In the first article in this series, I showed that Portland city government has a dismal record of representing Portlanders. Nonpartisan elections make it hard to measure the council’s ideological representativeness, but it is easy to measure the lack of racial, ethnic, gender, and geographical diversity. For example, although nearly one-third of Portlanders are people of color, no person of color has served on the council in the past quarter-century, and not a single woman of color has ever held a seat on the council. Half of Portlanders are women, but women have served less than one-quarter of the person-years on the council in the past 25 years. In the second article, I posed seven questions (and short answers) about how Portland could better structure its city government to improve how representative it is of residents.

In this, the third and final article in the series, I lay out eight scenarios for electing the council in single-member districts with top-two voting or in multi-member districts with ranked-choice or cumulative voting. Many other factors influence representation, including money in politics, voting rights, and candidate pipelines, but this article focuses on the important puzzle pieces of election systems and district configurations. Each scenario necessarily makes some assumptions about how people vote. Assumptions underlying all scenarios are spelled out in the appendix.

Portland’s representation problem

Portland uses the least representative electoral method: at-large numbered seats and “vote for one” ballots. At-large numbered seats allow the majority of voters in the city to elect every single member of the council, leaving no room for representation of voters in any minority: racial, ideological, geographic, or otherwise. Switching to districts—the alternative commonly discussed—would prioritize geographical diversity over other kinds. It would guarantee a geographically diverse council but would not necessarily elect more people of color, more women, more renters, or more working-class representatives.

Portland uses the least representative electoral method: at-large numbered seats and “vote for one” ballots.

But if it chose to do so, Portland could become the second US city to adopt the most representative form of voting: multi-member council districts elected with ranked-choice voting. Portland could achieve a balance of geographic, racial, gender, and socioeconomic representation by expanding the council to eight members and electing them from three districts: three councillors from a west-south district, three from a north-northeast district, and two from an eastern district. Or Portland could achieve balance of representation with a slightly smaller council by adding just two council members (for a total of six) and electing three from a west-south district and three from a east-north district.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Let’s go through the options (you may click on each link to jump to its section below):

Single-member districts

Single-member districts yield better geographic representation, which Portland sorely needs. However, single-member districts might do little or nothing for the Rose City’s racial, ethnic, gender, ideological, and economic representation on city council. Single-member districts drawn to create one or more majority-minority districts are a common strategy for remedying violations of the federal Voting Rights Act, which bans election practices that consistently exclude members of racial minorities from representation in elected office. To this end, single-member districts work well in places where people of the same race or ethnicity tend to live in the same neighborhood. In Portland, though, where people of color are very geographically dispersed across the city, it turns out to be impossible to draw even one majority-minority district.

To date, the US Supreme Court has only recognized districts where a single racial group is in the majority and votes together. In contrast, California courts have recognized “coalition districts” where there is evidence that more than one non-white racial groups vote together to elect the same candidate. For example, in the 2006 Democratic primaries for California State Controller and California Insurance Commissioner in San Mateo County, Latino voters overwhelmingly preferred Latino candidate Cruz Bustamante, and both Asian and Latino voters somewhat preferred Bustamante and Asian-American candidate John Chiang over white candidates John Dunn and John Kraft.

As I detail below, though, Portland has no area where people of color, much less any single non-white racial or ethnic group, make up the majority. Consequently, single-winner districts may not increase racial and ethnic representation on the council. In addition, if one district did elect, say, a Latina, she would only represent her district. Latinxs living elsewhere in Portland might feel relieved their interests and life experiences have at least some representation on council, but, especially if she was facing a tough re-election bid, the Latina councilor’s priority would be her own district.

Single-member districts can also have the drawback of promoting “pork-barreling.” Just as councilors under the Commissioner form of government sometimes focus on their own bureaus rather than the city as a whole, a district representative’s job is to represent her district. She may do so to the detriment of a city-wide view.

Finally, Portlanders might feel that a move to single-member districts takes away some of their voting power. Right now, every Portlander gets to vote for every councilor and the mayor. With single-winner districts, voters would only vote for one councilor and the mayor.

Multi-member districts

Multi-member districts elect more diverse councils. In single-member districts, a candidate must win a majority of votes in that district to win a seat on the council. Much of the time in Portland and across the United States, the majority winner is a white male homeowner, and in partisan races, he is from one of the two major parties. Repeat this process in each district, and you could end up with a council made up entirely of white male homeowners with somewhat similar ideological views.

But using ranked-choice voting or cumulative voting in a multi-member district allows a group of voters making up less than a majority in the district to elect a representative who speaks for them—a person who might never be able to win if voters were selecting just one winner. As described further below and in our other work here and here, these election methods have proven to elect more women, more people of color, and more ideologically diverse candidates.

Even in multi-member districts that use Bloc Voting (in a three-member district, voters can “vote for three”), which requires majority support, it turns out that voters seem to be more willing to cast one of several votes for a woman than in single-member (“vote for one”) races where they only have one vote to give. US states that use both single-member and multi-member districts for their state legislatures are much more likely to elect women from the multi-member districts than from the single-member. They also tend to have more women in the legislature than do states with single-member legislative districts. The improvement in female representation appears to stem from voters’ willingness to vote for at least one woman when they have the chance to vote for multiple candidates at a time. It could also be that women are more willing to run as part of a multi-winner slate than as a single-winner individual.

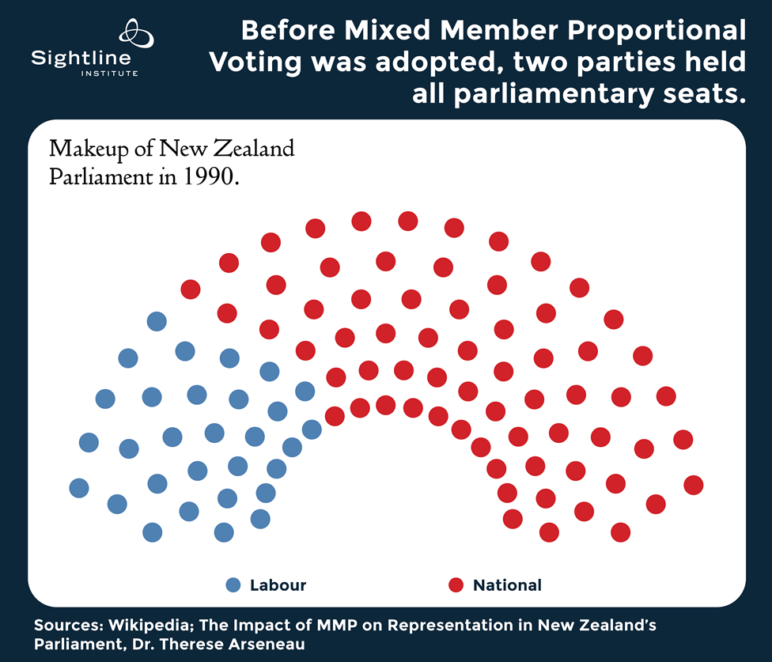

Germany and New Zealand both use a combination of single-member and multi-member districts, and the multi-member districts are almost three times as likely to elect women and twice as likely to elect people of color. This difference is at least partly due to political parties or other political organizers or donors seeing an advantage in a diverse slate of candidates in a multi-winner election, where they often conservatively assume that the most “broadly acceptable” candidate in a single-winner election is a white man.

Ranked-choice voting

Using ranked-choice voting in multi-member districts—a system also called “proportional single-transferable voting”—would let voters express their preference between multiple candidates, electing a city council that reflected the true diversity of Portland. If electing three councilors from a district, the ballot might look like the one below. All candidates for that district would run together in a pool, and voters would rank them in order of preference. First-choice votes would be counted first, and any candidate who reaches the winning threshold (more than 25 percent of the votes in a three-winner race) would earn a seat.

For example, if African-Americans made up 25 percent of voters and they all ranked the same candidate first, that candidate would immediately win a seat. Just so, if voters who wanted the council to prioritize affordable housing made up at least 25 percent of voters and all ranked a champion for affordable housing first, she would win a seat. If she won more than 25 percent of the vote, all of her voters would (automatically, by the vote tallying method) transfer a fraction of their unneeded votes to their next-ranked candidate. If no candidate reached the 25-percent threshold, the candidate with the fewest votes would be eliminated and his votes transferred to his voters’ next-ranked candidate. This would continue until three candidates won. (Here’s a short video that explains multi-member ranked-choice voting.) The city of Cambridge, Massachusetts, has used this method to elect its city council and school board since 1941, yielding impressive and persistent diversity in both bodies.

Cumulative or limited voting

If using a ranked-choice ballot felt too foreign to Portland voters, cumulative or limited voting could offer a more familiar-looking ballot and an improvement in representation of minority groups, though not as proportional in representation as ranked-choice voting. More than 100 cities and school boards across the United States use these methods in multi-winner elections to achieve better representation. In many cases, a court ordered the locality to switch to multi-winner elections as a remedy for a Voting Rights Act violation, especially in places where people of color are geographically dispersed, as they are in Portland.

With cumulative voting, voters have as many votes as there are seats available, but rather than giving one vote to each favored candidate, they can distribute their votes however they wish. For example, in a three-winner election, a voter would have three votes and could give two votes to one candidate and one vote to another. The “Equal & Even” cumulative voting ballot may be easier to understand, allowing the voter to give up to three votes. The difference is that if she only fills one bubble, all three of her votes go to that candidate, and if she fills two bubble, each candidate gets 1.5 of her votes.

Say, for example, Native Americans make up 30 percent of the voters in a three-member city council district. If all of them give all three votes to a candidate they feel represents them, he could win one of the seats and those voters could feel they have fair representation on the council.

In this excerpt from her book, Tyranny of the Majority, civil rights attorney and Harvard law professor Lani Guinier explains why cumulative voting in multi-winner districts may be a better civil rights remedy for people of color than “race-conscious districting” of single-winner districts.

For example, in Martin, South Dakota, Native Americans made up more than one-third of the population yet consistently won fewer than 10 percent of seats in the city’s system of at-large numbered seats (the same system Portland uses now). In 2008, a federal court ordered the city to eliminate numbered seats and instead let candidates run in a multi-winner pool for three seats at a time. Voters have three votes and can assign one, two, or all three of them to any candidate(s) in the pool. Native Americans voters can express strong support for Native American candidates and now consistently win fair representation on the council.

As another example, African-Americans were chronically under-represented in the city council of Peoria, Illinois, until a civil rights lawsuit prompted the city to switch in 1991 to multi-winner races with cumulative voting. African-Americans have consistently won representation ever since.

With limited voting, each voter gets fewer votes than there are seats available. For example, if Portland were electing all five councilors at once, voters might get two votes each. If electing three councilors at a time, each voter would get one vote among the pool of candidates.

Cumulative and limited voting are inferior substitutes for ranked-choice voting, because they are more vulnerable to vote splitting. That is, if more than one candidate of color runs and voters split their votes between the two, both could lose under cumulative or limited voting, but one would win under ranked-choice voting. Still, they are better than the status quo in Portland.

Number of voters needed to win a seat

One of the challenges with using at-large elections in a larger city like Portland is that candidates must canvass a large area and win a lot of votes to get a seat on the council. If 250,000 people vote, a city council candidate needs more than 125,000 votes to win. (For comparison, 260,448 Portlanders voted in the November 2016 city council race.)

All of the single-member and multi-member district scenarios below drastically reduce the number of votes a candidate must win to get a seat on the council. This reduced burden could open the door for new candidates to run.

In a multi-winner ranked-choice election, a candidate needs to win 1/(Number of seats + 1) of votes in the district to win a seat. If Portland expanded the council to six members and elected them in two three-member districts, each candidate would need at least 1/(3+1) = 25 percent of one-half of 250,000 = more than 31,250 votes to win a seat. If Portland expanded the council to eight members and elected them in two three-member districts and one two-member district, each candidate in a three-member district would need at least 1/(3+1) = 25 percent of three-eighths of 250,000 = at least 23,438 votes to win a seat.

The chart below shows the minimum number of votes each candidate would need to win a seat in each district scenario. In almost all district scenarios, candidates would need around 20,000 to 30,000 votes to win; that’s one-quarter or less of the minimum 125,000 votes they would need to win under current rules.

The lower threshold to win guarantees greater ideological diversity on the council, because candidates with minority views can win a seat by appealing to the tens of thousands of voters who share those views, rather than trying to reach more than one-hundred-thousand voters. It also might make it easier for new candidates to enter the race. A community organizer without broad name recognition or a big rolodex might be able to round up 30,000 votes in North and East Portland. Changing to any of the district options below might usher in a new crop of council candidates.

Portland scenarios

That covers the voting methods and explains the thresholds to win, now let’s map out some scenarios for Portland—specific combinations of district and election methods, and how they would affect representation of people of color, women, and East Portlanders—all groups chronically under-represented on city council. The multi-member district scenarios below all assume ranked-choice voting or cohesive cumulative voting, and all assume people of color all vote for candidates of color. While this is, of course, not necessarily true because people of color are not monolithic, using the same assumption across scenarios makes it possible to compare them against each other in terms of potential diversity of representation. Other assumptions for all scenarios are listed in the appendix. We’ll look at (here, again, you may click on each scenario to jump to its section below):

In all of the maps below, each dot equals 50 people counted in the 2010 census, color-coded by census categories of race and ethnicity:

- Blue dots are non-Hispanic African-Americans;

- red dots are Asians, Hawaiians, or Pacific Islanders;

- yellow dots are Latinos or Hispanics;

- orange dots are Native Americans; and

- green dots are non-Hispanic whites.

The result is a visual depiction of where people are densely concentrated within Portland (The Pearl), which neighborhoods are mostly white (Southwest), which have a larger African-American population (North Portland), and which have larger Asian and Latino populations (East Portland).

Current council: Four at-large numbered seats

Portland uses at-large numbered seats to elect each of the four councilors. The council’s fifth member, the mayor, is also elected at-large. Voters vote for one candidate for each seat. Even though there are two council seats available in an election year, voters don’t have the option to choose their favorite two candidates, but must choose one from one list and one from the other. For example, in 2012 some voters might have wanted to vote for both the women on the ballot—Amanda Fritz and Mary Nolan. But voters were forced to choose just one because they were running for the same numbered seat.

Portland’s city council makeup doesn’t match that of its residents. For instance, although fewer than one-quarter of Portlanders live west of the Willamette River, four of five current council-members do. And although nearly one-third of Portlanders are people of color, four of five council-members live in neighborhoods that are less than one-sixth people of color. Nearly half of Portlanders rent, but four of five council-members come from neighborhoods where over 70 percent of people own their homes.

| Current Council |

|

|

|

|

Number out of Total Council |

Percent of Council |

Percent of ____ with ____ representing them* |

| People of Color |

0 of 5 |

0% |

0% |

| Women |

2 of 5 |

40% |

100% |

| East Portlanders |

0 of 5 |

0% |

0% |

*In this and all the tables below, this column means: Percent of people of color with a person of color representing them on council; percent of women with a woman representing them on council; percent of East Portlanders with an East Portlander representing them on council.

Single-member district scenarios

Four single-member districts

If Portland elected its four councilors from four single-member districts, the districts might look like the map below. The eastern district would have the most people of color: 37 percent. If we assume (as all scenarios do—see the appendix for more details) that all voters turn out in equal numbers and all voters of color prefer the same candidate of color, then to elect a person of color in that district, at least 13 percent of white voters would need to join voters of color in electing her. The northern district would have 33 percent people of color, so could elect a person of color if at least 17 percent of white voters voted for her. In other words, the odds of electing a councilor of color would be somewhat higher than in the current, all at-large situation, but not by much. Each district would have a chance of electing a woman, but, based on past Portland elections, women would likely win zero or 1 seats, possibly two. East Portlanders would be guaranteed a representative.

| Four Single-Member Districts |

|

|

|

|

Number out of Total Council |

Percent of Council |

Percent of ____ with ____ representing them |

| People of Color

-if 5% of white voters vote for PoC

-if 15% of white voters vote for PoC |

0 of 5

1 of 5 |

0%

20% |

0%

34% |

| Women |

0-2 of 5 |

0-40% |

0-50% |

| East Portlanders |

1 of 5 |

20% |

100% |

Six single-member districts

If Portland expanded the council from five to seven members and elected six councilors from single-member districts and the mayor city-wide, the districts might look like what’s in the map the below. The eastern and northern districts would be 38 and 36 percent people of color, allowing them each to elect a person of color if at least 12 and 14 percent, respectively, of white voters also voted for the candidates of color. Voters in the other four districts would, using these assumptions, have white representatives. Each district would have a chance of electing a woman, but, based on past Portland elections, women would likely win less than half the seats and might even win zero seats. East Portlanders would be guaranteed a representative.

| Six Single-Member Districts |

|

|

|

|

Number out of Total Council |

Percent of Council |

Percent of ____ with ____ representing them |

| People of Color

-if 5% of white voters vote for PoC

-if 15% of white voters vote for PoC |

0 of 7

2 of 7 |

0%

28% |

0%

45% |

| Women |

0-3 of 7 |

0-43% |

0-50% |

| East Portlanders |

1 of 7 |

14% |

100% |

Eight single-member districts

If Portland expanded the council from five to nine members and elected eight councilors from single-member districts and the mayor city-wide, the districts might look like the map below. The eastern and two northern districts would be 38, 37, and 36 percent people of color, allowing them each to elect a person of color if at least 12, 13, and 14 percent, respectively, of white voters voted for the candidates of color. In other words, even expanding to a nine-member council would not get Portland close to a majority-minority district. Each district would have a chance of electing a woman, but, based on past Portland elections, women would likely win less than half the seats and might even win zero seats. Portlanders east of 122nd would be guaranteed a representative.

| Eight Single-Member Districts |

|

|

|

|

Number out of Total Council |

Percent of Council |

Percent of ____ with ____ representing them |

| People of Color

-if 5% of white voters vote for PoC

-if 15% of white voters vote for PoC |

0 of 9

3 of 9 |

0%

33% |

0%

45% |

| Women |

0-4 of 9 |

0-44% |

0-50% |

| East Portlanders |

1 of 9 |

11% |

100% |

Multi-member district scenarios

One city-wide four-member district

Portland could maintain its current number of just four councilors and elect all of them in a single city-wide pool. Voters could rank their preferences or have four votes on a cumulative ballot. If the 2012 election where Portland voters were limited to choosing between Amanda Fritz and Mary Nolan had instead been a four-winner election with ranked ballots, voters would have seen all the candidates in a single list and been able to rank them: maybe Amanda Fritz first, Mary Nolan second, Jeri Williams third, Steve Novick fourth, Leah Marie Dumas fifth, and so on.

In a four-winner race, the threshold to win is 20 percent of the vote plus one. Using the same assumptions as above, people of color could easily elect one councilor, even with low turnout or un-cohesive voting. With cohesive voting plus support from 10 percent of white voters, people of color could elect two of the four councilors. In other words, assuming exactly the same voter behaviour in both scenarios, one four-member district would elect one or two (out of five total, including the mayor) councilors of color while four single-member districts would elect zero or one. In a four-winner election, women would almost certainly win at least one seat, and all Portlanders would have at least one woman representing them. If they voted together for an East Portlander, East Portlanders could also easily elect a councilor.

Further, if the election were held in a high-turnout presidential election year, it would maximize the number of Portlanders with a say in electing every councilor, because no councilors would be elected in the lower-turnout midterm years.

| One District with Four Members |

|

|

|

|

Number out of Total Council |

Percent of Council |

Percent of ____ with ____ representing them |

| People of Color

-if 5% of white voters vote for PoC

-if 15% of white voters vote for PoC |

1 of 5

2 of 5 |

20%

40% |

100%

100% |

| Women |

1-2 of 5 |

20-40% |

100% |

| East Portlanders |

1 of 5 |

20% |

100% |

Two districts with three members each

If Portland split into two districts—a west-south (W-S) district and an east-north (E-N) district—the districts might look like the below map. If the council expanded to six members, Portlanders would elect three councilors from each district, and a voting bloc making up at least one-quarter of each could elect a councilor. In other words, if at least one-quarter of W-S voters wanted a candidate who would focus on better management of the city’s infrastructure, they could elect him. If at least one-quarter of E-N voters wanted a candidate who would focus on improving the city’s treatment of homeless people, they could elect her.

Using the same assumptions as before, if 10 percent of white voters in W-S voted for a candidate of color in addition to all voters of color, the W-S would elect a representative of color. More than one-third of the people in the E-N district would be of color, so they could easily elect one representative of color, and with votes from 13 percent of white voters, they could elect two. At least half, and likely all people of color in Portland would have a representative of color they could call. In a three-winner election, women would almost certainly win at least one seat in each district. Two three-member districts would guarantee geographic balance: three councilors would have to come from the E-N part of the city, and if the 26 percent of Portlanders living east of 82nd all voted for a candidate promising to represent the concerns of east Portland, they would elect her.

| Two Districts, Three Members Each |

|

|

|

|

Number out of Total Council |

Percent of Council |

Percent of ____ with ____ representing them |

| People of Color

-if 5% of white voters vote for PoC

-if 15% of white voters vote for PoC |

1 of 7

3 of 7 |

14%

43% |

67%

100% |

| Women |

2-4 of 7 |

28-57% |

100% |

| East Portlanders |

1 of 7 |

14% |

100% |

Two districts with four members each

If Portland split into the same two districts as above but elected four councilors from each district, then a voting bloc making up at least one-fifth of each could elect a councilor. Using the same assumptions again, the W-S district would elect a candidate of color, and the E-N district would elect two. In a four-winner election, women would almost certainly win one or more seats in each district. This system would also guarantee geographic balance: four councilors would have to come from the E-N part of the city, and if many of the 26 percent of Portlanders living east of 82nd voted together, they would elect a councilor from east of 82nd.

| Two Districts, Four Members Each |

|

|

|

|

Number out of Total Council |

Percent of Council |

Percent of ____ with ____ representing them |

| People of Color

-if 5% of white voters vote for PoC

-if 15% of white voters vote for PoC |

3 of 9

3 of 9 |

33%

33% |

100%

100% |

| Women |

2-4 of 9 |

22-44% |

100% |

| East Portlanders |

1 of 9 |

11% |

100% |

A three-member district and a five-member district

Portland could expand the council to eight members plus the mayor and split into two uneven districts: the W-S district, electing three councillors, and the E-N district, electing five. The winning threshold in the W-S would be 25 percent, and in the E-N it would be 17 percent. This would allow for greater diversity of representation within the E-N district.

The E-N would likely elect two councilors of color and two women, while the W-S could elect one of each. East Portland would almost certainly elect a councilor: 26 percent of voters live east of 82nd, and less than half of them could come together to elect one of the five E-N councilors.

| Two Districts, Three and Five Members |

|

|

|

|

Number out of Total Council |

Percent of Council |

Percent of ____ with ____ representing them |

| People of Color

-if 5% of white voters vote for PoC

-if 15% of white voters vote for PoC |

2 of 9

3 of 9 |

22%

33% |

77%

100% |

| Women |

2-5 of 9 |

22-55% |

100% |

| East Portlanders |

1 of 9 |

11% |

100% |

Three districts with two or three members each

Portland could expand the council to eight members plus the mayor and split into three districts like the ones in the map below: the W-S and E-N districts, each electing three councillors, and a third East (E) district, electing two. The winning threshold in the W-S and E-N would be 25 percent, and in the E it would be 33 percent.

This arrangement would guarantee geographical diversity and would generate districts almost as geographically small as four single-member districts, possibly making it less intimidating for new candidates to run. But it would also ensure greater diversity of representation—in terms of gender, race, and ideology—within each district and on the council as a whole. Each district could elect one councilor of color, and possibly a woman. Two councilors would come from east of the 205.

| Three Districts—Three, Three, and Two Members |

|

|

|

|

Number out of Total Council |

Percent of Council |

Percent of ____ with ____ representing them |

| People of Color

-if 5% of white voters vote for PoC

-if 15% of white voters vote for PoC |

2 of 9

3 of 9 |

22%

33% |

71%

100% |

| Women |

2-5 of 9 |

22-55% |

75-100% |

| East Portlanders |

2 of 9 |

22% |

100% |

Conclusion

Single-member districts would improve the geographic representation of Portland’s city council. But single-member districts might do very little to improve racial, ethnic, gender, economic, or ideological representation on the council. From the voters’ perspective, single-member districts would lead to fewer Portlanders having a woman representing them on the council, and even if one single-member district elected a person of color, the majority of Portlanders of color would still be without a councilor of color actually representing them.

Multi-member districts are a proven remedy for electing more diverse representatives—in particular, more people of color and more women. Indeed, all the multi-member scenarios above make it likely Portland would see at least one and usually more people of color on the council, and that most Portlanders of color would have a councilor of color actually representing them. By letting voters choose more than one candidate from a pool, all multi-member district scenarios make it more likely that at least one and maybe more women would be elected to the council in every election. Multi-member districts also guarantee some level of geographical diversity, both by breaking the city into smaller chunks and by letting a minority of voters with a common interest—for example, making sure East Portland has a voice—band together to elect a representative.

A more diverse council would also represent more views that Portlanders hold. For example, if around one-quarter of voters thought people-friendly streets were a top priority, they could, in a multi-member district, elect a safe streets champion, or an advocate for good city management, or a councilor who would push for other particular reforms that voters wanted. Portland reformers should consider multi-member districts as a way to elect a more diverse council in terms of race, ethnicity, gender, geography, and political priorities.

Appendix: Assumptions in all scenarios

Each scenario includes a table predicting how many people of color, women, and candidates living east of 82nd might be elected. These tables don’t purport to make actual predictions. But each scenario can be compared against the other scenarios because each scenario uses the same set of assumptions. Namely:

- The 2010 census is accurate. (In reality, the census often undercounts people of color. In addition, Portland’s population of color is growing, and the areas with high concentrations of people of color are shifting from North Portland to East Portland.)

- All racial and ethnic groups turn out to vote in equal numbers in all elections. (In reality, white voters often turn out more heavily, especially in primary and midterm election years.)

- Everyone who marked a census box for anything other than “white alone, non-Hispanic” is a person of color. (Some white Latinos or people of mixed racial or ethnic heritage might not identify as people of color.)

- Everyone who marked a census box for “white alone, non-Hispanic” is white. (For example, Portland’s Coalition of Communities of Color includes Slavic people, who would be white on the census but might identify as people of color.)

- All people of color vote in a bloc for any candidate of color. (People of color are not monolithic. American voters tend to vote for a candidate of their race or ethnicity, but voters of color might not vote for a candidate of color of a different race or ethnicity. In the United States, Latino voters usually strongly prefer Latino candidates, but Latino voters might not vote for an African-American candidate, and vice versa.)

- All multi-member districts use ranked-choice ballots, and voters of color rank candidates of color first. Or, if using a cumulative ballot, voters of color put all their votes toward electing the same candidate of color.

- Within each scenario, each table shows two cases. In the first case, 5 percent of white voters vote for the candidate of color. In the second case, 15 percent do. (All else equal, white American voters tend to vote for white candidates, so this assumes that some voters either don’t follow that trend or feel the candidate of color’s policy position hew most closely to their own views.)

- Except for the five- and nine-district maps that attempt to draw a majority-minority district, most maps try to follow existing geographic or political boundaries, as required by the Oregon Secretary of State’s districting directive, with which local governments must comply when drawing districts.

- In a single-winner election, women fare about as well as they have in past Portland elections, with a roughly 0-40% chance of winning. In a three-winner election, women win one seat. In a four-winner election, women win one or two seats. In a five-winner election, women win two or three seats. (US states that use multi-winner elections for their state legislatures are much more likely to elect women than in single-winner elections, likely at least in part because voters often include at least one woman when they have the chance to vote for multiple candidates at a time.)

- All voters living east of 82nd vote in a bloc for a candidate living east of 82nd.

- Portland elects an even number of councilors and separately elects a mayor who also has a seat on the council.

Thanks to CORE GIS for creating the maps in this article.