Editor’s note: Guest author David Neiman is a principal at Neiman Taber Architects, where he is deeply involved in micro-housing as an architect, developer, and proponent in the public policy sphere. His firm works to create plentiful, high-quality, small unit housing, designed to support livability and promote community among residents.

I’ve spent much of the last decade designing and developing micro-housing projects in Seattle. I’ve also become deeply involved in local and state policy debates around regulating this type of housing. During this time, I’ve witnessed a shift in how micro-housing is viewed and managed: beginning as a novelty and quickly evolving from a developer’s workaround to the neighborhood advocates’ nightmare, to the politicians’ headache and the bureaucrats’ bogeyman, all the while being slowly driven towards extinction by over-regulation.

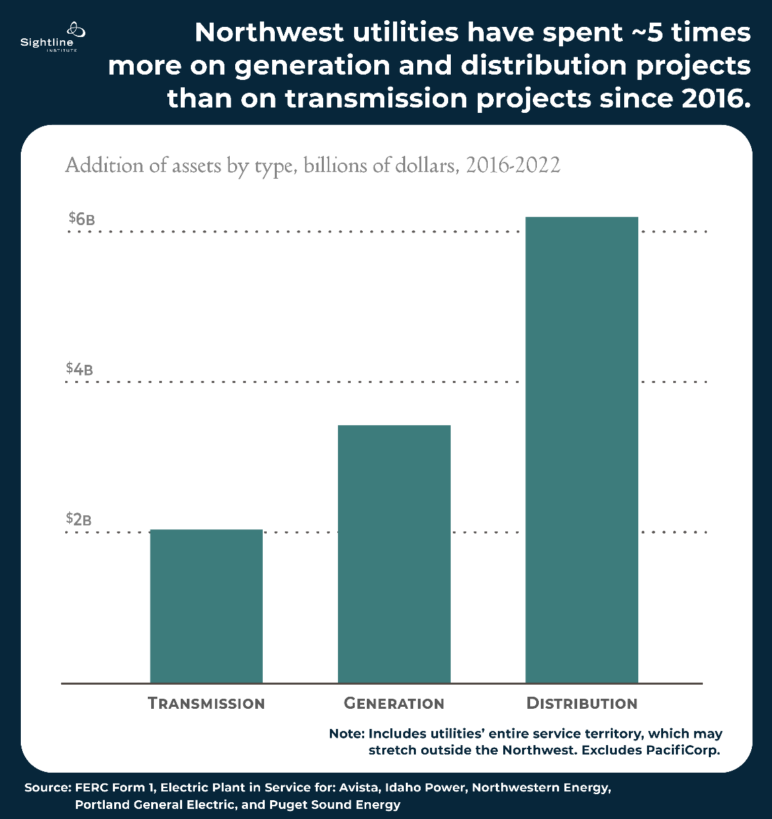

Despite this, and over the din of the loudest voices at the political extremes, I’ve seen a consensus emerge in policy circles recognizing that micro-housing is one of the simplest and most straightforward ways to put more homes into a housing market that is simply starving for them. It’s also one of the most effective ways to give people of modest means the opportunity to live in desirable neighborhoods with access to jobs, services, education, amenities, arts, culture, and an overall high quality of life.

At all levels of government, politicians and policymakers are looking for ways to promote more of this type of housing. But they stumble on the question of “how small is too small,” where to look for guidance, and how to develop appropriate regulations that govern the size of micro-housing. Below I share key resources to inform this conversation, as well as a number of designs to help leaders envision how these homes could look and feel for the many neighbors who need them. Spoiler alert: A well designed studio apartment can be a lot smaller than most people think.

Building codes over zoning codes; Or, health and safety over opinions

First things first: it’s important to differentiate between building codes and zoning codes. Building codes regulate unit size by directly specifying minimum square footage of the floor area. Zoning codes take a more circumspect approach, using density limits, parking requirements, and per unit amenities that indirectly govern housing size.

For the purposes of this article, we will ignore zoning codes, which are inherently political documents that vary from city to city. Instead, we’ll focus on the International Building Code (IBC), which is used in all 50 US states. It has a narrower mandate, which is simply (but importantly) to protect public health and safety and to safeguard against hazards in the built environment. While in practice, the ultimate rationale for a zoning code provision can be merely “because I said so,” the building code is supposed to have an empirical justification and so can be evaluated on that basis.

The IBC regulates housing size by dictating the minimum size of “habitable” rooms. For instance, a studio apartment requires a 190-square-foot living room. Additionally, the IBC mandates that a kitchen, a bathroom, and a storage closet be provided. Combining those elements with the code-required circulation and accessibility clearances, a studio apartment’s minimum size usually ends up at about 300 square feet.1

A 300-square-foot studio apartment is by no means luxurious, but smaller apartments are quite common, and I would guess that most of us have lived in smaller spaces at one time or another. In Seattle, a 300-square-foot studio rents for approximately $1,600 per month, making it affordable for people earning around $64,000 annually. That’s fine if you can afford it, but nearly half of Seattle’s renters can’t afford to pay that much for rent.

To serve these neighbors, either we need to build housing that is smaller and more affordable than what conventional development can deliver, or we need to provide subsidized housing to a large percentage of our population. Realistically, our present social safety net can’t even provide for our most vulnerable populations, let alone people who are fully employed but simply earn a modest salary. This is where micro-housing can play a crucial role.

Imagining a new micro-housing norm

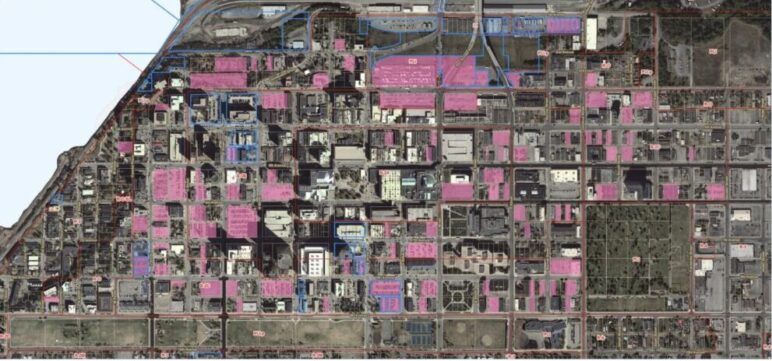

Of Cascadia’s major cities, I’m most familiar with Seattle, which has been a national leader in micro-housing. In recent years the city has built thousands of micro-homes in various forms. One type is a smaller studio apartment that Seattle calls a Small Efficiency Dwelling Unit (SEDU). This type of housing has been legal for over 20 years, offering residents smaller and more affordable alternatives to traditional studios.

Housing advocates in Washington are working on legislation this year to legalize this kind of small studio apartment throughout the state. But to get there, legislators and policymakers first need to understand that this type of housing is humane, safe, and dignified. To show that, let’s compare what the code allows today to some smaller, more affordable alternatives.

Status quo: Today’s typical micro-housing studio

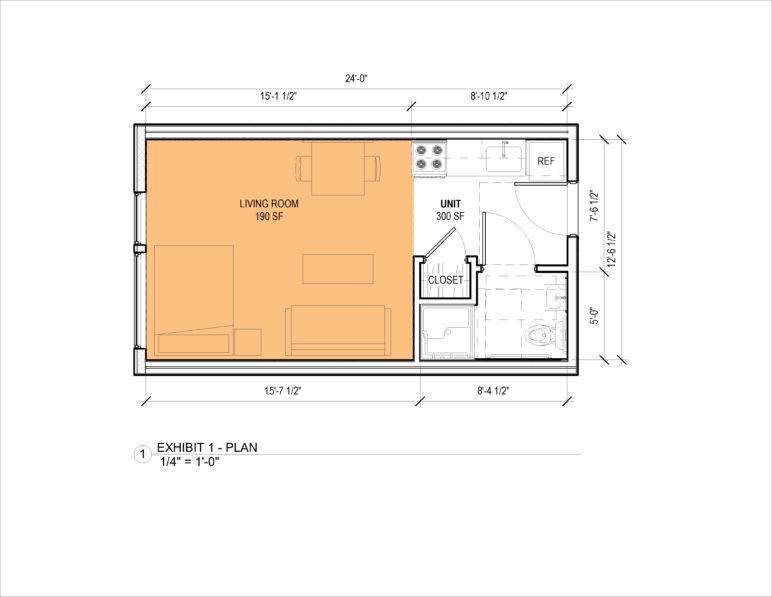

Here is what a typical 300-square-foot studio apartment plan looks like (see Figure 1). It features a 190-square-foot living room, which accommodates a bed, a couch, and a small dining area. Additionally, there’s a compact kitchen, a storage closet, and a bathroom.

If you’re a developer aiming to provide the most homes at the lowest cost, your goal is to reduce the unit size to get the most units possible into a floorplate. Under current rules, you can’t reduce the living room below 190 square feet, and accessibility codes mandate a minimum bathroom size, typically 5 feet by 8 feet. To squeeze in more units per floor, the only option is to shrink the kitchen and storage space to the bare minimum. Here is a plan of what that looks like.

Figure 1: A mandated 190-square-foot living room in a 300-square-foot home reduces kitchen and storage spaces to their absolute minimums. Image by Neiman Taber Architects.

Status evolved: More livability, less living room

Now let’s try a different approach. From a livability perspective, empty floor space is probably the least important feature that a person needs in their home.

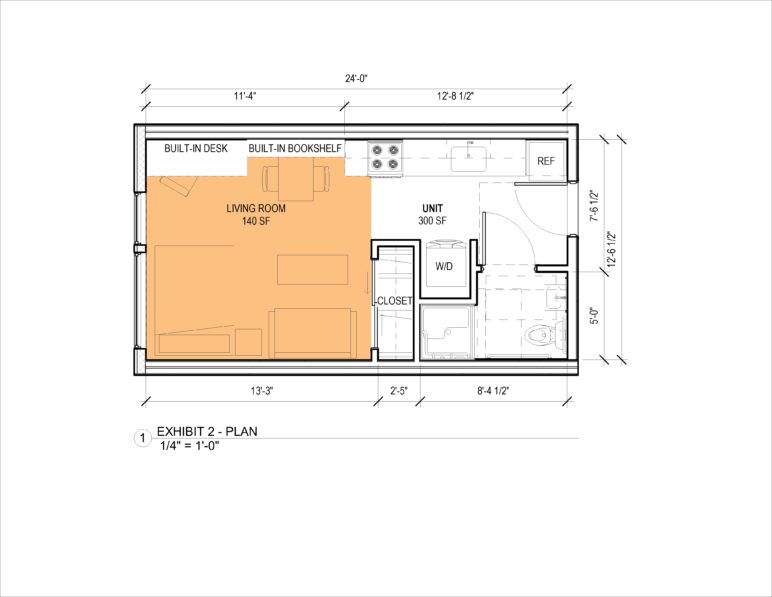

In this redesigned plan of the same unit, we’ve increased the kitchen size, providing more countertop workspace, additional storage and cabinets, a washer-dryer unit, a desk, and bookshelves. There’s still enough room for furniture, but by trading some living room area for more practical built-in features, we’ve created a significantly more comfortable home. And the total unit size is still 300 square feet.

Figure 2: A revised design with a 140-square-foot living room in a 300-square-foot home increases kitchen counter space and adds more storage space, built-in furniture, and even a washer-dryer. Image by Neiman Taber Architects.

Use the slider below to compare the two designs: the first with its 190-square-foot living room and the second with its 140-square-foot living room—and added kitchen counter space, storage space, built-in furniture, and even a washer-dryer. Which would you prefer to live in?

These two plans demonstrate a simple point: If you’re trying to design a building code to make a small unit more livable, forcing the living room to be larger is the wrong approach. Unfortunately, this is exactly what the IBC does.

The origins of the IBC’s 190-square-foot living room mandate

It’s worth a moment to discuss where the requirement for a 190-square-foot living room comes from. It’s not a universally accepted number. Until the 2018 IBC code update, the minimum standard for a living room was 220 square feet. Seattle’s SEDU standards allow for a 120- to 150-square-foot living room, depending on how you measure it. The IBC also allows congregate housing units—i.e., where residents have a private bedroom but share things like a kitchen, dining room, and other common spaces—with living spaces as small as 70 square feet. These are all forms of permanent housing meant for use by the general public, yet the size requirements vary widely.

A skeptical observer might wonder if these square footage requirements have any empirical basis or are merely arbitrary. A review of historical codes would prove the skeptic right. The Uniform Building Code, the predecessor to the IBC we use today, was first published in 1927. About two decades later in 1946, it introduced minimum room sizes, including an 80-square-foot living room. In 1964 the requirement grew to 90 square feet. In 1973, the requirement suddenly more than doubled to 220 square feet.

The square footage minimums do not stem from a long tradition nor any particular health or safety principle. The fact that today’s standard arrived suddenly in the early 1970s likely has more to do with urban politics of the day. At that time, most American cities were in decline, losing their population and tax base to the suburbs and struggling with high crimes rates. In reaction, many cities enacted policies aimed at getting rid of small, low-cost housing types like SROs where poor people lived.

Another way: Public health-informed priorities and sizing

Public health experts have long acknowledged that the built environment heavily impacts human health. The National Healthy Housing Standard (NHHS), developed by public health professionals, serves as a tool for planners, elected officials, and policymakers to design regulations for housing that are based on the public health literature.2

So what does the NHHS standard recommend for minimum living room sizes? A mere 70 square feet. However, this is not the end of the story. While the IBC focuses primarily on living room size, the NHHS gives more attention to subjects such as cleanliness, adequate storage, and functional food preparation.

For example, the NHHS stipulates the need for a kitchen with both a range top and oven, a refrigerator and a freezer, and a designated space for utensils and cooking tools. It also requires a kitchen to have a washable backsplash and cleanable floors. In contrast, the IBC remains mostly silent on these matters, requiring only a microwave oven, a sink, and a mini-fridge.

Another example: The NHHS mandates the use of low-pile carpets, non-absorbent flooring, low-VOC finishes, and other requirements aimed at providing cleanable surfaces and healthy indoor air quality. The IBC is silent on these matters.

In general, if we look to the IBC as a guide for designing micro-homes, we end up with larger and more expensive housing units than necessary, often lacking important livability features. In contrast, the NHHS permits smaller and more efficient homes but demands other essential amenities for livability, well-being, and sanitation.

What would a better micro-home look like?

At this point we’ve established a few things.

- The current standards are somewhat arbitrary.

- Living room size is not a reliable measure of livability.

- A better standard would focus much less on unit size and more on design elements that support healthy lifestyles.

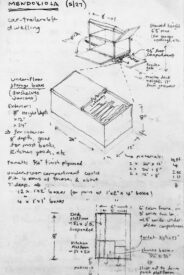

Clearly, we can build humane, quality housing smaller than what the IBC code allows today, but the question remains: how small is too small? Below are floor plans for micro-homes with living rooms of 120, 95, and 70 square feet in 250-, 220-, and 200-square foot units respectively—and plenty of space for living well in each.

The 120 in a 250: A Seattle SEDU-compliant option

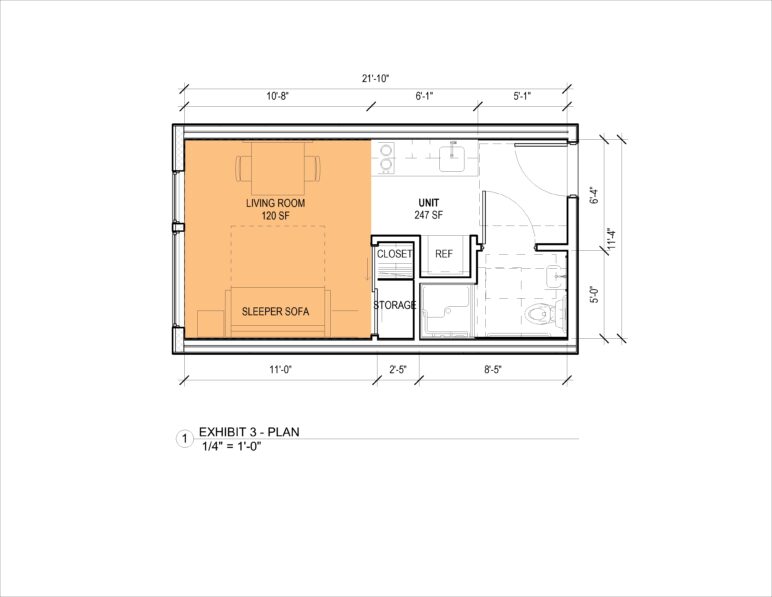

Figure 3: A 250-square-foot studio that is Seattle SEDU-compliant. With a 120-square-foot living room, it can’t accommodate both a bed and couch in the living space. Image by the Neiman Taber Architects.

We’ll begin with a small studio along the lines of what Seattle allows for a Small Efficiency Dwelling Unit (SEDU). It complies with all of Seattle’s regulations, including some of the city’s idiosyncratic rules about countertop areas, storage configuration, and how to measure the living room.

In total, this SEDU measures 250 square feet. At this scale there is room for a basic kitchen, bathroom, and storage area, plus the minimum required 120-square-foot living room. The living room area can comfortably fit a dining room table plus one more large piece of furniture. Unlike the larger 300-square-foot studio in Figures 1 and 2, we don’t have enough space for both a couch and a bed, so we opted for a convertible sofa that can serve both purposes.

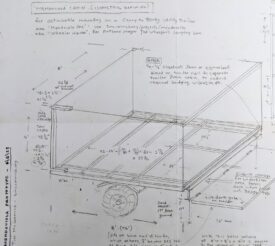

The 90 in a 220: More kitchen and storage, plus a washer-dryer

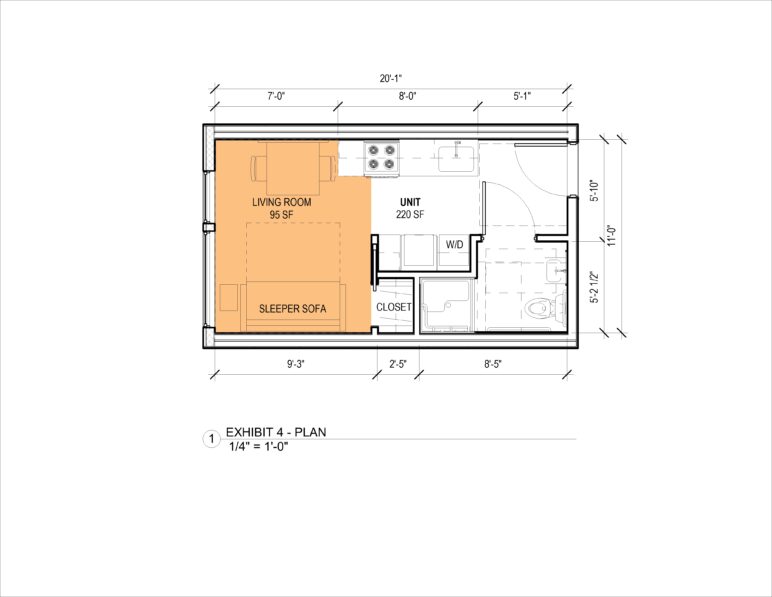

Figure 4: A 220-square-foot SEDU variation, with a smaller living room and more kitchen space, storage, and even a washer-dryer. It complies with Seattle’s SEDU rules for total square footage but not living room square footage. Image by Neiman Taber Architects.

This design is a variation on the SEDU. It meets the city’s minimum total square footage for a Seattle SEDU, but it dispenses with the city’s living room size minimum. (The design also meets the minimum requirement for a small studio under a similar program in San Francisco.)

This is the scale of unit that was typical for SEDUs in Seattle before 2016, when building officials enacted a series of code interpretations that changed the way that habitable space is measured, requiring a larger living room area. Compared to the slightly larger unit and living room above, here we can still fit the same suite of furniture, but also a larger kitchen, a more useful storage area, and a washer-dryer. For comparison, this living room is about 95 square feet, so losing just less than a quarter of the living room space of the prior design.

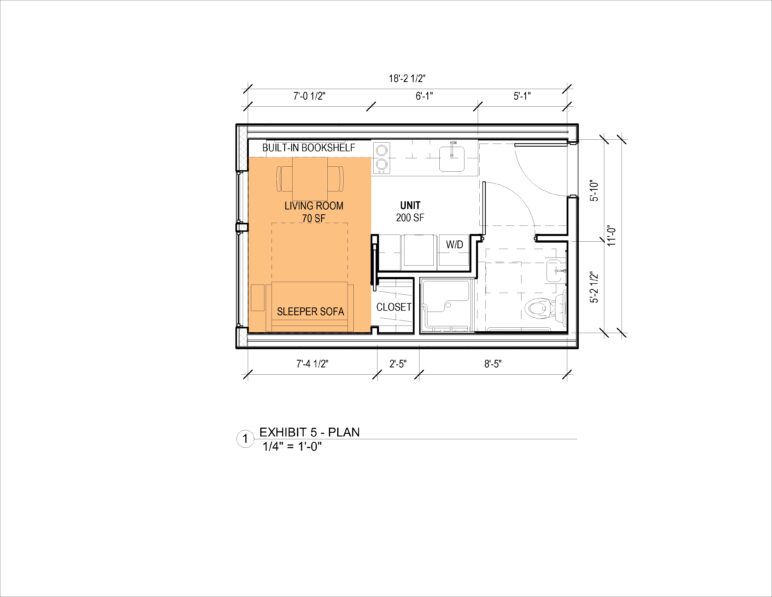

The 70 in a 200: NHHS-approved, with handy built-ins, more kitchen and storage, plus washer-dryer

Figure 5: A 200-square-foot micro-home with a 70-square-foot living room boasts more kitchen and storage space, plus a handy built-in bookshelf, all compliant with the National Healthy Housing Standard. Image by Neiman Taber Architects.

The NHHS says that the minimum habitable space for a dwelling unit’s living room is 70 square feet. So let’s look at what that accomplishes in terms of the overall unit size and layout

We’ve kept a similar suite of amenities in the kitchen and bathroom as the prior design, meaning more kitchen countertop and storage, plus a washer-dryer. And with only 70 square feet of living room area, there’s still enough room for a sleeper sofa and dining table, plus we’ve increased the functional use of the room with a built-in bookshelf. It’s cozier than the versions with larger living rooms but still a functional home that serves a person’s basic needs well and comfortably. The overall size of this unit comes out to just over 200 square feet.

Policymakers should prioritize livability and an abundance of housing options

The IBC standards that we use today to regulate small unit housing are clearly counterproductive. They prohibit the creation of smaller, more affordable units that could help put a dent in our housing crisis, and they prioritize space over livability, functionality, and cleanliness.

If lawmakers have concerns about the livability of small units, they should look to the standards of the NHHS for guidance. Current living room requirements have no empirical basis; they make our housing less plentiful and more expensive; and contrary to their intent, they result in less functional housing units with fewer amenities. It’s possible to make desirable homes for people far smaller than the size required by the IBC. The options we illustrated work well down to about 200 square feet.

It’s possible to go even smaller. In our congregate housing projects, units can be as small as 120-150 square feet when the building also provides common kitchen, dining, and other amenities that supplement the private units. This illustrates a larger point, which is that beyond the basics, the specific features of the private unit are often less important than the quality of the environment in which they are situated.

Likewise, micro-homes work best in neighborhoods that provide residents with easy access to amenities such as parks, grocery stores, libraries, schools, restaurants, retail, and services.

Policymakers can unlock housing opportunities for thousands more people in Washington and across Cascadia by amending our state building code to reduce the minimum living room size, allowing builders throughout Washington to create plentiful, affordable homes for their communities.