If you live in Washington state, it’s just about guaranteed that you or someone you know is struggling with the cost of housing. This isn’t just an I-5 corridor problem either. Crosscut reported last week that the most drastic percentage increases in prices and rents over the past several years are in Washington’s smaller cities and rural areas, on both sides of the mountains.

Opinion research bears this out as well. Over several years, in poll after poll after poll, Washingtonians have ranked housing affordability, the cost of living, and homelessness among their top concerns. Seventy-six percent of the 6,000 respondents in a Department of Commerce and Puget Sound Regional Council-commissioned survey from late 2022 said they were directly impacted or knew someone directly impacted by the cost and availability of housing in the state.

Washingtonians agree we have a big problem, even if we haven’t always found consensus about how to fix it. But that is changing. The overriding signal from a new statewide poll, commissioned by Sightline and conducted in mid-January 2023 by a bipartisan research team, is that a range of solutions to add more housing, including zoning reform to allow multifamily housing in single-family neighborhoods, is not just palatable; it’s popular. And it’s broadly supported. Favorability toward allowing more homes of all shapes and sizes in Washington cities spanned partisan and demographic lines and held strong across urban, suburban, and rural areas.

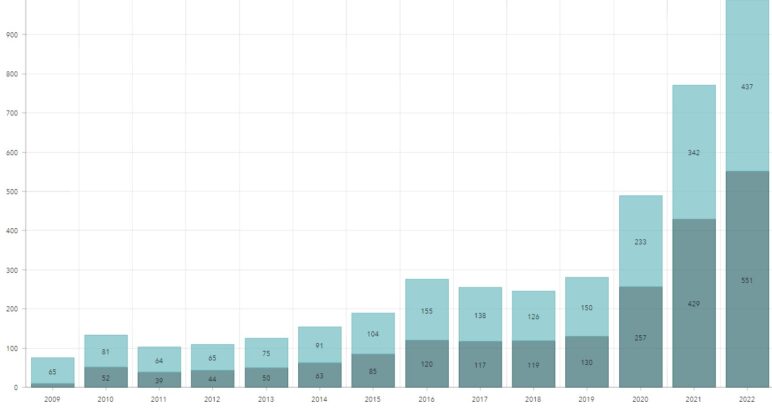

Support to allow more homes, lifting single-family zoning rules, ballooned in the last year alone

Sightline conducted a similar survey a year ago, finding that majorities approved of zoning changes to allow more middle housing and backyard cottage options: a respectable 61 percent supported a generic zoning reform proposal. This year, we expected some movement of public opinion. With greater urgency comes intensifying public will for action.

But the evolving mainstream mindset surpassed our expectations. In 2023, we saw higher support for pro-housing solutions, by more than ten points in many cases. Support for statewide pro-housing policy is rising, from lukewarm to blazing.

What’s more, we more rigorously stress-tested those views this time around, doubling down on the political hot potatoes: namely, a) explicitly stating that the policy would eliminate single-family zoning laws and b) checking people’s tolerance for new housing being built in their neighborhoods. As expected, some support did drop away (those potatoes are hot for a reason), but robust majority support remained.

Today we can say that when it comes to reforming zoning to allow more homes in our cities, including changes that critics have insisted were doomed to be perpetually controversial, strong majorities of Washingtonians are on board.

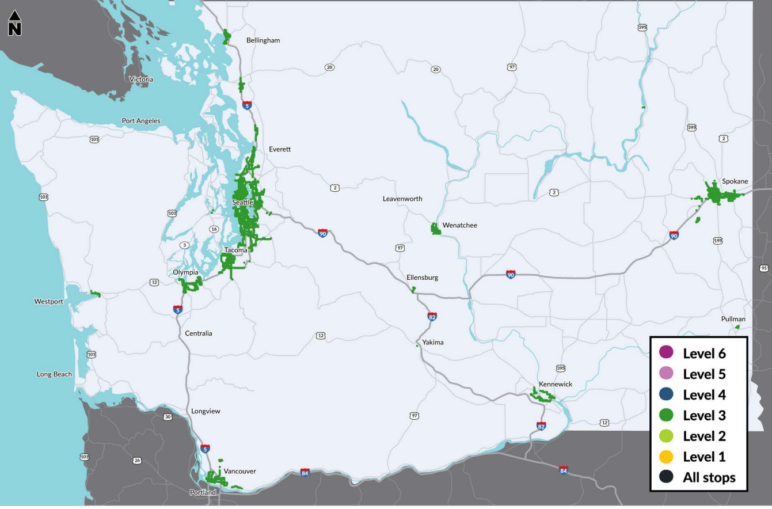

Washingtonians want more homes near transit and jobs, support multifamily options

A whopping 88 percent of likely voters agree that to keep Washington communities affordable, cities should allow housing of all kinds near public transit and jobs.

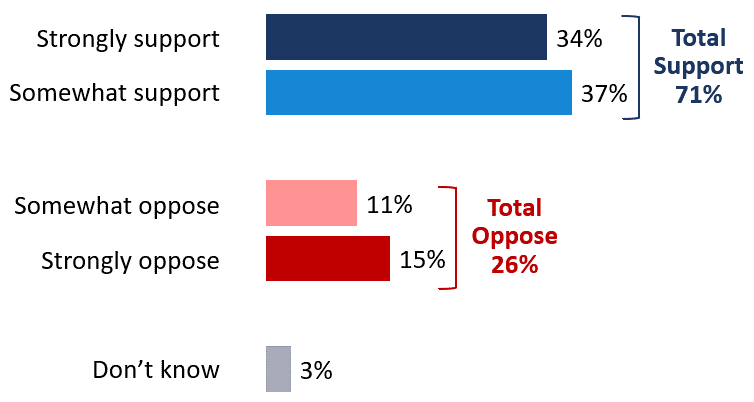

Survey respondents were also presented with a proposal to change state law and zoning requirements to eliminate local zoning laws that allow only single-family houses in cities and towns with populations over 6,000 to facilitate the development of multifamily housing. Seventy-one percent said they would support this proposal, with over one-third (34 percent) “strongly” in favor. Support cuts across partisan, demographic, and geographic lines, including:

- 82 percent of Democrats, 62 percent of independents, and 62 percent of Republicans;

- 80 percent of white voters and 82 percent of voters of color; and

- 79 percent of voters in cities, 75 percent of suburban voters, 64 percent of small-town voters, and 59 percent of rural voters.

Support proved durable in the face of positive and negative messaging about that proposal, too. Seventy-two percent of voters still said they would support the proposal even after hearing an exchange of typical arguments for and against it.

Support for Zoning Reform Proposal

I would like to ask you about a new proposed law related to zoning in Washington. This proposal would change state law and zoning requirements to eliminate local zoning laws that allow only single-family houses in cities and towns with populations over 6,000. It would allow more homes like duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes, and townhouses, including housing more affordable for lower- and middle-income families, near public transit lines, and in areas with a lot of jobs.

And support held when pollsters raised the stakes, making people think about new housing going up near them:

And support held when pollsters raised the stakes, making people think about new housing going up near them:

- 68 percent of Washington state voters say they would support zoning changes in cities statewide even if it meant multi-unit housing developments in their neighborhoods.

- 61 percent of voters in the state would support policy to change zoning rules to allow more housing in Washington cities, even if the new housing, like a duplex or triplex, happened next door.

Washingtonians see housing shortage as top cause of high prices, prefer affordability solutions over “local control”

Voters see Washington’s housing shortage as the top driver of the affordability crisis. Seventy-two percent of respondents say a shortage of housing is a “major” cause of the state’s soaring housing costs.

In addition, a majority (66 percent) believes zoning rules like parking, design, and environmental requirements contribute to high costs. Seventy-three percent cite “too few housing choices of different sizes and kinds” as a cause, but only 38 percent see that as a “major” factor. And to be fair, voters were liberal in assigning blame for high housing prices to a wide range of factors, from wages being too low to landlords’ profits to population growth. But a shortage of homes driving up costs topped the list—ten points above any other factor.

When it comes to questions of “local control” over housing development and residential zoning decisions, a persistent dog whistle housing opponents sound against statewide policy efforts, Washingtonians appear to be out ahead of their local elected leaders.

- 68 percent of Washington voters believe having a range of home types to promote affordability is a higher priority than allowing neighborhoods to control housing types.

- By a 40-point margin, Washington voters prioritize allowing a range of housing types (68 percent) over maintaining strict local control (28 percent).

- Given a choice, 57 percent favor property owners’ right to build housing without strict restrictions versus local governments’ right to strictly limit types, size, and location of housing (35 percent).

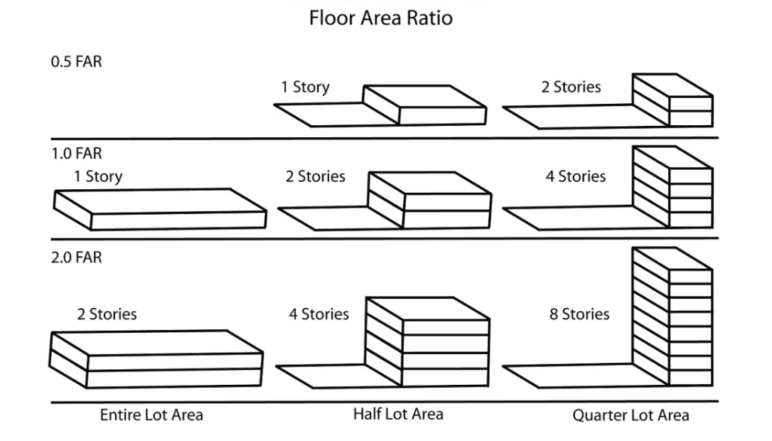

Washingtonians favor range of options, from zoning for ADUs to small and medium-sized apartment buildings

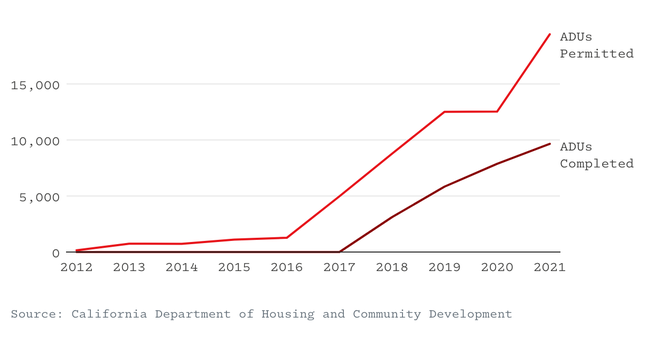

Voters favor adding just about every housing type, from the smallest and least obtrusive accessory dwelling unit (ADU)— also known as backyard cottages, in-law suites, or granny flats, tucked into existing buildings and neighborhoods—to taller multifamily buildings.

This embrace of apartment buildings marks a significant shift. Past polling has generally revealed near-universal love of ADUs (as we saw again in our poll this year), mild support for more modest-sized buildings, like duplexes and triplexes, and then a line drawn when it came to bigger multi-family housing like apartment buildings. The mood has improved in 2023 for a wider range of middle housing types, with a jump to more than eight in ten respondents favoring mid-sized apartment buildings:

- 88 percent of Washington voters favor zoning changes allowing people to add more ADUs on any residential city lot where only single-detached housing was previously allowed.

- 82 percent of Washington voters favor zoning changes allowing more small and medium-sized apartment buildings within existing cities.

- 82 percent of Washington voters support allowing more kinds of housing near frequent bus and train stops, including 4- and 6-story residential and commercial buildings.

- 66 percent support allowing people to split residential lots and build two houses where just one was previously allowed. This is solid support considering that to most, lot-splitting is a new and unfamiliar concept.

Beyond the shortage and zoning, real families and faces

The statewide housing shortage isn’t just an abstract concept for people who call Washington home. Residents are living it, whether it’s their own family and friends or people they rely on in their communities. It’s costing people in long commutes, traffic, increasing homelessness, businesses that can’t find workers, and pressure on housing development to sprawl into the state’s farmland and rural areas.

This survey signals that Washingtonians want this to change. Housing remains a dire priority—with urgency mounting. More and more, voters understand that a shortage is the major factor keeping prices and rents high. And while most Washington voters don’t likely spend too much time thinking about how local zoning restrictions are driving the shortage, they are clearly eager for more housing—including more apartments, triplexes, and backyard apartments—just the kinds of homes that zoning reforms can deliver. The question remaining is whether their state and local leaders will work together to deliver those homes.