Although Oregon has been a laggard in strengthening pesticide regulations, a set of bills that would shield humans and ecosystems from their potentially dangerous effects is now before state lawmakers.

If passed, Oregon would rank among the most assertive states for protecting communities from pesticides. The bills, SB 853 and HB 3058 among others, have key endorsements from Beyond Toxics and the Oregon Conservation Network as part of their pesticide policy reform campaign. Both address major obstacles that today prevent local communities from protecting themselves and their ecosystems from potentially harmful substances.

If passed, Oregon would rank among the most assertive states for protecting communities from pesticides.

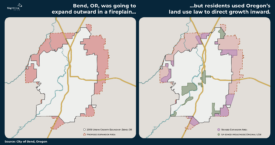

One set of bills would prohibit aerial spraying over state forests and update Oregon’s online notification system for pesticide spraying and other forestry activities. Hearings are expected to happen in April. If the state bans aerial spraying, it would be a huge win for Lincoln County, Oregon, whose citizens banded together in 2017 to pass a ballot measure that would ban aerial pesticide spraying. Though their initiative was successful, it is wrapped up in a court battle and, for at least the time being, can’t take effect.

The other set, HB 3058 and SB 853, would ban chlorpyrifos, and restrict use of neonicotinoid pesticides (“neonics” for short) in Oregon. The organophosphate is a well-documented hazard to the nervous systems of children and wildlife. So far Hawaii is the only other state to supersede the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and ban its use. State legislative committees have scheduled hearings to consider the chlorpyrifos/neonic bills March 26, and members of the public can in the meantime submit comments.

Imidacloprid. US National Library of Medicine (Public domain)

Oregon’s legislative consideration of chlorpyrifos is timely, given the long overdue response from federal regulatory bodies. The US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ruled in August 2018 in favor of a coalition of a Hispanic community and several environmental groups. The court found “no justification” for the EPA to continue allowing chlorpyrifos uses “in the face of scientific evidence that its residue on food causes neurodevelopmental damage to children.” It directed the agency to prohibit all uses of that pesticide within 60 days but the Trump administration filed an appeal on that decision less than a month later.

Under federal pesticides law, states cannot set standards less stringent than those established by the EPA, but they can establish more protective standards. Hawaii became the first state to ban chlorpyrifos and the prohibition went into effect in January 2019 with a provision allowing users to apply for temporary extensions. But in any event, this chemical poison may not be used within the Aloha State after 2022. Oregon now has an opportunity to follow suit.

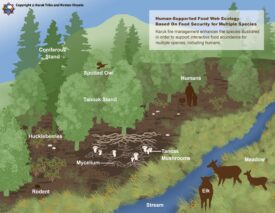

Neonics are chemical cousins of nicotine and the pesticide industry markets them as deadly to insects but much less toxic to humans. The neonic imidacloprid has become the most widely used insecticide in the world. The EPA granted “conditional” approval to imidacloprid in 1994 and later to other neonics, but the agency allowed use on crops without fully evaluating their effects on “non-target” organisms, including bees and other beneficial insects. Not until 2016 did the EPA acknowledge that imidacloprid could harm bees. Consequently, neonics may very well be connected to the precipitous decline in bee populations. In October 2017, the Natural Resources Defense Council sued the EPA for approving neonics without first considering harm to endangered species.

The European Union (EU) follows the “precautionary principle” in setting protective standards on foods; and in May 2018 banned outdoor uses of the world’s three top-selling neonics, including imidacloprid. In 2018, Canada proposed to phase out the same three neonics over the next three to five years. Back in Oregon, Portland and smaller cities have prohibited or otherwise restricted neonic use on their own public properties, but state preemption severely limits the ability for localities to control pesticide use in their communities. For these counties, cities, and towns, this legislation would provide wider restrictions and potentially save them from going up against the Goliath pesticide industry.

It behooves the pesticide industry to restrict localities from taking a more cautious approach to their application. And the industry’s lobbying buys more influence at the state and federal levels. Now, Oregon lawmakers have an opportunity to confer a two-fold benefit on their constituents: allowing local governments to protect their communities and correcting EPA’s mistakes by canceling chlorpyrifos and setting other limitations on pesticide use.

John Abbotts is a Sightline research consultant.

Johanna Turitto

Banning these poisons is the right thing to do now.

John Abbotts

Hello Johanna,

Thank you for your comment and your interest in Sightline’s work