceling the off-cycle local election dates. Beyond that, though, administrative details matter, such as:

- How many local elections a jurisdiction has per biennium;

- Whether all off-cycle races and questions fit on the ballots that would have already been printed;

- Whether nonpartisan local races need different ballots in primary elections, as do partisan state and federal races; and

- How much extra work is required to customize ballots for different jurisdictions. (Election administrators often generate dozens of ballot variations to reflect the different offices and questions before voters in different precincts.)

To improve these estimates, budget writers for each county’s election administrator could scrutinize their expenses line by line, separating fixed costs from incremental ones and developing precise numbers to specify election consolidation’s potential costs and benefits. What’s more, before-and-after analyses from cities that have already consolidated their elections would give us a much clearer picture of these impacts.

In the interim, these estimates provide a starting place for grasping the scale of potential savings from election consolidation. It appears to be large (on the order of $30 million of savings every two years in just three states) and would do something that voters want anyway.

Appendix: Methods

Estimating the savings from election consolidation is challenging. I found no peer-reviewed studies that examined the question and surprisingly few analytic reports from any source. Election agency budgets are not usually broken out per election, and many election agency budgets are lumped in with the larger budgets of the county clerk offices where they reside. When jurisdictions calculate state costs per election, they do not often share their definitions or methods, making numbers difficult to compare. Few jurisdictions that estimate costs per election make clear whether the estimates cover only that jurisdiction’s own costs or whether they include other jurisdictions’ costs. In California, for example, cities are typically required to pay all the costs of off-cycle elections but only a few of the costs of on-cycle elections, which counties usually pay. Consequently, cost savings to cities may partly be offset by cost increases to counties. I have seen estimates of costs per ballot cast in off-cycle elections vary from pennies to more than $50. Costs do vary, of course, but in the absence of a uniform set of accounting practices, it’s hard to say anything about these values with confidence.

In this method, I estimated Cascadian spending for off-cycle elections from two local examples. Then I estimated savings from two other examples. Finally, I reality-checked these examples against other data points.

In all estimates, I ignored British Columbia, the Canadian part of Cascadia. The province cannot realistically synchronize local elections with provincial or federal elections because those elections are not scheduled in advance but can be initiated by the provincial or federal government on short notice. Municipalities therefore cannot consolidate their elections.

I also omitted the Cascadian state of Oregon and the states of California and Wyoming, which are partially in Cascadia, because they conduct all or almost all their municipal elections on the national cycle. I discuss Alaska but did not include it in the summary table because its three-year municipal terms of office make consolidation a much more difficult policy change, while elsewhere consolidation is just a matter of changing an election schedule.

I focused on Idaho, Montana, and Washington because they currently require municipalities to vote in November of odd-numbered years and they all considered legislation in 2023 to allow or require election consolidation. That said, the method of estimating used here could be applied to any state or city in which municipal elections are off cycle.

Calculating total cost of off-cycle elections

To estimate the range of total spending for off-cycle elections, I used two cases.

Case 1: High cost (King County, Washington)

King County, Washington, is Cascadia’s most populous county, with more than 2 million residents, 39 municipalities, and dozens of school districts and other local election jurisdictions. King County Elections is a leader in elections administration and known for its technical sophistication and reliability. It also conducts many elections because Washington gives localities four opportunities to hold elections in most years and five in presidential-election years.

King County Elections estimates the average total cost of off-cycle elections, including February and April elections in even and odd years, plus odd-year primary and generals elections, at $15.3 million per two-year cycle, based on a decade of data. In 2021 King County had a citizen voting age population of a little more than 1.5 million, according to the most current data from the US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS) five-year estimates. Per citizen of voting age, therefore, King County will pay $9.98 for multiple off-cycle elections in a two-year period. This estimate more likely understates than overstates current costs because it averages ten years of expenses, without regard to inflation or the county’s rapidly growing population.

In my estimates I rely on citizens of voting age rather than registered voters or ballots cast because the US Census Bureau regularly generates estimates for citizens of voting age in most US jurisdictions, and this figure is not influenced by the many exogenous factors that affect voter registration and turnout. By calculating off-cycle election costs and potential savings from consolidation as a value per citizen of voting age, I came to a method for generating at least rough estimates for any US municipality (or state) with off-cycle elections.

The King County estimate of $9.98 per voting age citizen is consistent with cost estimates from elsewhere and may be conservative. It’s lower, for example, than the cost of Georgia’s 2022 US Senate runoff, which was an estimated $75 million, or almost $10 per citizen of voting age in the state. (Keep in mind that this figure is for the runoff only, not the primary election or other off-cycle elections during a two-year cycle.) Similarly, in 2022, the elections budget in Missoula County, Montana, was $12.78 per citizen of voting age. New York City’s budget for its 2021 off-cycle municipal election worked out to $10.48 per citizen of voting age.

Idaho, Montana, and Washington’s combined population of voting-age citizens who reside in municipalities, according to the ACS, is 4.9 million. Assuming that King County’s election costs are typical, off-cycle municipal election costs per two-year period in these states is $48.6 million.

Case 2: Low Cost (Anchorage)

Most US elections are conducted by county governments, and those governments do not (and, in some ways, cannot) disentangle the costs of conducting off-cycle elections from on-cycle ones. Some costs are fixed, such as salaries and benefits for the core staff of these agencies, who are always managing operations, planning for security and upgrades, maintaining voter rolls, buying and repairing voting machines and ballot tabulators, recruiting and training poll workers, collaborating with elected leaders on policy questions, and otherwise keeping the elections infrastructure in working order. Counties typically conduct at least two elections a year and sometimes even four or five, such as primary and general elections, runoffs, special elections, and low-profile bond measures and levies. How to allocate overhead costs among these various elections is ultimately a matter of accounting conventions and judgment calls.

But Alaska is different, and that difference opens a window into the cost of freestanding municipal elections. In Alaska, the state government itself conducts state and federal elections, while city governments conduct local elections.1 These elections never happen at the same time, and they are conducted by different agencies with different staff members, equipment, and protocols.

The city of Anchorage’s elections budget shows what it costs to run independent local elections. Since 2014 Anchorage has spent about $600,000 on each of its main municipal elections, which are in April. That’s $2.84 for each citizen of voting age. Anchorage has spent additional amounts for various runoffs and special elections over the years, bringing the average annual total costs to $670,000, or $3.17 per year for each citizen of voting age. To make this estimate comparable to the King County biennial estimate, I doubled it to $6.34 because Anchorage conducts elections every year, none of which are on cycle. Extrapolating from Anchorage’s figure to all municipalities in the three off-cycle Cascadian states, the total two-year cost of off-cycle elections is close to $31 million.

A reality check for this figure of $6.34 comes from Minneapolis, Minnesota, where an analysis of election consolidation estimated a savings of $1.4 million in 2017, which works out to $4.70 per citizen of voting age that year. (That’s less than the Anchorage estimate but not wildly divergent.) Another reality check depends on the cost per ballot cast, a different measure of election cost. In Anchorage, the average cost per ballot cast was $9.79 for the city’s regular municipal elections between 2014 and 2021. This figure is in the same range as other estimates of cost per ballot cast in elections. For example, nonprofit organizations FairVote and Third Way surveyed election administrators in Texas and Louisiana about the costs of primary and runoff elections in 2018 and 2020 and found an average cost of $7 per ballot cast.

Calculating potential savings

To get from these estimates of the total costs of off-cycle elections to estimates of potential savings from consolidating local elections, I considered two cases: low savings and high savings. For low savings, I relied on the 57 percent savings projected in Concord, California. For high savings, I relied on Nevada’s 88 percent savings rate by comparing election costs in on-cycle and off-cycle counties. (As a conservatism, I disregarded Greenlining Institute’s 92 percent savings and San Diego’s 99 percent savings.) One weakness with these cases is that neither estimate makes clear whether its scope encompasses election costs for all levels of government or only those of municipal governments. If these estimates cover municipal but not county budgets, for example, they may overstate potential savings. Conversely, the Nevada data may understate the savings. In his presentation, Thorley noted that the data exclude the cost of county staff time devoted to off-cycle elections; including those costs would increase the savings to more than 88 percent.

Table 2 shows a two-by-two matrix of these cases and displays estimated savings per citizen of voting age, per two-year election cycle, which average to $5.92. Multiplying these products by municipalities’ citizen voting age population yields a rough estimate of savings under the four scenarios and under their average (see Table 3).

Table 2. Sightline’s preliminary method finds that election consolidation could save $3.61 to $8.78 per citizen of voting age, per biennium.

| Low cost of $6.34/voting-age citizen (Anchorage) | High cost of $9.98/voting-age citizen (King County) | |

|---|---|---|

| Low savings of 57% (Concord, CA) | $3.61 | $5.69 |

| High savings of 88% (Nevada) | $5.58 | $8.78 |

As a reality check for these estimates, I used the City of San Francisco comptroller’s 2022 estimate that local election consolidation there would save $6.9 million per biennium. This estimate comes to savings of $10.73 per citizen of voting ages, which makes my estimates seem conservative. Similarly, as noted above, Gloria, as former registrar of voters for Clark County, Nevada, estimated the financial savings of on-cycle election in his county at more than $5 million per year, with the savings per citizen of voting age landing at about the bottom end of the range in this matrix.

For the three Cascadian off-cycle states, I calculated potential savings ranging from under $18 million (for the low-savings, low-cost scenario—Concord savings and Anchorage costs) to nearly $47 million (for the high-savings, high-cost scenario—Nevada savings and King County costs). The average savings is more than $30 million.

Table 3: Potential Savings from Election Consolidation, in Cascadian off-cycle states and their cities of 100,000 people or more, per two-year election cycle

| Low Cost (Anchorage) | High Cost (King County) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place | High savings (Nevada) | Low savings (Concord, CA) | High savings (Nevada) | Low savings (Concord, CA) | Average |

(millions of dollars) |

|||||

| Idaho (all municipalities) | 5.1 | 3.3 | 8.1 | 5.2 | 5.4 |

| Boise | 1.0 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 1.1 |

| Meridian | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Montana,(all municipalities) | 2.6 | 1.7 | 8.1 | 5.2 | 4.4 |

| Billings | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Washington (all municipalities) | 19.5 | 12.6 | 30.6 | 19.8 | 20.6 |

| Seattle | 3.1 | 2.0 | 4.8 | 3.1 | 3.2 |

| Spokane | 1.0 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Tacoma | 0.9 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| Vancouver | 0.8 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Bellevue | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Kent | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Everett | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Renton | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Spokane Valley | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Total | 27.2 | 17.6 | 46.8 | 30.3 | 30.5 |

Thanks to Sightline researcher Todd Newman and to professors Zoltan Hajnal (University of California, San Diego), David Kimball (University of Missouri–St. Louis), and Zach Mohr (University of Kansas) for their review comments on an earlier draft of this article.