While other Cascadian jurisdictions have been struggling to adopt piecemeal housing reforms—reducing parking requirements in Washington, or legalizing duplexes in Oregon, duplexes and lot splits in California, and fourplexes in Portland—British Columbia just enacted all of this and more, in a single month: November 2023.

By legalizing apartment buildings up to 20 stories next to all Skytrain stations, legalizing fourplexes province-wide, eliminating parking requirements near transit, and proposing single-stair apartments, British Columbia has set a new standard for zoning reform in North America. More locally, it has created a framework for the construction of some of Canada’s best neighborhoods in the near future.

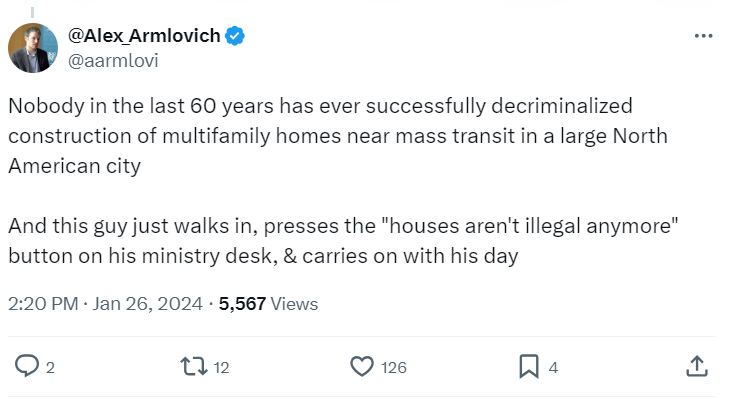

As Alex Armlovich, housing analyst at the Niskanen Center, recently tweeted about BC housing minister Ravi Kahlon:

Screenshot of X post from Niskanen Center senior housing analyst Alex Armlovich: “Nobody in the last 60 years has ever successfully decriminalized construction of multifamily homes near mass transit in a large North American city. And this guy just walks in, presses the “houses aren’t illegal anymore” button on his ministry desk, & carries on with his day”

The legalization of apartments in BC happened gradually, and then suddenly

For years, the opponents of transit and infill housing in British Columbia mostly had their way. Some development was allowed on old industrial sites, but a formidable dam of zoning regulations held back new homes and transit. Zoning rules preserved the built form of single-detached house neighborhoods, even as prices rose, making homeowners millionaires many times over.

The system may have reached its apogee in the year 2000 when Kerrisdale resident Pamela Sauder uttered her now-infamous opposition to a transit line: “We are dentists, doctors, lawyers, professionals, CEOs of companies,” she said, explaining why the area was unsuited to public transportation. “We are the crème de la crème in Vancouver.” Sauder and her fellow opponents of the proposed “Arbutus Line” won that fight, and the city routed both the transit line and accompanying new homes well to the east of Kerrisdale, along Cambie Street. The dam held.

In 2017, in the same style, media executive David Radler wrote in opposition to a seniors’ home proposed for Vancouver’s wealthy Southlands neighborhood. Radler wrote that Council “would be allowing one of the last upper-scale residential areas of the city close to the airport to be commercialized” if it approved the rezoning, harming the economy by ruining an area of “executive housing.” Despite this, Council approved the senior center, and construction is almost finished. A leak in the dam, perhaps. And the economy? Arguably not ruined by this one seniors’ home.

“You’re dropping the ghetto in Kitsilano…we are one of the treasures of the city.” This was the reaction of Kitsilano homeowner Judy Osburn to a proposed five-story apartment building in 2019. After 25 hours of heated debate over three days, Vancouver’s City Council voted eight to three to approve the building. An apartment building was allowed on a quiet, low-density street on Vancouver’s west side. The leak had become a trickle.

Four years later, in November 2023, the dam finally burst.

Under the leadership of Premier David Eby, Housing Minister Ravi Kahlon introduced and the Legislature passed Bills 44, 46, and 47, remaking British Columbia’s housing landscape. “The housing system as we have it now is not working,” Minister Kahlon told The Tyee.

To remedy this, BC’s government has enacted a wealth of reforms for residents to unlock much-needed new homes, in all shapes and sizes, across robustly transit-connected neighborhoods:

- Legalizing 4–20-story buildings near bus, rail, and subway stops

- Eliminating public hearings for proposed buildings that comply with local regulations and plans

- Ending parking requirements for housing in transit-oriented areas

- Allowing 4–6 homes on most lots and

- Considering the legalization of low-rise apartment buildings with a single staircase, instead of two.

The first of three important bills was introduced on November 1, 2023. By November 30, all three bills had been through first, second, and third reading, committee, and had been given royal assent. Both supporters and opponents of these changes have said the government is “ramming” these changes through, though they disagree on whether this is a good or a bad thing. For supporters of these changes, housing delayed is housing denied, and the speed of the reforms has been welcome.

This is in addition to moves earlier in the year to establish housing targets for municipalities with sticks and carrots to ensure that these targets are met.

With these reforms, BC’s government has shown just how much can be done quickly by a government taking the housing crisis seriously—at least, it shows what leaders who are committed to abundant housing can do when they operate in a unicameral parliamentary system of government with strict party discipline. Together, these changes set a new record for rapid legalization of apartments and multiplexes in North America.

Bill 47: Legalizing robust transit-oriented development

Governments looking to spur housing construction have many options. Among the fastest is to simply and directly legalize multi-story apartments. Traditionally delegated to municipalities, land use zoning remains within the jurisdiction of state and provincial governments in Canada and the United States; they have authority to step in and create their own zoning where municipalities have been unduly restrictive or exclusionary.

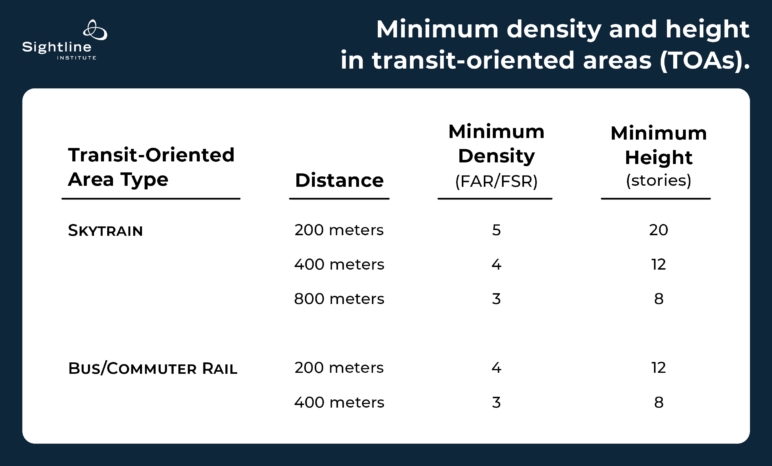

Recognizing this legal fact, British Columbia has just legalized up to 20-story buildings within 200 meters of all SkyTrain stops, 12 stories within 400 meters, and 8 stories within 800 meters. In addition, 8–12 stories are now legal next to many bus exchanges, and next to West Coast Express commuter rail stations, in all of the central municipalities of the Greater Vancouver region. Lower minimum densities and heights are also set for major bus exchanges in cities farther from Vancouver and outside the Lower Mainland.

The result is that a significant portion of Vancouver, and parts of surrounding municipalities with SkyTrain, now permit mid-rise apartment buildings.

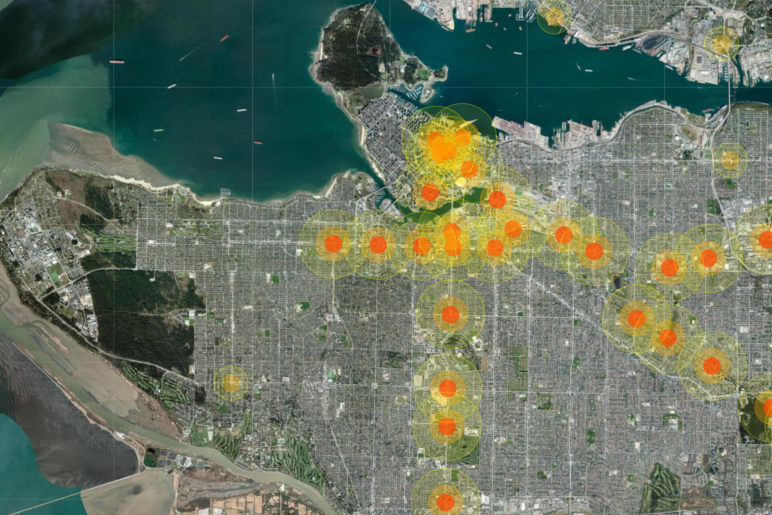

Figure 1: SkyTrain, bus, and commuter rail stations in Vancouver, with 200-, 400-, and 800-meter radii. Courtesy of Joss Messmer, used with permission.

These changes are part of Bill 47, which authorizes the Minister of Housing to designate transit-oriented areas (TOAs) and bus stations, setting both minimum densities and heights, as well as the distance from each class of TOA or bus station where they will apply. The Minister can also list new TOAs or bus stations by regulation, making it relatively easy to add new areas as SkyTrain expands, bus service increases, or future governments decide to upzone new areas with already-excellent bus service.

Bill 47 requires local governments to designate TOAs under their own bylaws, but it provides that the Province can step in and directly zone for apartments if the minister concludes that the local government is stonewalling.

Bill 47 also prevents cities from requiring off-street parking as part of housing projects in TOAs, except for accessible parking spots for people with disabilities. This moves away from the current system, in which cites arbitrarily decide how much parking each housing development requires and force developers to build that parking, whether residents want it or not. At $80,000 per underground space, these requirements can easily kill homes. It leads to the overbuilding of parking, too. A 2017 City of Vancouver study found that there were 1.5 residential parking spaces for every car in the dense West End neighbourhood—an oversupply of 8,000 parking spaces. Besides just the cost, building parking can slow construction, requiring huge and time-consuming parking craters before above-ground construction can begin. This is why the Squamish Nation’s Senawk project will have 6,000 homes with just 886 parking spots (it will have over 4,000 bike parking spots). BC Premier David Eby dismissed concerns about parking at Senawk as “NIMBY nonsense that I just don’t have a lot of time for because we’re in the middle of a housing crisis.”

Opposition political parties have leveled a variety of criticisms at the bill. While supporting transit-oriented communities in principle, one legislator said that the bill will lead to confusion and that some fire truck ladders are only equipped to go up to four stories.

Another common opposition claim is that new housing is racing ahead of available space in local hospitals and schools, to which the answer is, now and always: creating a housing shortage on top of a school or hospital shortage will not make things better. If we need schools for our children, then we should build those. And since we need housing, we should also build that. To the extent that new housing does increase population in a given area, it also brings in the property and income tax revenue that pays for new schools and hospitals.

The opposition BC Greens have also vocally objected to Bill 47 on the grounds that much of the new, dense housing may not have any affordability requirements. (Notably, the same criticism is rarely levied against more expensive, existing, lower-density housing.) But in most cases, that new, dense housing will be more affordable than the single-detached homes that they replace.

A more cutting critique of Bill 47 is its limited scope—in particular, its exemption, for now, of the south and west parts of the City of Vancouver, the areas of “executive housing” for the “crème de la crème” that have so long resisted apartments and transit. The entire area of Vancouver west of Arbutus has only one small, TOA-designated bus station. Future governments could (and should) remedy this limitation either by subway expansion on Vancouver’s west side or by designating more bus stations as TOAs—or better yet, both.

Multiplex policy success to depend on FAR and accountability measures

British Columbia’s government also passed legislation requiring municipalities over 5,000 people to legalize more small, multifamily housing across the province. With this, British Columbia followed Oregon, which legalized duplexes in cities over 10,000 people, plus triplexes and quadplexes in some areas; California, which legalized duplexes; and a variety of other jurisdictions. But the province went much further, legalizing four units on almost every lot, and six units on all but the smallest lots (more than 281 square meters), or near prescribed bus exchanges.

A binding provincial policy manual correctly sets out the problem this policy addresses, that of single-detached zoning that bans other housing types from even being options for people:

Single-family detached homes are out of reach for many people in a growing number of BC communities. However, zoning regulations that exclusively permit single-family detached homes often cover 70-85% of the privately held residential land base in communities.

One analysis found that these changes could produce 216,000–293,000 additional completed homes over 10 years, across the whole province.

In my last article, I argued that not just home counts, but also floor area ratio (FAR, the ratio of built floor space to lot size) was vital to small-lot zoning reform and that Vancouver should aim for a FAR standard of at least 2.0 to facilitate broad-based adoption of these zoning reforms. A FAR of 2.0 means that there is twice as much floor space in the building as there is lot area, so that a four-story building that takes up half of the lot would have a FAR of 2.0. Insufficient FAR standards can lead to marginal uptake that renders well-publicized zoning reforms merely symbolic. This happened recently in Toronto and in Victoria, BC.

One provincial report suggests that the FAR for missing middle will be set at just 1.5. While this may satisfy demand in lower-cost parts of the province, it will be of limited use in the extremely high-demand parts of Vancouver.

This policy also has a loophole that could be exploited by crafty municipalities seeking to maintain exclusionary zoning. Because the missing middle reforms only apply to detached and duplex zones, municipalities could enact their own fourplex zones at lower FARs. This would exempt them from provincial minimums while still falling below the provincial standards. Vancouver’s multiplex plan, for example, sets density at 1.0 FAR, just above the 0.86 FAR in detached home areas. City staff estimated this will spur 150–200 projects each year—a nice addition, but well short of the supply boost the city needs. To have the province’s largest city side-step the missing middle upzoning in this way would sent the wrong message. The province has tools to ensure compliance with both the letter and the spirit of its missing middle reforms, including further legislative amendments, and only time will tell the results of this showdown.

The success of these missing middle reforms will depend on both the FAR set by the province to support the minimum units, and on the province’s ability and willingness to prevent municipalities such as Vancouver from sandbagging progress by adopting subpar quadplex reforms—reforms that will not unlock construction of new homes on a scale commensurate with the shortage.

Considering single-stair apartment buildings

Along with these changes, and in response to a 2021 report for the City of Vancouver by Seattle architect Mike Eliason, British Columbia also announced that it will consider removing an unexpectedly important impediment to building more, and better, housing: the requirement that apartments between two and eight stories have two staircases.

This double-stair requirement is ostensibly a fire safety measure, though its effectiveness as such is questionable. What is unquestionable is that the double-stair rule severely constrains the number of city lots on which apartment buildings will fit. It also disqualifies whole categories of floorplans for the apartments in those buildings.

Single-stair apartment buildings, which are ubiquitous in Europe and parts of Asia, can have smaller floor plates and lower construction costs than double-stair buildings. Because they fit on most individual lots, their developers can skip the time-consuming and therefore expensive process of assembling multiple neighboring lots for each apartment block. Double-stair buildings usually need an elongated rectangular floor plate with a corridor connecting the stairs at each end. The corridor entails that most apartments have windows on only one face.

Single-stair buildings, in contrast, are usually erected around a central stair and have smaller floor plates. Most of their apartments are corner units, with windows on two faces, and in some designs, apartments span the depth of the building and have windows in three directions. Because both building codes and most humans prefer rooms with windows, single-stair buildings therefore make it easier to design larger apartments. (Vancouver-based documentarian Uytae Lee makes the case for single-stair buildings in a recent 12-minute video. Highly recommended!)

All hail North America’s new zoning-reform leader

After decades of damming the flow of apartments, transit, and renters, the regulatory walls of exclusionary zoning in British Columbia came tumbling down on November 30, 2023, when the BC Legislature passed Bills 44, 46, and 47. These measures put BC squarely in the lead of North American zoning reform.

This shift was made possible by a striking realization on the part of the provincial government: housing is extremely popular. For example, a recent poll found that two-thirds of Vancouverites support a First Nations-led project to build towers for 24,000 people on the Jericho Lands on Vancouver’s pricey and sparsely populated west side.

Housing is popular not just in Vancouver, nor just in Canada. A recent Pew poll found that 8 in 10 Americans support allowing apartments near train stations and job centers.

Not everyone is on board with these changes, of course. Some former mayors and councilors complain that these new policies show “insufficient regard for the responsibilities of local and regional governments for community planning.” (Considering the advanced state of British Columbia’s housing shortage, perhaps excessive regard for local and regional governments was the problem all along.)

Minister Kahlon might have had these critics in mind when he told the Legislature that “in some communities throughout British Columbia, restrictive zoning and delays in development approvals continue to slow down the delivery of homes.”

Although the reforms stop short of where they might have gone, particularly on Vancouver’s west side, they do mark a profound break with the past and a welcome new day in the province.

With transit-oriented areas, missing middle upzoning, parking relaxations, and possible single-stair reform, BC’s government is no longer a laggard behind Oregon and Washington (or Montana, Anchorage, or Boise). Indeed, the province of British Columbia is not only Cascadia’s new abundant-housing-policy leader but has set a new standard for improving affordability and the built environment in North America.

Next—and Sightline will be watching—comes the implementation phase: bringing local rules into compliance with the new provincial reforms.

Adam Buckley

As a BC resident, albeit a rural one, I’m glad that some real progress is being made. And making things more affordable for Vancouver/Victoria residents keeps the rural province affordable as well.

I think I’ve found another option for housing related news. It seems like any Ontario-based national publication tries to align with the speculators when it can get away with it. This site, while not just about housing, could very well be my best option.

Keith Austin

Interesting that the author claims that greater density is about affordability.

Lewis N Villegas

Nice job swallowing the Kool-Aid, Danny. There is a line of thinking out there insisting that ‘building more density’ will end the housing crisis.

Yet, we know that the increase in housing price is ‘all in the land.’ Thus, the focus of new legislation should be ‘increasing access to land,’ instead of throwing up more towers.

Adding more towers will just keep the prices going up and up. Which is what government wants. Since this legislation opens the door to extracting more and more tower revenues.

When we do access more land, we better make sure that good practice in urban design and architecture will be the order of the day. And that neighborhood infill and new towns along modern Streetcar|LRT routes are 2 to 4 stories in height to assure both affordability and high levels of social functioning.

Bills 44, 46 & 47 represent a giant hand-off from government to the developers, professionals, banks and investors. A group that has been profiting from an artificially created housing crisis ever since 1980 when the Skytrain was first planned.

Housing prices are worse every year since then. Building Skytrain has had no visible effect on prices, except perhaps driving them up.

Danny, the other thing that you’ve missed in reading the legislature, is how poorly it is drafted is. On the one hand, there is no awareness that transit stations are hubs for crime, and towers are the worst performers in terms of delivering ‘defensible space.’

On the other, if you go to Europe and visit neighborhoods with one stair, you will notice that the buildings are four storeys or less, with eight units clustering around one stair, two doors per landing.

Transit Oriented Development (TOD) was the creation of New Urbanists in the US, most of whom disavow the need to build towers in neighborhoods (See for example: The Pedestrian Pocket Book: A New Suburban Design Strategy. Doug Kelbaugh. U of Washington, 1989).

Another good read is: The Consequences of Living in High-Rise Buildings. Where U-Vic prof Robert Gifford in 2008 reviewed the psychological literature on high-rise living and found very negative results widely reported.

In order to have good neighborhoods, we must build with forms that support ‘high levels of social functioning,’ rather than towers. Towers are fine in the Downtown Peninsula, a location blessed with mountains to the north, Stanley Park to the west, Beaches on the south, and the downtown to the east. Otherwise, we should build Canada as a mix of houses, row houses and courtyard houses. Even the corridor 3-storey apartments are weak performers in terms of social functioning. The result we are after are… walkable neigbhorhoods, livable streets and affordable houses.

The towers do not make housing more affordable. What we see instead is the size of the units going down. 800 SF is now a 3-bedroom (was two); 600 SF is a 2-bedroom (was one); 425 SF is a one bedroom (was a studio); and 360 SF is a studio (was a roomy closet). Even the ‘minimum’ bathrooms has been cut back from 40 to 37.5 SF.

In order to achieve more reductions in space, the bedrooms barely fit a bed, and kitchen, dining room and living room have been combined into one space, typically measuring just 175 SF. Consider that kitchens were once 60 SF, dining areas 80 SF, and living rooms at a minimum 120 SF. For a total of 240 SF in the smallest of apartments. Thus, 37% of the ‘living space’ has been lopped off in the new towers.

Its like at the food store, where you buy a box of cereal for the same, or slightly higher price, only to find that there is less cereal inside the package.

We also see developers not providing parking, because digging holes in the ground is very expensive. So, now, a tower may provide NO parking (because 20% of the suites will rent at ‘below market’ rates). Or it may provide 100 cars and 300 bike spaces for 180 units. That will lead to more cars parking on the street; more multi-storey garages being built; and more storage locations as well.

The narrative that we will drive less and less should be questioned. As should the claim that Skytrain is anything more than a People Mover.

The Skytrain in Vancouver is 12 more expensive than in Ontario (ION line, Mississauga-Waterloo), and the proposed Langley extension 6-times more.

As a consequence the amount of Skytrain built—the system’s reach—is far below what a regional transit system must deliver. Lower cost technology means more service.

For the price of the Broadway tunnel to UBC we can put modern Streetcar|LRT between Granville Island and Chilliwack—140 km (like Mississauga’s, which is the system demonstrated here at the 2012 Olympics). It would not only serve Langley, but it would serve the Township of Langley and beyond.

For the cost of the Langley extension we could build Streetcar|LRT between Belcara/Port Moody and Agassiz—100 km. Sure, this line would require a bridge over Indian Arm to reach the rest of the North shore. And we need to build a tunnel under the Burrard Inlet for the same purpose. However, once in place, we would have fast and reliable regional service to Whistler and beyond, Chilliwack, and Agassiz (or Hope).

The thing is that each of these three lines would support 1 million new, guaranteed affordable homes, housing a total of 6.6 million people—2.2 million per line.

Following the kind of knowledge available in that TOD book from 1989—35 years ago—we could build towns, or intensify neighborhoods, every 1.5 kilometers.

Each town, measuring 120 acres or a radius equal to 5 min walk from the station, would house 10,000. A 12 minute walk from a station in an existing neighborhood would support infill of 5,000 people. Both build outs, in new towns and exiting neighborhoods, would be at human scale, using buildings 4 storeys or less.

These are the urbanist principles Bills 44, 46 & 47 have nicked to build towers.

Housing 2.2 million people per line of Streetcar|LRT can be of a scale that promotes maximum social mixing. What we call ‘human scale.’ The kinds of villages you see in Europe.

Scale is important because it means we can avoid building corridors and elevators and underground parking.

For example, at four storeys, all units have a front door on the street, square or courtyard. There are no internal corridors (or single stairs—even more savings for builders!). Elevators are only used to access the parking level on developments over 40 units per acre. However, most developments are ‘self-parking,’ using off-street parking at a rate of 1.5 spaces per unit.

If you take the time to read this full response, you will see that what is missing from Bill 44, 46 & 47 (The Towers-and-Skytrain Bill) is a thorough understanding of how to build good cities.

The legislation—I’ve read it—is entirely based on economic calculations. It betrays no understanding of what constitutes good urban form, or how to make good neighborhoods (essentially, the same thing).

I encourage you to research good urbanism, and look for alternatives to Skytrain-and-Towers.

Developers, banks, large professional firms and investors—and government—are making off like bandits. That is what is driving the Skytrain-and-Towers.

However, the neighborhoods that will be created under this legislation will not be good urbanism. Canada can do better than that. We are after all the largest democracy in the world measured by land mass.

We have the resources. What we seem to be lacking in is imagination and knowledge.